Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

I’m not bragging or anything, but I’m pretty ingenious.

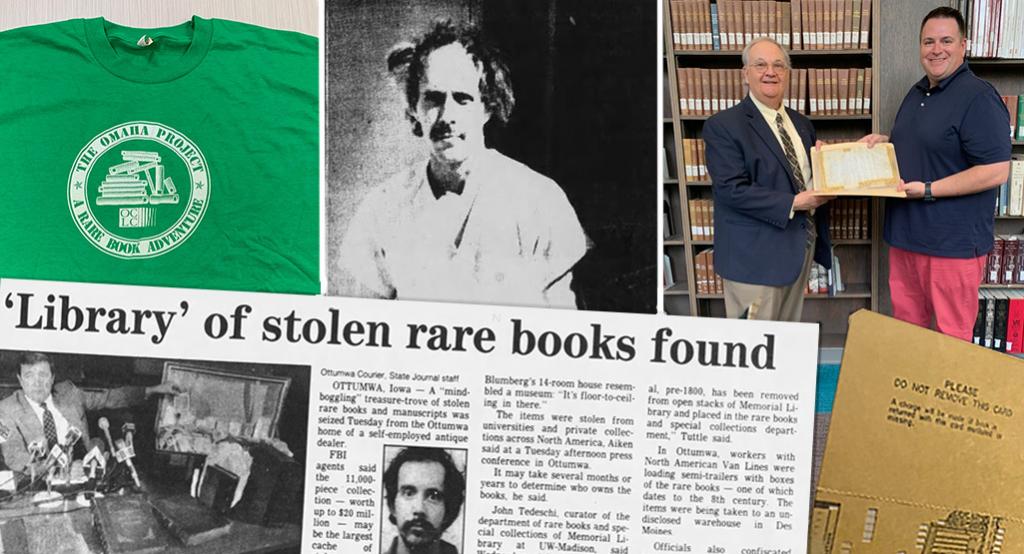

In the story of the Guinness World Records-certified most prolific book thief in world history, Creighton University just keeps popping up. First, a Creighton alumna aided the detective trying to catch the thief. Then, a group of Creighton librarians worked with the FBI to return thousands of stolen books to their rightful homes.

Here’s the tale of the Iowa man who swiped somewhere between 23,000 and 26,000 rare books and papers from at least 300 university libraries across the U.S. (and Canada), and the FBI investigation (code name: “The Omaha Project”) that turned 10 Creighton librarians into a makeshift team of academic detectives working out of a secret warehouse. It’s also the story of the recent Creighton class that led to a priceless manuscript making its journey back to an Oregon library more than 35 years after it was stolen.

You can read all about that class and the returned library items here. You can also check out a fantastic new online exhibit the students made about the book bandit and listen to our Weird Creighton History podcast interviews with Creighton archivist Pete Brink and assistant professor Trish Ross, PhD (all episodes located at the end of the article).

* * *

Stephen Blumberg, book bandit

By Micah Mertes

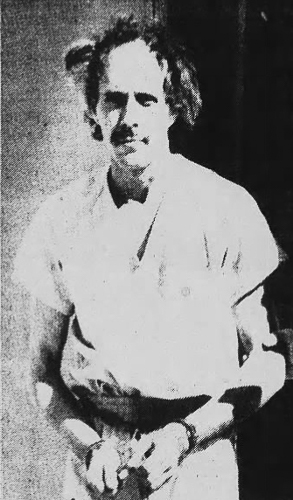

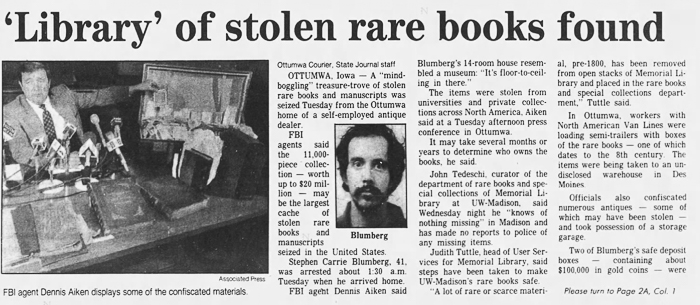

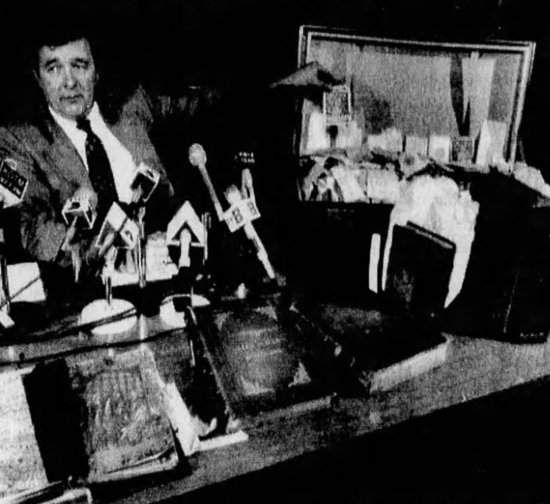

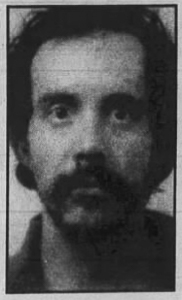

Late one night in March of 1990, in the town of Ottumwa, Iowa, FBI agents rolled up to the three-story, 17-room red brick home of Stephen Carrie Blumberg, a 41-year-old collector of books and antiques. Inside, they found more than 23,000 rare books and manuscripts.

