Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

I know more than ever that the crash and our return was destiny.

By Micah Mertes

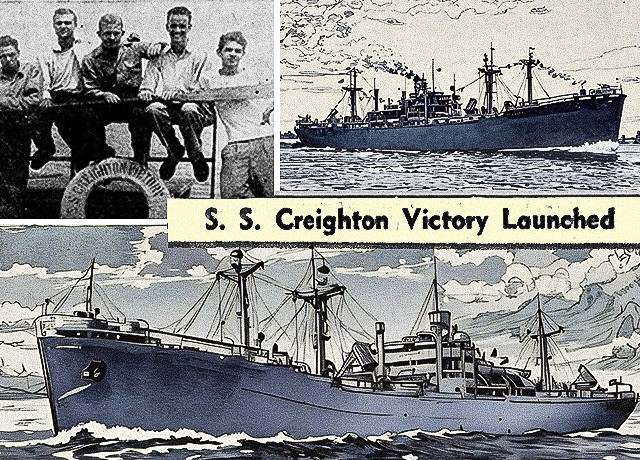

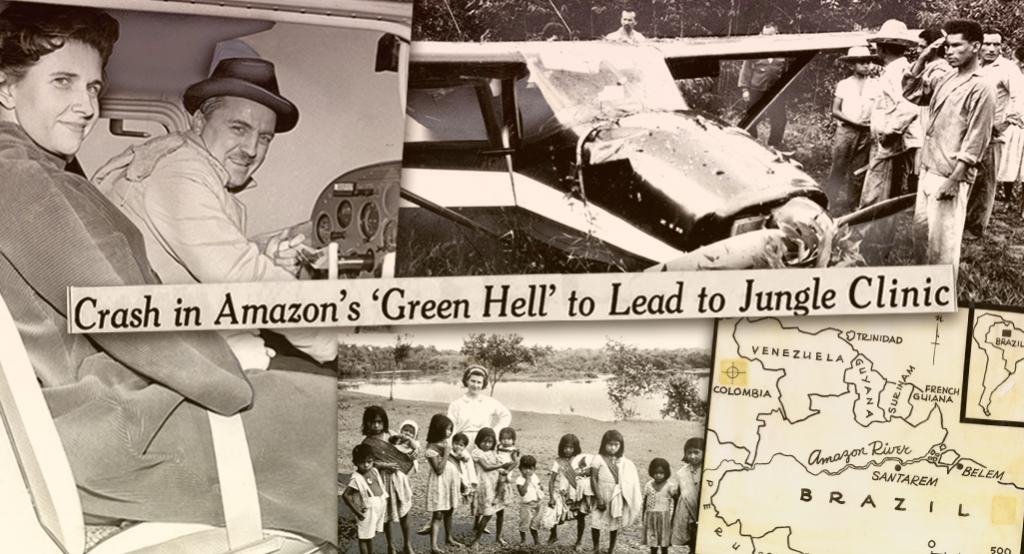

Sixty years ago, in the spring of 1965, Creighton couple James Maly, MD’46, and Jan McDermet Maly, SJN’48, were flying across South America when a run of bad luck forced them to crash-land their single-engine plane in the Amazon.

Stranded deep in the Brazilian jungle, hundreds of miles from civilization, a “green hell” in every direction, the Malys and six others faced starvation, insect bites and life-threatening injuries.

The crash was, the Malys later said, a gift from God.

* * *

James and Jan Maly were known in Nebraska as “the Flying Doctor and Nurse.”

The year before the couple crashed in the Amazon, the Omaha World-Herald wrote a front-page feature on them. The Malys lived in Fullerton, Nebraska, 125 miles west of Omaha, where James was the surrounding Nance County’s only physician.

But the people of Fullerton weren’t limited to the town’s 18-bed hospital. The Malys had their own air ambulance, a Cessna 210 that could deliver patients to Omaha emergency rooms.

James had learned to fly after serving as a surgeon for an Air Force rescue unit in Alaska. He had taught Jan how to fly, as well, so she could take the controls while he needed to aid patients en route to the ER.

After a 35-minute flight to Eppley Airfield (where James had installed lights for his night landings), the Malys would transfer patients to a waiting ambulance, where they would be taken to emergency or specialist care at St. Joseph’s Hospital or elsewhere.

James said the rural county’s fast access to Omaha specialists and facilities had saved many lives that year alone, including a 12-year-old gunshot victim and a 19-year-old woman who nearly froze to death after walking four miles in 30-below-zero temps after her car broke down.

“The airplane is a Godsend to a country doctor and his patients,” James Maly told The World-Herald in 1964. “It brings us as close to the major medical facilities as a big-city patient who has to buck crosstown traffic to get to the same place.

