Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

I think (my Creighton education) was one of the keys to doing all these various things. Had I not had this broad base, I probably would not have been as, well, we’ll use the word 'successful.'

By Micah Mertes

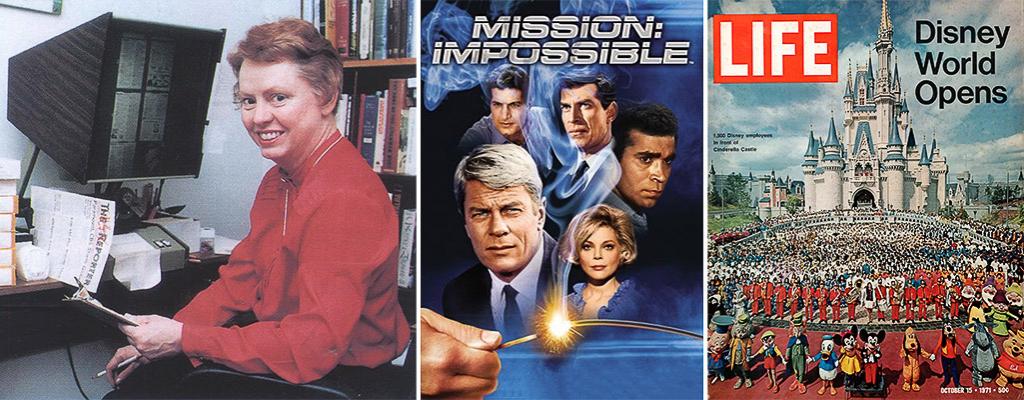

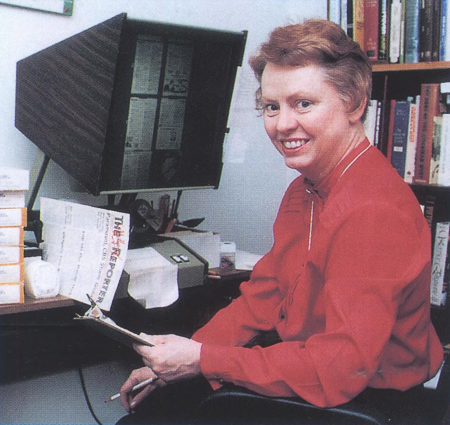

Few alumni illustrate the eclectic possibilities of a Creighton history degree quite like Eileen Brady, BA’65.

Brady, who also minored in biology and philosophy, worked for the bulk of her career as a librarian, starting with public libraries in Los Angeles and Spokane before beginning her 31-year career at Washington State University. But before that, Brady went to Hollywood.

When she arrived at Creighton, she wanted to become a physician. Though a few years of premed courses helped her realize the profession wasn’t for her. Instead, she was able to finish with a history degree by cramming four years’ worth of upper-level credits into her senior year.

But where to go from there? Brady had read a book by a Hollywood producer about TV and movie studio research, and she found it a fascinating career prospect. Appropriately enough, the first place she went next was the Omaha Public Library. She asked a librarian for telephone directories for Los Angeles, got addresses for a long list of studios and sent letters to their research departments.

She ended up landing a gig for de Forest Research Inc., a company that checked the accuracy of the scripts for such classic TV shows as Star Trek, I Spy, The Wild Wild West and Mission: Impossible. (The latest installment of Tom Cruise’s wildly successful Mission: Impossible movie series hits theaters this month. Brady, while forever a fan of the original TV series, has no interest in the movies.)

In the pre-Internet days, Brady and her colleagues would comb through the scripts checking dates, locations, names (fictional characters couldn’t hew too closely to a real person). Proper pronunciation was also a factor. For a series of 22 scripts with Native American characters, for instance, Brady studied the Lakota and Dakota Sioux languages and rewrote their dialogue to be phonetically correct.

After her time as a script reader, she got an arguably even more interesting job, a researcher for WED (Walter Elias Disney) Enterprises, now known as Walt Disney Imagineering, the company responsible for designing and building Disney World in Orlando.

As a Disney researcher, Brady assisted the artists, engineers and architects who developed the park. From rides to safety regulations to fire codes to park plastics, when it came to Disney World, Brady did a little bit of everything. She researched pirate costumes and coves for the Pirates of the Caribbean exhibit; she helped engineers find designs and specifications for the hologram used in The Haunted Mansion; she studied the monorail systems of Japan to help engineers create Space Mountain.

Years later, after she became a librarian, Brady played a small part in a real-life adventure of sorts — the investigation and pursuit of the most successful book thief in American history. (Read all about it here.) It was a fitting role for Brady, once described by a colleague as a “Renaissance librarian who can ferret out answers to the most difficult questions.”

I actually wrote an in-depth article about the book bandit case that we’ll publish later this month. In the meantime, here’s our interview with the Creighton alumna and her mission, which she chose to accept, to bring a little accuracy to some of the 20th century’s most iconic amusements.

What were some of the daily tasks of 1960s TV researcher?

I’ll give you an example. In the original Star Trek TV show, Gene Roddenberry had made a pilot that didn’t get picked up and then had the chance to make a second pilot. Among the first things I did while reviewing the new script was checking that the name “James Kirk” didn’t conflict with a real person.