Some of the books were valued at tens of thousands of dollars each: a first-edition copy of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a handprinted Bible from 1480, a first edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost, a 15th century world history that preceded Columbus’ discovery of the new world.

Book-packed shelves stretched from wall to wall and floor to 12-foot ceiling in most rooms. Even the bathrooms and closets. Shelves lined each side of the hallways, too, making for narrow passage. Despite the scale of the collection, it didn’t look like clutter. Books were organized neatly and (mostly) according to geography, since the bulk of the collection revolved around Blumberg’s interest in 19th century Americana.

A room on the northeast side of the house, for instance, represented New York and all its associated books. The top of the staircase was home to Ohio. Head west and one would arrive in California (this is the room where Blumberg slept, on a worn black leather chaise lounge). The second-floor bathroom served as an interstate cataloging area or sorts. It’s also where Blumberg got most of his reading done.

At the time the FBI discovered Blumberg’s library, it was one of the most impressive private collections of books in the U.S. And almost none of it belonged to him.

Over the previous 20 years, Blumberg had traveled the country many times over, stealing thousands of irreplaceable historical books and papers from an estimated 300 or more university libraries, along with museums and private collections.

He stole from Harvard University, Claremont College, the University of Oregon, the University of Southern California, Duke University, Washington State University, the University of Iowa, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and many others. (As far as anyone knows, Blumberg never stole anything from Creighton. Though he did threaten to pull a heist of Reinert-Alumni Memorial Library. More on that later.)

By the time the FBI caught Blumberg, he’d amassed a collection worth an estimated $20 million, with another estimate as high as $40 million. (Later, during his trial, the collection was negotiated down to $5.3 million, as the value of the collection determined the length of his prison sentence.) And mind you, this was in 1990 dollars. Whatever the collection’s true value, it would be worth more than twice as much today.

“Statistically, there has not been anyone who stole more books of such obviously high quality from more libraries than Stephen Blumberg,” said William Moffett, then the director of libraries at Oberlin College in Ohio. “For sheer quantity and total value, everyone is quite insignificant stacked up against what Stephen brought together.”

Guinness World Records seconded this claim, deeming Blumberg the “most prolific book thief” in world history. His closest rival is Guglielmo Libri, a 19th century academic who had a distinct advantage over Blumberg: He was the chief inspector of French libraries.

After Blumberg’s arrest, the FBI set about packing up the evidence. All 19 tons of it. It took 17 people two days and 879 packing boxes to get all the books and papers out of the house. (Here's a Des Moines local news video of them doing so.) It took two 40-foot tractor-trailers to haul it all to Omaha, where agents of the Iowa-Nebraska FBI headquarters had secured a secret warehouse to store and sort through the collection.

At the time of the case, W. Dennis Aiken was the assistant agent in charge of Omaha’s FBI headquarters. In 1990, he said: “What went through my mind was … how are we going to deal with the books?”

The FBI needed librarians. Here’s where Creighton comes in.

The Omaha Project

Around 40 people from 16 Nebraska libraries volunteered to assist the FBI’s investigation, including employees from such institutions as the College of Saint Mary, the University of Nebraska Medical Center and Iowa Western Community College.

Most of the libraries volunteered one or two people each. Creighton’s Reinert library provided 10. They ended up working about half the total volunteer hours dedicated to the effort. The University let them spend part of their workweek at the secret warehouse, essentially subsidizing a public service. Though some of the Creighton librarians also donated their own nights and weekends to the cause.