“And I’m convinced it’s 10 times safer than driving on the Omaha highways!”

* * *

The Malys weren’t content to fly the skies of Nebraska alone. They sought more unfamiliar horizons.

In the spring of 1965, they embarked on a several-week vacation across the length and breadth of South America. Their friends — the Stalzers of Chicago — joined them in the Malys’ Cessna, while another flying physician, Willaford McCall, flew three of his friends in his own single-engine aircraft.

After meeting up in Mexico, the two planes flew through Panama and down the South American west coast. From Chile, they crossed the Andes mountains, then on to Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and Brasilia. On March 28, they set off from Brasilia to the city of Manaus, a 1,250-mile flight over the jungles of Brazil.

Everything went wrong. (Or, as the Malys later said, everything went right.)

The eight Americans on both planes were met with bad weather, equipment malfunction, human error, miscommunication between the pilots and airport officials, an erroneous flight plan and an inoperative radio beacon.

With all communication links broken, hundreds of miles deep in the Amazon, both planes started to run out of fuel. Maly and McCall turned toward the river, hoping to reach a known emergency field. But after more than 8 hours of flying through a wall of low-hanging storms, even the planes’ emergency tanks had run dry.

They planned to ditch the planes in the river, Maly later said, “but then the hand of destiny” took hold.

They came upon a clearing along the river, the start of a planned airstrip. The trees and logs hadn’t yet been removed, but it was still a better option than they could have hoped for.

When he brought his plane down, Maly hit a half-hidden log that buckled the aircraft’s undercarriage and drove the pedals into his legs, crushing them at the ankles. McCall’s plane crash-landed nearby.

Somehow, no one died. Maly’s legs were shattered, one passenger’s arm was broken, and another fractured his back, but everyone else suffered only minor cuts and bruises.

But the party knew their chances of survival didn’t get much better from there. They were lost in the jungle and, due to a reporting error, no one knew to come looking for them. They had to contend with not only their injuries but starvation, deadly wildlife and the possibility of headhunting tribes they knew lived near the crash site.

Yet, once again, somehow, no one died.

* * *

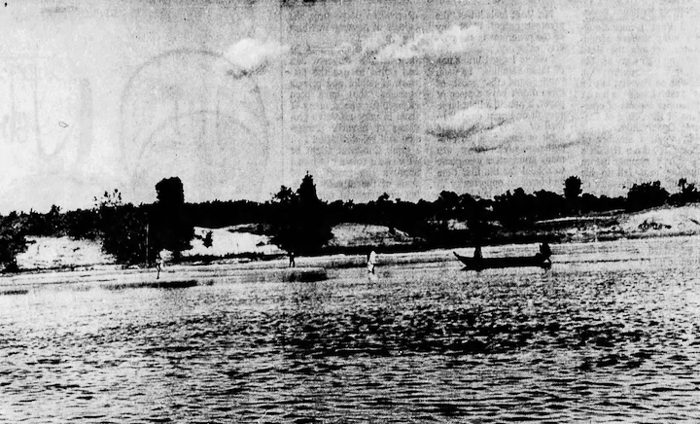

They tended their wounds the best they could and used jungle debris to make splints for those with broken bones. They were figuring out what to do next when a group of people came through the clearing and greeted them. They were members of the Mundurucu tribe, and they would serve as the marooned party’s salvation.

As it turned out, the Americans had crashed 35 miles northwest of a tiny Franciscan mission called Cururu, where Father Marquard Paterek, OFM, of Cleveland, two Bavarian priests and seven nuns served and ministered to the Mundurucu and other tribes in the region.

The mission was more than 500 miles from the nearest doctor and cut off from the outside world for all but two weeks per year, when planes or boats delivered the mission’s supplies.

To reach the sanctuary of the mission, the Mundurucu took the Americans through the jungle to a tributary launch site and down the river in dugout canoes. “How they got us to the mission, I’ll never know,” Maly later said. The journey just didn’t seem possible.

Other members of the tribe, meanwhile, traveled four days downriver to a Brazilian Air Force landing strip to get word of the downed plane to the outside world. Over the next several days in Cururu, Fr. Paterek and his team cared for Maly and the others while they awaited rescue.

Two weeks later, the Malys were back in Omaha, where James was taken to Bergan Mercy Hospital to undergo surgery on his broken legs. The operation was a success, and two weeks later, he was back at work as Fullerton’s only country doctor, performing surgeries from his wheelchair. He “kicked the old wheelchair” a few months later and was back to flying shortly after that.

The daring crash-landing and rescue made the front pages of newspapers all over the country. Despite everything, Maly told the press, he had every intention of not only flying again but flying across the Amazon jungle again.

“I have a debt to repay and a destiny to meet,” Maly said. “Yes, sir, I am convinced that crash was destiny.

