Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

We have no blueprints to guide us. We have no precedents to show us the way. There are no panaceas, no pat formulas to meet these problems. But we are meeting them, and I'm confident that the results will be inspiring when they can be told.

Listen to a podcast about this story

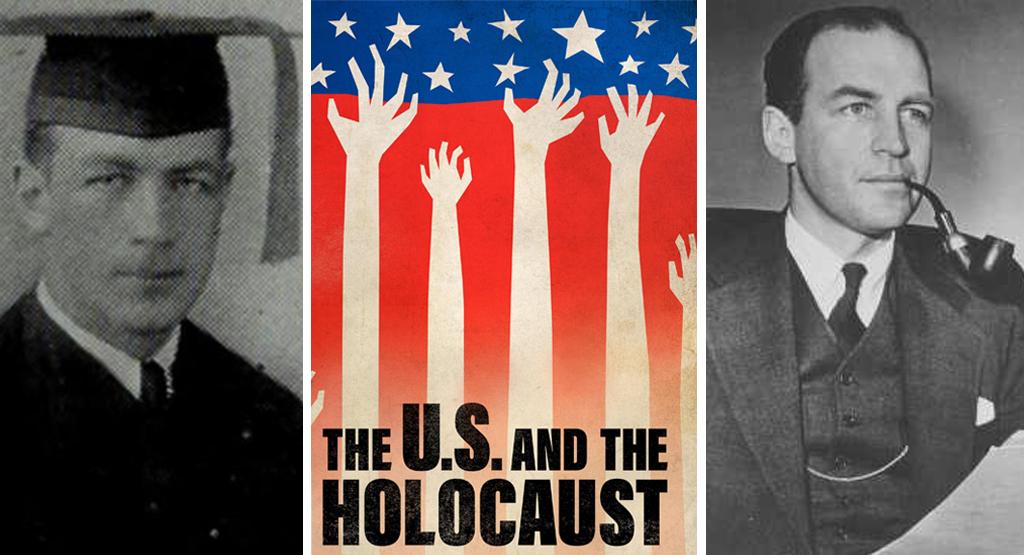

The U.S. and the Holocaust is now available to watch for free on PBS.org. Creighton alumnus John Pehle, BA’30, is featured prominently in the third and final part of the series.

* * *

By Micah Mertes

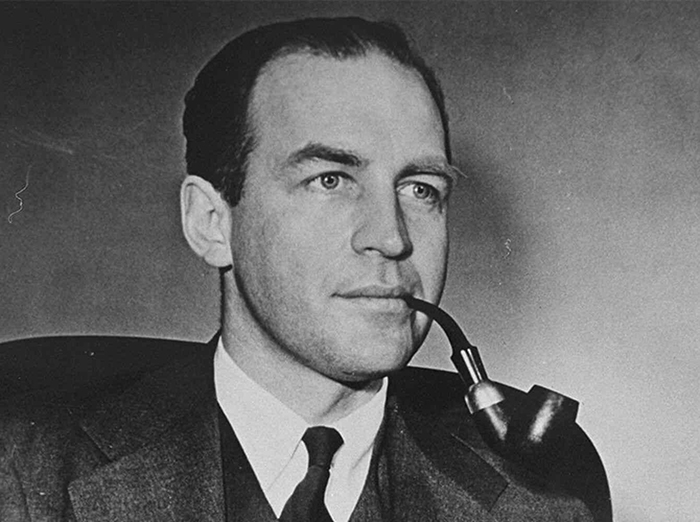

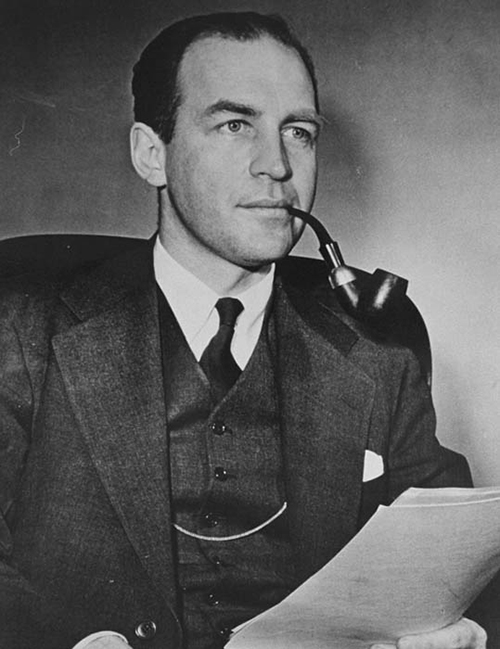

He was one of the most consequential individuals ever to graduate from Creighton University, though few know his name.