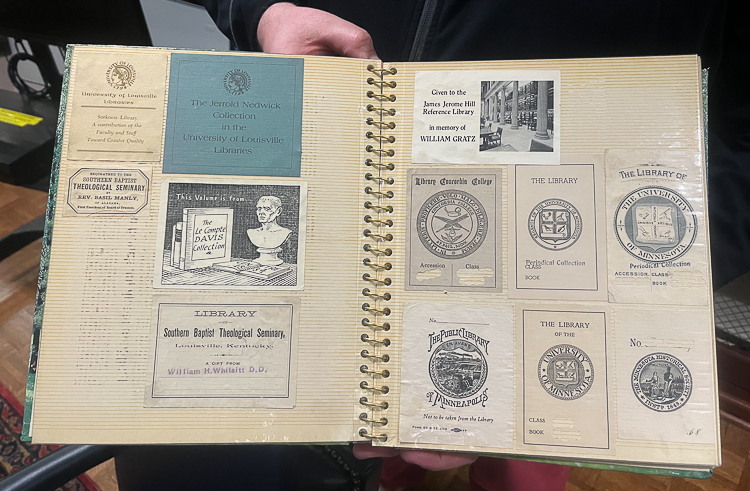

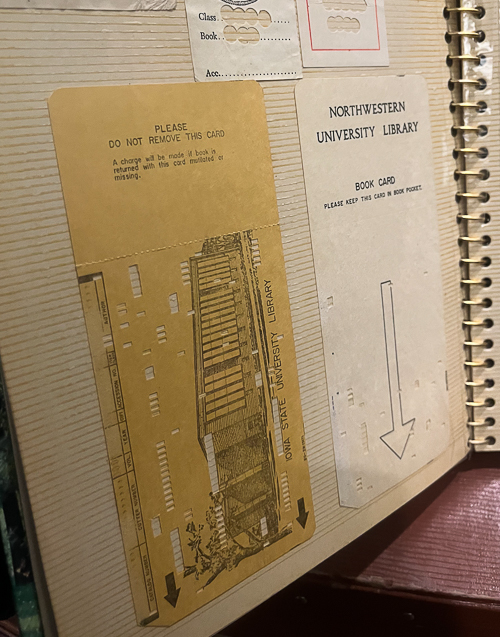

They had a tall task before them: more than 23,000 books and documents (perhaps not all stolen) that needed to go back to at least 300 university libraries. Making the job even more difficult, Blumberg had used razor blades and sandpaper to remove the identifying library stamps or bookplates from almost every item, in many cases writing or stamping his own personal mark into the pages. (He also used his tongue, sometimes spending hours licking off a single book’s library stickers and catalog pockets, to the point of making himself sick.)

Identifying the books’ provenance would turn the librarians into de facto detectives in a case the FBI had codenamed “The Omaha Project.”

One Creighton member of the Omaha Project was the Rev. Gregory Carlson, SJ, who employed his knowledge of foreign languages to help with the more difficult-to-understand titles.

“It was all incredibly secretive,” Fr. Carlson says now. “The FBI had security checks run on all of us. I wonder if they found out that my brother-in-law was in the CIA!”

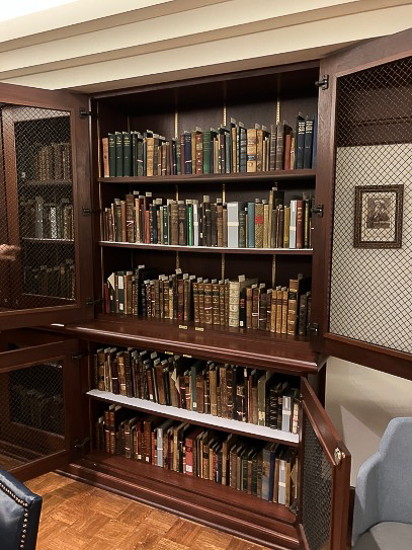

Fr. Carlson recalls his sense of awe upon entering the Omaha Project warehouse. (He doesn’t remember the address, but others recalled it being located somewhere along 84th Street.) Here was a collection of extremely rare books, so vast that it stretched across 3,500 feet of plain metal shelving (the shelves alone cost $11,000). The scope of it overwhelmed Fr. Carlson, who is something of a bibliomaniac himself. Over many years, he has amassed — legally! — a collection of more than 9,000 fable books and 4,000 fable-related objects (cataloged online by the Creighton Archives).

“I recognized in Blumberg a fellow book lover, though I hope in slightly different ways,” Fr. Carlson says, laughing. He couldn’t help but keep his eye out for fables while he and the librarians worked their way through the stolen books. He never found any.

Here’s how the Omaha Project worked: The FBI set up 10 terminals with access to the Online Computer Library Center, which at the time was the largest online bibliographic database in the world — 22 million items and 10,384 libraries. Using the terminals, the librarians combed through the books and papers, typed titles and descriptions into the terminals and attempted to match each item with its record.

They often had some idea of where to start. Because while Blumberg had removed the identifying markers from most of the books, he’d also kept the markers as trophies. In his collection, the FBI had found several scrapbooks full of bookplates and catalog pockets from many of the looted libraries.

(Another helpful asset in the investigation: Blumberg himself. While the Omaha Project was underway, Blumberg was out on bail awaiting his sentence. Seeking to gain some good will with the court, he continually came to the Omaha warehouse to help the librarians identify the stolen items’ proper homes. Blumberg was, of course, under the close supervision of FBI agents the whole time.)

Slowly but surely, the Omaha Project inventoried thousands of items. Focusing first on the collection’s most valuable books, volunteers were able to match much of the collection’s origins, contact the owners and eventually get most of the materials back to the right place. That summer of 1990, the FBI threw a thank-you party for Omaha Project volunteers at the Reinert library. Everyone got an “Omaha Project” T-shirt.

The FBI offered university libraries a long window to claim their items from the stolen collection. “Every institution we called, without exception, either had no idea what they lost or didn’t understand the extent of their losses,” FBI agent Aiken said at the time. “I couldn’t tell you how many people came in (to the warehouse) and said the very same thing: ‘I know the shelf this is supposed to be on.’”

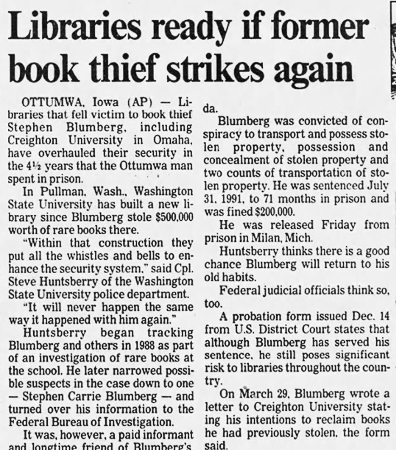

The Blumberg thefts ended up being a wakeup call for libraries and their near-universal lack of adequate security and inventory methods. It was later estimated that 95% of what Blumberg stole hadn’t even been missed.

Even after the Omaha Project’s exhaustive search, many of the books’ origins remained a mystery. By 1993, about 4,000 items were still unclaimed. As a token of gratitude for the Creighton librarians’ many hours on the case, the FBI gave those books to the Reinert library.