“The good Lord knew that the mission needed medical help. The misunderstandings at the Brasilia airport, the weather and everything else that day were part of it. Then, as we flew over the jungle, the Lord looked down at us and said, ‘Hmmm, three doctors. Just what we need. Just a minute, boys.’ Then our gas ran out.”

* * *

Before the crash, Fr. Marquard Paterek, leader of the Cururu mission for decades, prayed for help. In addition to ministering to the 2,000-member Mundurucu and other tribes, the mission could help meet most of the native peoples’ needs. Medical care was the major exception.

Fr. Paterek and the sisters knew enough to help the Mundurucu to some degree, but they lacked the skill and resources to address such diseases as tuberculosis, leprosy and intestinal parasites. They needed a proper clinic.

The priest’s prayers were answered, he later said, when God brought down two planes of doctors and nurses within 35 miles of the mission.

“My wife and I have been obsessed since our safe return to help establish a clinic for those wonderful people,” Maly said in late 1965.

The couple and the other members of their rescued party formed the nonprofit Cururu Medical Mission Society to establish a clinic at the mission. Thanks in part to the wide-ranging media coverage the story received, clinics, supply houses and drug companies lined up to donate services, medicine, equipment and funds to the cause.

Maly’s Nance County patients grew nervous that the area’s only doctor would be leaving again. “I’ve had calls from expectant mothers telling me I couldn’t go until their babies came and another call from a sweet old lady who said I couldn’t go until I’ve given her her flu shot,” Maly said in 1965. (Two Omaha doctors watched over Maly’s practice while he was abroad.)

In July 1966, the Malys launched Operation Helping Hand, leading a team of physicians, nurses and lab techs to the Cururu mission to establish a clinic. More than 40 healthcare professionals volunteered to go, though there weren’t enough seats to take everyone. A follow-up expedition was planned for later that fall. The Malys once again flew their own single-engine plane several thousand miles from Fullerton to the jungle.

The team arranged the delivery of more than a ton of medical supplies, equipment and medicine donated by various American institutions, including Creighton University. The crew spent eight weeks at the mission performing surgeries, treating the sick, establishing the clinic and delivering a crash course in medical care to the priests and sisters.

The operation focused on a number of ailments: the prevention of parasites, treatment of tuberculosis, vaccinations for diphtheria, tetanus, measles, smallpox and whooping cough. The Malys also traveled by river to reach outlying members of the tribes.

James Maly extended his Nance County air ambulance service to the Mundurucu. During his eight-week stay, he flew the 1,000-mile roundtrip to Santarem several times to deliver various patients to the town’s clinic. He also flew lepers to a clinic in Belem, a 2,000-mile roundtrip from Cururu.

Life-saving medical transportation wasn’t the only role Maly’s plane served. It was also often loaded to capacity with medicine, mail, supplies and, on a few occasions, several cases of beer.

By the time the Malys left Cururu, they had delivered an estimated 2,800 vaccines, treated everything from ulcers to worms to malaria, assisted with research on area diseases and trained the mission’s seven sisters in basic first aid and use of the medical supplies they would leave behind.

“I know more than ever that the crash and our return was destiny,” Maly told The World-Herald upon his return to Fullerton. “Maybe we have repaid some of the kindness and care. But there is so much more to be done. We’ve just scratched the surface. Yes, we’ll be back to do what we can.”

* * *

James and Jan Maly returned to Cururu for four to six weeks every year from 1967 to 1971. They stopped flying to the mission only when the operation’s cost and complications with the Brazilian government became prohibitive.

In 1967, Creighton awarded James the Alumni Achievement Citation for his “devoted labors to improve the well-being of his fellow men at home and in other lands.” He later received a special Humanitarian Award from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska.

In 1981, the whole town of Fullerton and the surrounding community came together to celebrate Doc Maly’s decades of service with an Appreciation Day event. Maly was strongly opposed to receiving the honor, which he thought felt too much like a farewell. (“I’m not about to retire. I’m going to be a country doctor until I die.”) But Jan convinced him to let his longtime patients give their thanks. More than 700 people showed up.

Less than a year later, Maly died from a heart attack at the age of 58. Up to the day of this death, he was still caring for everyone in Fullerton, performing surgeries and often seeing as many as 100 patients a day.

Jan Maly lived for another 30 years, passing away at the age of 84 in 2012.

Friends, family and former patients said that whether it was in rural Nebraska or the Amazon jungle, Creighton’s flying physician and nurse repaid their debt and fulfilled their destiny wherever they landed.

* * *

Sources for this feature:

Omaha World-Herald archives, particularly the articles of longtime writer Tom Allan

Tom Allan's book — To Bucktail and Back: A Million Miles of Memories