But more than 20 years since his death, John Pehle, BA'30, is a key figure in the new three-part PBS documentary series The U.S. and the Holocaust, directed by Ken Burns and his longtime creative partners Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein.

The series examines the American government and press’ response to the Nazis’ mass murder of European Jews. Burns’ thesis — backed by the exhaustive detail that marks all his work — is that while America did much good during the war, it did far less than it could have to rescue the Jews from Hitler’s regime.

Pehle himself — a man who helped save tens of thousands, perhaps even hundreds of thousands of lives — later said America’s efforts to help the Jews were woefully inadequate.

A son of German immigrants, Pehle (pronounced PAY-ly) was born in Minneapolis and grew up in Omaha near 42nd and Center Streets. He went to Central High School, then Creighton. To pay his room and board, he worked nights at the Dundee Theatre.

In 1930, he graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences with a philosophy degree and for a time attended Creighton’s School of Law before switching to Yale. Shortly after receiving his law degree, he went to work for the U.S. Treasury Department.

By the time America had entered the war, Pehle had ascended the ranks of the Treasury to become the head of Foreign Funds Control. In the summer of 1943, Pehle’s office received a license request from the World Jewish Congress to fund relief for the Jews in France and Romania.

The Treasury typically prohibited financial arrangements within enemy territory, but Pehle granted the license. He soon found his efforts stalled by the State Department.

“The State Department was quite negative,” Pehle says in an archival interview featured in The U.S. and the Holocaust. “It worried about the possibility of funds falling into the hands of the Germans. However, we went back and decided that we could put safeguards in the procedures so that no foreign exchange would come to the Germans.”

Knowing that each day of delay cost countless lives, Pehle and other Treasury officials dug into the reasons behind the State Department’s inaction. What they found, they would later report, wasn’t merely bureaucratic inertia but deliberate obstruction.

The obstruction didn’t stop at the stalling of relief aid. Pehle’s investigation also uncovered a series of cables from early 1943 showing the State Department attempting to keep information of Hitler’s mass murder of the Jews from reaching the United States.

The State Department’s suppression of both facts and funds had come at a time when much of America was well aware that Hitler was carrying out his plan to kill all of Europe’s Jews. But awareness didn’t mean emphasis, let alone action.

Near the end of 1942, World Jewish Congress president Rabbi Stephen Wise released a report, also initially suppressed by the State Department, that 2 million Jews had already been murdered. The New York Times ran an article … on page 10.

A short while later, the United States and its United Nations allies formally condemned the Nazi government. Congress introduced a bill known as the “Rescue Resolution,” which recommended action to save the surviving Jews of Europe. The bill passed in the Senate but not the House. The State Department, meanwhile, continued its failure to act.

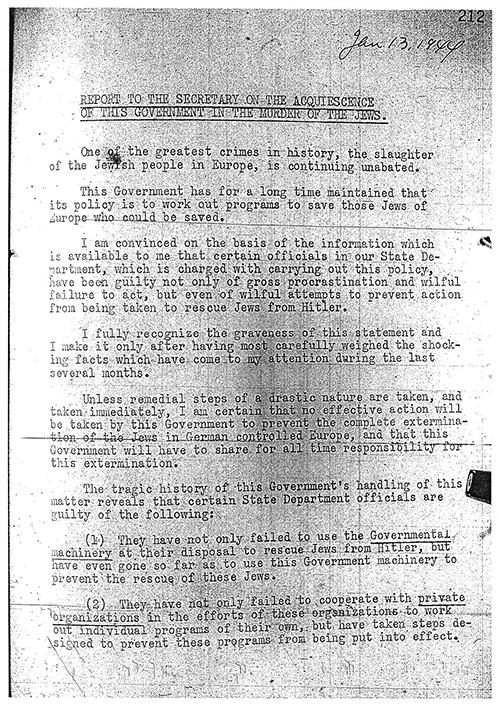

By the end of 1943, John Pehle had had enough. He and two other senior officials in the Treasury Department penned and presented a scathing 18-page report to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. The report, written in the first person, was titled: “Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews.” (You can read the full text here.) The report’s outraged tone didn’t stop at its name. It began:

“One of the greatest crimes in history, the slaughter of the Jewish people in Europe, is continuing unabated.

“This Government has for a long time maintained that its policy is to work out programs to serve those Jews of Europe who could be saved.

“I am convinced on the basis of the information which is available to me that certain officials in our State Department, which is charged with carrying out this policy, have been guilty not only of gross procrastination and willful failure to act, but even of willful attempts to prevent action from being taken to rescue Jews from Hitler.