Creighton librarians archived the collection, then donated about 3,000 of the books to surrounding local libraries. Books and manuscripts thought to hold special value for Creighton were distributed between the stacks and the Rare Books Room. Some materials remained uncatalogued in boxes, awaiting rediscovery.

One unintended consequence of the FBI’s gift: Creighton was now on Blumberg’s radar. In March 1994, Blumberg wrote the University a letter from the federal penitentiary where he was being held. It read:

“I am writing this to notify you that I am intending on taking actions to regain books taken from my home in Ottumwa, Iowa, and subsequently given to your institution. None of the books found in my house could be claimed by your institution.

“My current circumstances have me constrained, whereby I can't effectively (reclaim my collection). But in the future, this I intend to do, and it is only fair to notify you.”

In response, Creighton stepped up security measures in the library’s Rare Books Room. Michael LaCroix, Reinert library director at the time, told the Creightonian: “We have every reason to expect Blumberg will show up.”

The Book Bandit’s 20-year crime spree

So who was Stephen Blumberg and why did he do what he did?

Just as relevant a question: How was he able to accomplish such a feat? That answer, at least, is a simple one. He had a lot of time on his hands because he didn’t have to work for a living.

Blumberg was the beneficiary of generational wealth, courtesy of a great-grandfather who’d started his fortune selling horses and provisions during World War I and by buying then-worthless land that later became valuable Twin Cities real estate. By the late 1960s, Blumberg was drawing a $72,000 annual income from a family trust. (Which came in handy when he wanted to buy a 17-room house, in a centrally convenient state, to store his library of more than 23,000 stolen books.)

Because he never wanted for money, Blumberg never stole for profit. He just really — really — liked collecting things. He once described himself as a “rescuer of the past.”

“Part of his obsession with books grew out of an obsession with old things,” says Trish Ross, PhD, an assistant professor at Creighton who taught an honors class about Blumberg this spring. “He seemed to imagine himself as a misplaced Victorian man who wanted to live in the 19th century. Most of his collection came from that time. He was fascinated by Americana and the American West.”

Blumberg’s obsession first emerged during his childhood in St. Paul, Minnesota. It started not with books but the fixtures of old Victorian houses — stained glass windows and ornate doorknobs. In his early years, he would pluck pieces off condemned houses. His hobby eventually escalated to breaking and entering, which led to the first of many arrests.

At some point, Blumberg started reading and collecting books about the antiques he was stealing, which opened up a whole new avenue of obsession — bibliokleptomania, an uncontrollable impulse to steal books. His first arrest relating to stolen library materials dates back to 1974, in Fort Lupton, Colorado. (It’s worth noting that this newfound love of old books didn’t impede his passion for stealing home fixtures, as well. At the time of his arrest, his Ottumwa home also contained about 50,000 antique brass doorknobs.)

Since money was no obstacle — especially since the thrifty Blumberg wore the same clothes all the time and opted to eat at soup kitchens instead of paying for his meals — he could hit the road (often with accomplices) for as much as six months at a time.

During these extended sprees, he would rent apartments in other states so he could linger as long as he wanted. He’d also rent local storage spaces to squirrel away his newly stolen books before taking them back to his private library. (He hadn’t purchased the house in Ottumwa until 1988, having previously lived in an old brick mansion in Minneapolis.)

Blumberg’s heists were targeted and meticulous. He sometimes spent weeks scouting a single location, getting a sense of the library security and triggering alarms to clock the guards’ response times. He became a proficient locksmith and lock-picker. Sometimes, he would steal the key to a rare book room from a custodian’s key ring, get a duplicate made and return the original before anyone knew it was gone.

Blumberg used his small, thin frame to get into the tightest of spots — crawling through ventilation ducts; climbing up metal grates to squeeze through the eight inches of space between grate and ceiling; shinnying up a dumbwaiter elevator shaft used to transport books.

One time, he later told reporters, his lithe (5-foot-9, 130-pound) frame saved his life. Late one night, he was climbing up a library’s elevator shaft to get to the special collections room on the seventh floor. He didn’t think anyone else was in the building. Then the elevator started moving. He darted into the nook of a small service platform to narrowly escape the elevator crushing him.

He could also, reportedly, scale buildings. Testifying at Blumberg’s trial, one of his accomplices referred to him as “Spiderman.” Others noted his talents as a master of disguise.

Blumberg would often befriend and recruit teenagers in his schemes. For libraries with lax security, he would find ways into the special collections, wait until the library closed, then throw books out a window to his accomplices.

One of Blumberg’s most effective methods was pretending to be someone else. One day, while visiting the University of Minnesota, Blumberg found the faculty identification card of a professor named Matthew McGue, with whom he shared some resemblance. From that day on, Blumberg identified himself as McGue at every library he visited, claiming to be doing research in whatever collection he intended to plunder. To further the ruse, he later forged a birth certificate and had five driver’s licenses made with McGue’s name.

Posing as a legitimate academic gave Blumberg greater access to the library buildings where special collections were kept, and he grew even more brazen. His exploits at Harvard University offer a prime example.

Using McGue’s faculty ID, Blumberg paid for a 90-day access pass for Harvard libraries. Day after day, he went to the libraries wearing a huge overcoat, into the lining of which he’d sewn oversized pockets that allowed him to hide and remove books with relative ease.

Another time at Harvard, Blumberg snuck in a pair of horseshoe-nail-pullers and used the tool to pluck out the lock cylinder of a library door and replace it with the blank he’d brought with him. He then went all the way to Montreal to get a locksmith to make him a master key for the Harvard lock (using the cover story that he needed a master made for the locks in an apartment building he owned). Blumberg then returned to Harvard and replaced the blank cylinder with the real one. He now had a master key that worked across campus.

Years later, while awaiting his trial, Blumberg told journalist Nicholas Basbanes:

“The chase really is something, isn’t it? It just gets worse, especially when you get so close to achieving the ultimate. It’s agonizing. Sometimes you wish you hadn’t started.”

Catching the Book Bandit

In 1988, Washington State University library staff discovered that highly valuable papers and books were missing from their collection, and campus police detective Sgt. J. Stephen Huntsberry was sent to investigate the case that would profoundly change his professional life.

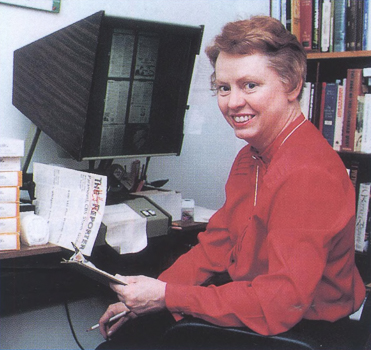

Huntsberry — a Navy veteran and former lounge singer — had no experience with rare books or libraries, but he took the case seriously and sought to learn as much as he could from the university’s librarians. One of those librarians was Eileen Brady, BA’65, a Creighton history alumna whose first library job was at Reinert. (She remembers a Creighton Jesuit teaching her how to read call numbers and shelve books, though she can’t remember his name.)

“I didn’t help Steve Huntsberry so much with his sleuthing, but I did help broaden his understanding of libraries and the weird people who sometimes worked there,” says Brady, now retired, from her home in Moscow, Idaho. Huntsberry noted Brady’s “extensive knowledge of the inner workings of library facilities, including a wealth of statistical knowledge about library theft.” The investigation and their ensuring friendship ended up setting Brady’s career down a slightly different path.

Brady had always had eclectic interests. Before becoming a librarian, she worked as a researcher assisting the artists, engineers and architects who made Disney World in Orlando. She also worked as a fact checker for golden-age TV series like Mission: Impossible, Star Trek and The Wild Wild West. (Read more about Brady and all the unexpected things a Creighton history degree can prepare you for.) But it wasn’t until Brady met Huntsberry that she really started digging into the field of library security, eventually becoming a nationally renowned expert on the subject.

Years after Blumberg’s trial, Brady, Huntsberry and a friend founded a quarterly publication called Focus on Security. In her research, Brady discovered that libraries had 3% to 15% of their materials stolen each year, very little of it ever recovered.

Huntsberry and Brady were later invited to speak at the Smithsonian’s National Conference on Cultural Property Protection. The same year, 1996, they testified as expert witnesses for the prosecution during Blumberg’s probation hearing. It was the only time Brady ever saw Blumberg in person.

“I remember the prosecution put me on the stand and said, ‘Why does what Blumberg did make any difference? They’re just books,’” Brady says. “I said, ‘Well, we get very upset when art objects are stolen because they’re representative of a particular time in history. We should be just as upset at the loss of these books. Because it’s the loss of human thought at a particular moment in time. It’s the theft of our shared cultural history.”

Back in 1988, with Brady and other librarians’ assistance, Sgt. Huntsberry determined that the items known to be missing from Washington State University’s libraries added up to almost 400 books and about 2,500 manuscripts, valued at roughly $500,000. Huntsberry, who died last year, left behind extensive documentation of the case, along with his personal account.

“There were no leads or evidence on which to begin the investigation,” he wrote in 1991. “All persons remotely associated with the library were instantly placed on the suspect list … but from the early stages of the investigation, I believed that outside players were responsible.”

His investigation led him down a few false trails, each one more sensational than the last. He looked into:

1. A team of book thieves whose methods resembled “something between the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers.”

2. The homicide of a rare books dealer in Texas.

3. A master forger and bomb-maker in Salt Lake City who murdered two people with explosives.

Huntsberry didn’t know it yet, but by the late ’80s, a few university libraries had begun to notice some very important rare books missing from their collections. He sent out warning flyers to other institutions he thought might be vulnerable to similar thefts — mostly colleges, universities and public libraries on the West Coast. He heard back from two: the University of Oregon and California’s Claremont College were missing similar materials. Huntsberry also heard from an LAPD detective, who said that libraries in the area had taken note of a suspicious character named Matthew McGue.

The big break in the case came a few minutes shy of midnight, April 18, 1988, when a custodian at a library at the University of California at Riverside found Blumberg sneaking around a restricted area that had closed several hours earlier. The library called campus police, who found in Blumberg’s possession a briefcase containing long, thin dental picks, clippings of a student newspaper article about the lack of campus police officers and another that listed library hours.

Blumberg was arrested for trespassing and possession of burglary tools and booked under his alias of Matthew McGue. A police officer who found a Washington State University library schedule card among Blumberg/McGue’s effects contacted Huntsberry.

“My elation was quickly subdued when I was informed that McGue had been released,” Huntsberry wrote. “I was convinced that McGue would go underground, assume a new identity and continue as before.”

Fortunately, Riverside police had photographed and fingerprinted McGue, and later sent the images and prints to Huntsberry. He teletyped every state in the U.S. asking for info about “McGue.”