“I fully recognize the graveness of this statement, and I make it only after having most carefully weighed the shocking facts which have come to my attention during the last several months.

“Unless remedial steps of a drastic nature are taken, and taken immediately, I am certain that no effective action will be taken by this government to prevent the complete extermination of the Jews in German-controlled Europe, and that this Government will have to share for all time responsibility for this extermination.”

The report then accused State Department officials of obstruction, deceit and cover-up. Shortly after receiving the report, Secretary Morgenthau — the only Jewish member of Roosevelt’s cabinet — arranged a meeting with the President.

On January 13, 1944, Pehle and Morgenthau presented the report to Roosevelt. They also came to the meeting with a drafted executive order to create a new government agency tasked with “the immediate rescue and relief of the Jews of Europe and other victims of enemy persecution.”

One week later, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9417 establishing the War Refugee Board. The order allotted $1 million to the agency. All other funding for rescue and relief efforts came from private sources. Pehle was appointed as the agency’s executive director. He was only 34.

In an interview shortly after his appointment, Pehle said:

“I am aware that we face perhaps the greatest humanitarian task of all time. I am aware of the urgency of that task. We must thwart the Nazi program swiftly and decisively.

“We have no blueprints to guide us. We have no precedents to show us the way. There are no panaceas, no pat formulas to meet these problems. But we are meeting them, and I am confident that the results will be inspiring when they can be told.”

The task of the War Refugee Board is, he said, “the simple, honest job of saving the lives of people who are inside Hitler’s Germany and in imminent danger of death.”

Pehle and his team of self-professed “red-tape cutters” got to work fast, navigating inter-agency conflicts to rescue as many surviving Jews as they could.

The board streamlined humanitarian aid to Europe. It released detailed reports of the horrors in the Nazi death camps Auschwitz and Birkenau. It financed evacuation efforts and established refugee camps. It unfroze funds, issued visas, created false ID papers and reportedly even laundered money and paid bribes to Nazi sympathizers via covert agents. Whatever it took.

Organizations and individuals from all across the country offered money and shelter to the War Refugee Board’s cause. One Colorado rancher sent Pehle a $100 donation directly, along with an offer to provide homes on his ranch for five Jewish refugee families. “I will see,” the rancher wrote Pehle, “that they are sheltered under the principles of the four freedoms.”

The timing of the board’s creation was most significant for Hungary, where the Nazi regime was just a few months away from deporting Jews to concentration camps.

After the war and shortly before its dissolution in 1945, the War Refugee Board estimated it had saved the lives of tens of thousands of Jews. Some historians have estimated the number at more than 200,000.

But as noted in The U.S. and the Holocaust, an estimated 5 million Jews had been executed by the time American rescue operations had begun.

Even Pehle — a man whose whistleblowing and leadership had played a critical role in every life saved — considered the War Refugee Board’s efforts severely lacking.

“What we did was little enough,” he later said. “It was late. Late and little, I would say. Looking back at the board, the resources available were too small to deal effectively with the problem.

“But we were able to change the policy of the United States, and we were able to help the private agencies, and we were able to change the moral position of the United States in this area.”

After the war, Pehle entered private practice to work as a tax attorney. He later served as a partner of the international firm of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius. He died of cancer in 1999.

In 2006, he was posthumously awarded a congressional gold medal “in recognition of his contributions to the nation in helping rescue Jews and other minorities from the Holocaust during World War II.”

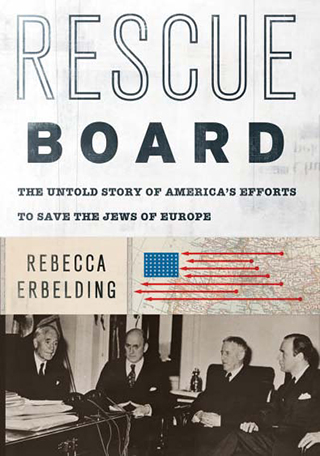

In the 2010s, a series of books about the War Refugee Board — most notably Rebecca Erbelding’s Rescue Board: The Untold Story of America's Efforts to Save the Jews of Europe — brought some recognition to Pehle and others. But, without question, Burns’ new documentary series is the largest platform this story has received thus far.

The U.S. and the Holocaust presents few triumphs, its focus primarily on all America didn’t do to rescue the Jews of Europe.

But the documentary also sheds much-needed light on figures like Pehle — a man who believed that a person can be a source for good in the world. A man who helped save tens of thousands of lives, yet spent the rest of his own lamenting he hadn’t saved more.