(Huntsberry had already ruled out the real Matthew McGue, the University of Minnesota professor whose faculty ID Blumberg had stolen and who, incidentally, would end up testifying for the prosecution at Blumberg’s trial. McGue described his frustration and confusion at people repeatedly asking him about the research he was supposedly doing at libraries he’d never visited.)

A few weeks after he sent the McGue documents to “all 50 states,” Huntsberry got a hit on McGue’s print. The Minnesota State Criminal Investigation Department identified McGue as Stephen Carrie Blumberg, an individual with a long record of trespassing arrests. Huntsberry had his man.

“From that point on, it was just a matter of tracing Blumberg’s steps during his 20-year history of theft,” Huntsberry wrote. He compiled a comprehensive dossier on Blumberg and sent it to the FBI. And from there … the case went nowhere.

It’s unclear why it would take another two years for the authorities to roll up to Blumberg’s private library in Ottumwa, Iowa. An FBI agent who later arrested Blumberg admitted that they could have done more with Huntsberry’s tip, but they just didn’t think the pieces of his investigation fell into place.

For all Huntsberry’s meticulous detective work (and Creighton alumna Eileen Brady’s assistance), in the end, Stephen Blumberg was caught because a friend turned him in.

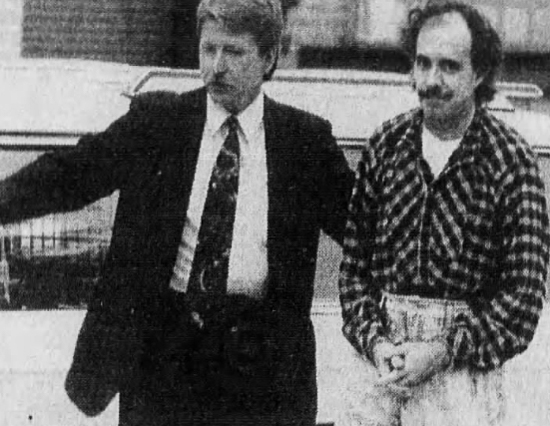

Kenneth J. Rhodes — Blumberg’s regular accomplice of 15 years — received a $56,000 reward for the tip. It was Rhodes, in fact, who led FBI agents to Blumberg’s door that night in 1990.

United States vs. Stephen Carrie Blumberg

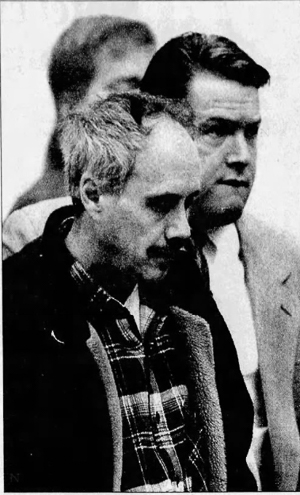

Blumberg had stolen millions of dollars worth of books and stashed them in his Iowa library. It was undeniable. So his defense lawyers had to try a wholly unique approach, a first in legal history. Blumberg’s 1991 federal trial (held in Des Moines) marked the only time a defense of not guilty by reason of insanity on the basis of bibliomania had ever been used in an American court of law.

A psychiatrist for the defense testified that Blumberg stole the books because he was suffering from delusional paranoia. The claim had plenty of evidence in its favor. Blumberg had been diagnosed with a schizophrenic personality disorder at the age of 15 and had been hospitalized multiple times for mental health issues since. Some members of his family had a history of mental illness, as well.

The defense’s psychiatrist said Blumberg was convinced that the government “was trying to prevent the ordinary man from having access to seeing these rare works of beauty. He would somehow liberate and preserve them and thwart this government plot.” Blumberg’s would only deepen his convictions in prison, falling in with a militant group called Posse Comitatus, who espoused an ideology denouncing all federal authority.

The prosecution’s own psychiatrist claimed there was no evidence that Blumberg was mentally ill. The case’s prosecutor, Assistant U.S. Attorney Linda Reade, put it bluntly: “Just because (Blumberg) wears his underwear a long time doesn’t mean he’s mentally disturbed.” She was referring to a detail that came out during the trial, that Blumberg liked to buy Victorian-era underwear and would, reportedly, wear some pairs for weeks at a time.

Blumberg himself never took the stand because his defense team thought he would seem too normal to the jury. Blumberg also didn’t talk to most of the reporters covering the story. Though two journalists would gain his trust later on — the aforementioned Nicholas Basbanes (who wrote about Blumberg in the book A Gentle Madness) and Philip Weiss (who wrote the story “The book thief: a true tale of bibliomania” for Harper’s Magazine in 1994).

When they asked him his motives and his methods, Blumberg gave a series of colorful (and sometimes contradictory) answers that underlined his mistrust of the government and contempt for librarians:

“I’m not bragging or anything, but I’m pretty ingenious with resources, if you know what I mean. If one way isn’t amenable, I can figure out three or four other ways to get inside (a library).”

“I figured a book was a silent source of wisdom, and if I illegitimately obtained it from neglect, of mainly the government, I was to use it. Guard it. Preserve it for others.”

"You know, I figured I was the mere custodian of those books. I would keep them, share them, pass them on to somebody else. Who really has the right to possess knowledge?"

“I’m in (prison) for having books that had been borrowed from the library, overdue library books.”

“Let’s put it this way: They were sort of an interlibrary loan to me. That’s what I figure. I don’t know if that’s how they would consider it, but that’s the way I look at it. Because I always intended to give everything back. I don’t regret putting the collection together, but I regret my inconsideration of others.”

Blumberg later told another journalist that he thought his life story would make an interesting book. He said he would title it “Book Collecting for Fun and Profit.”

After the trial’s closing arguments, the jury returned from its lunch break and rendered a guilty verdict. Blumberg was convicted on four federal counts of possession and interstate transport of stolen goods.

While he was out on bail and awaiting his sentencing, Blumberg repeatedly returned to the Omaha Project warehouse to help with book identification (in the hopes of gaining the judge’s leniency). Blumberg later recalled his annoyance at how the FBI and librarians had arranged “his” books. (“I had everything in perfect order. All my organization was gone. It was no longer a collection.”)

The judge sentenced Blumberg to 71 months in a minimum-security federal prison, plus a $200,000 fine. His fellow prisoners called him “The Book Man.” Blumberg later reported that he got a lot of reading done in prison. And writing, too, apparently.

In addition to writing a letter to Creighton about his intention to reclaim “his” books from the University, Blumberg sent taunting Christmas cards to the director of Ottumwa Public Library every holiday season. A few years later, after he was released from prison, Blumberg visited the Ottumwa library basically just to troll the library director. “As long as I’m here,” Blumberg told him, “I might as well get a library card.” His request was denied.

While he was in prison, Blumberg had also maintained correspondence with an 18-year-old man serving a sentence (at a different prison) for burglarizing several churches. The seasoned thief offered the younger man advice in his future pursuits: “Work the obits and death notices. Minneapolis is loaded with rich old ladies living in old mansions stuffed with antiques and rare coins and jewelry.”

Blumberg served about four and a half years before his release at the end of 1995. As a result of his 1996 probation hearing — thanks in large part to the expert testimony of alumna Eileen Brady — Blumberg received an unprecedented restriction. The court ruled that he must present a note whenever he entered a library or bookstore. The note read:

“My name is Stephen Carrie Blumberg … In 1991, I was found guilty by a jury of interstate transport of stolen property (rare books that I had stolen, mostly from libraries). I was sentenced to prison and served about five years. I have been released … and a condition of my supervised release is that whenever I enter a library or bookstore, I must, on entry, present this notification and that I consent to a search of my person and belongings upon arrival and departure.”

Another condition of Blumberg’s probation prohibited him from entering abandoned houses or buildings. He didn’t comply. In 1997, he was arrested for stealing fixtures and antique furnishings from a Des Moines home. The following year, he was tried for the second time, this trial held at the Drake University Legal Clinic, where 115 law students observed the proceedings.

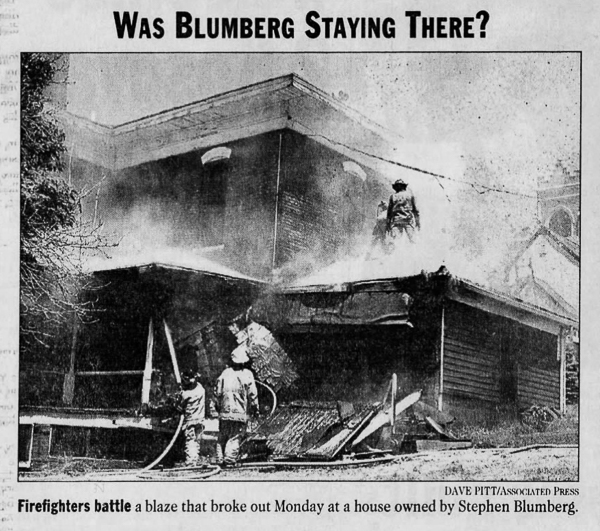

Blumberg was found guilty and sentenced to another five years in prison. Though he was apparently released on probation within a year or so. In 1999, a fire broke out at Blumberg’s old, abandoned Ottumwa home. Authorities found that someone had been sleeping there, on a pallet with relatively fresh bedding. They suspected it was Blumberg. The house was torn down later that year.

The last time Blumberg popped up in the news was in the early 2000s. On July 3, 2003, he was arrested again, this time mid-burglary. Police found glass cutters, hacksaws, pry bars and several antique doorknobs in his 1946 Chevrolet panel truck parked outside the unoccupied house he was in the process of looting.

He pleaded guilty, was sentenced to five years supervised probation, violated his parole and returned to prison for a stint. There are no records of him being arrested since then.

Blumberg has not, as far as anyone knows, delivered on his promise to reclaim his stolen books from Creighton’s Reinert library.

Back on the trail

This past spring, Creighton archivist Pete Brink was in the (heavily secured) Rare Books Room looking through an old box of files labeled “The Omaha Project.”

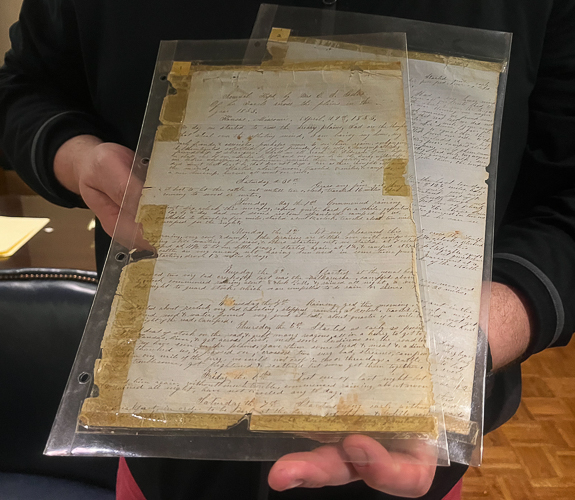

Brink was co-teaching an honors class on the subject, and he was hunting for any materials that might be useful to the class. All the books the FBI had given Creighton 30 years ago had been cataloged (or donated to other libraries), but some of the papers remained unlisted. Looking through this box of stray papers, Brink found the journal of Elizabeth Goltra, which chronicled her family’s 1853 journey on the Oregon Trail from Missouri to Oregon.

Brink’s first thought: Why does Creighton have this? His second: I bet we could find out who this belongs to.

“I did a quick search online and immediately found that the University of Oregon in Eugene had a collection for this woman,” Brink says. “That gave me goosebumps. It meant we might have the original that Blumberg had stolen.”

Blumberg’s theft of the University of Oregon collection had been particularly difficult for its librarians. In 1987, a researcher whose family had donated a trove of irreplaceable materials to the University of Oregon decades prior came to the school’s archives to examine a particular item. It was missing; as were, it was soon discovered, about 20 linear feet of papers — thousands of pioneer diaries, letters, railroad records and Indian treaties, all gone.

The donor was furious. Multiple university employees were questioned and even asked to take lie-detector tests. Over the next two years, the four librarians in the special collections that had been burglarized resigned from their positions. The university’s curator of manuscripts left the profession altogether, feeling that she could never again regain the administration’s trust.

(Cases like this, as much as anything, explain how Blumberg was able to get away with stealing tens of thousands of books. When the librarians discovered that the materials were missing, they knew they would become the primary suspects, which likely made them reluctant to report the theft.)

This spring, Brink called the University of Oregon’s director of special collections and university archives, David de Lorenzo, and learned that, yes, Elizabeth Goltra’s journal had been missing from their collection for more than 35 years. It was an especially notable absence, too, as Goltra’s is one of the oldest diary accounts of life on the Oregon Trail.

This May, the diary made its second journey to Oregon — 170 years later — when Brink, in town for an archivists’ conference, handed the long-lost item to de Lorenzo. Brink says it’s thrilling to see that Creighton students, faculty and staff are adding another chapter to the Blumberg story. (Listen to our podcast interview with Brink.)

“The students seemed to have a blast,” says Trish Ross, a historian and assistant professor in the Honors Program and Department of Modern Languages & Literatures who taught the Blumberg class with Brink. “The honors class was a humanities lab, so students were learning how to do research using different types of sources,” including first-person accounts. (Listen to our podcast interview with Ross.)

An FBI agent spoke with the class. As did Arnette Payne, BA’73. Shortly before she died this spring, the longtime Creighton librarian (who worked as a cataloger for the University bookstore in recent years) told the class about her work on the Omaha Project and the sense of mission she felt helping to restore so many plundered collections.

The class spent the second half of the semester building an online exhibit called The Book Bandit: Rare Books, Libraries and Theft. The exhibit used the Blumberg case as an entry point to explore the history of books and libraries, though its reach extended much further.

Students planning law careers explored the legal issues of insanity on the basis of bibliomania. Creighton psychology and neuroscience students created a page about hoarding and obsessive-compulsive disorders in the context of Blumberg’s crimes. (“I’d never heard about him before this class, and so much about this story blew my mind,” says Ava Szatmary, a class of 2024 psychology student.)

The eclectic nature of the course reflects Creighton’s commitment to placing the humanities at the heart of all disciplines, its belief that all areas of knowledge are “branches from the same tree.” And you never know where those branches might lead you.

Given everything that happened with the University of Oregon librarians, Brink says, the return of the Goltra journal and the collection’s restoration feels a bit like the healing of an old wound. There are, perhaps, more wounds to be healed.

“It feels great to return something to where it belongs. And now we have much more powerful tools to see if there are other materials still missing from collections across the country.”

All this exciting detective work, Brink says, has inspired them to ask what other items they can find. What other collections can they restore? What other treasures remain lost, awaiting their return, long overdue?

* * *

Listen to the podcast about the Blumberg case and the Omaha Project

* * *

Sources:

A Gentle Madness by Nicholas Basbanes

The Book Bandit: Rare Books, Libraries and Theft

“The Book Thief: a true tale of bibliomania” by Philip Weiss

“Biblioklepts,” Harvard Magazine

Various issues of the Creightonian newspaper and Window magazine, courtesy of the University Archives and Special Collections

“The Legacy Thief: The Hunt for Stephen Blumberg” by J. Steve Huntsberry, The University of Chicago Press Journals

Focus on Security issues from 1996, 1997 and 2003, including the articles “A Crazy Life: An Interview with Stephen Carrie Blumberg” by Tricia DeWall and “The Stephen Carrie Blumberg Probation Hearing: We Meet At Last!” by Eileen Brady and J. Stephen Huntsberry

“The most successful book thief in American History” by Kelly Jensen, Book Riot

“Man writes novel chapter in annals of library thefts” by Laurie Becklund, Los Angeles Times

“The Compleat Collector” by David Maraniss, The Washington Post

“Suspect in theft of rare books ‘loved old things’ by Rogers Worthington, Chicago Tribune

“Library receives rare books from the FBI,” The Creighton Cornerstone, Fall 1993

“Man is guilty of stealing thousands of books,” The New York Times