We didn’t have computers yet, so I went through military records to see that no officers went by that name or other character names on the show. Of course, Trekkies know that the character’s full name is “Captain James Tiberius Kirk.” I couldn’t find a Tiberius anywhere, so we were safe.

This was to avoid lawsuits, right?

It was. Before I started at de Forest Research, there was a very popular TV show about a neurosurgeon called Ben Casey. They had an episode with a bad guy in it, who was a physician living in a particular town. It turned out there was a physician with the same name and working in the same medical specialty who lived in that same town. He sued the production company for millions of dollars. So you looked for problems like that, for the instances when a character might conflict with a real person. It was the same for products. If there was a perfume name in the script, we had to make sure there wasn’t such a perfume.

What other things did you check for?

After the names, you got down into the nitty gritty of what was in the script itself. Dialogue, descriptions. You looked for accuracy, even in a somewhat sci-fi show like The Wild Wild West. You go through the scripts checking terminology and looking for contradictions that might confuse viewers.

Outside of checking for any real Captain Kirks, what was it like “fact”-checking a futuristic sci-fi show like Star Trek?

That show might have been assigned to me because neither of my colleagues had any science background whatsoever. But I, at one time, thought I had wanted to be a physician, so I was, in essence, a premed undergraduate. I’m afraid Creighton’s organic chemistry class wiped that notion out of my head. But I had learned enough that I could at least pronounce the words.

You worked on a wide range of shows: sci-fi, Westerns, action, modern, period pieces.

I got to sign off on anything that was a Western because neither of my colleagues had the foggiest idea about that kind of thing. My dad was raised on a cattle ranch in South Dakota, so I knew a number of things. Such as … you can’t run your stagecoach for 30 miles without a change of horses; you would have killed them in a couple of miles. Another thing that always puzzled me on action shows was when a good guy took refuge in a gunfight behind a couch. That’s not stopping the bullets, dummies.

How did the screenwriters and showrunners respond to your comments?

(Laughs) The one response I really remember was when an irate producer called me saying, “What do you mean we can’t put a silencer on a revolver!? We do it all the time!” And I said, “Well, anybody who has any knowledge of guns whatsoever is laughing at you when you do. All the gases come out of the cylinder, and that’s what makes the noise. Putting something on the end of the barrel isn’t going to do any good.” He says, “Oh, nobody knows that!” And here's what I told him. I said, “I’m a 21-year-old girl from Omaha, Nebraska, and I know that!” (Laughs)

Did they end up taking the note?

Yeah, in that particular case, they did.

The 21-year-old girl from Omaha won that round.

Of course, they didn’t always take the notes. There was this attitude that anyone who didn’t live on the East or West Coasts was pretty dumb so why worry about what “flyover country” thought about anything.

So, in a way, you were representing the Midwestern voice for all these TV shows.

Sometimes literally. One of the scripts I checked mentioned a character who had a “Nebraska twang.” I told them, “Do I have a twang?” They said I didn’t. “Well, I’m a Nebraskan, born and raised.”

You not only checked the accuracy of scripts for the Mission: Impossible TV series. You also got to know Peter Graves (who portrayed team leader Jim Phelps).

At the time, I was working for the Los Angeles Public Library and completing my master’s degree in library science at the University of Southern California. On the days I didn’t have class or a shift at the library, I would go to the studio lot. I knew a lot of people there, and I could get into the sound stages because I didn’t bother anybody. I stood in the back by the sound console on the set of Mission: Impossible a number of times. One day, Peter Graves walked up to me and introduced himself. That’s just who he was, a very kind Midwesterner. From then on, he would always ask me about my classes and the library branch where I worked. He would always invite me to the Mission: Impossible episode wrap parties on Friday evenings, and I really got to know the crew.

One of the reasons I wanted to talk to you now is that there’s a new Tom Cruise Mission: Impossible movie coming out in July. I believe it’s the seventh one. Have you seen any of them? That first 1996 one?

No, I haven’t.

Well, in that first movie, they made Peter Graves’ character, Phelps, the villain. Fans were pretty upset about it at the time.

Oh. (Laughs) Maybe that’s the reason I didn’t see it.

Do you watch any modern TV shows now?

I’ve watched the remake of Hawaii Five-0, things like that. It just doesn’t have the same edge. And I’m afraid I have a very strong Catholic morality streak, so that may not help me with my enjoyment of modern television.

Let’s talk about another really interesting job you had, with Walter Elias Disney Enterprises around the time they were creating Disney World. What does a Disney World researcher do?

Well, at first, I was hired to catalog their collection. Then other stuff came up, and they asked for help. Engineers, construction managers, electricians. Again, I had that weird mixture of skills and interests, and I wasn’t intimidated to dive into the technical stuff. So I worked on that, too.

Once they figure out you’ve got the skills to do something, then you’re on the hook for it.

Right. Yeah.

You’ve done quite a few very different things in your life.

I think the term is “eclectic.”

Did Creighton help prepare you for that?

I think it was one of the keys to doing all these various things. Had I not had this broad base, I probably would not have been as, well, we’ll use the word “successful.” (Laughs.) I might not have become a physician, but I knew how to pronounce the words others didn’t. And if I didn’t know the answer to a question, I knew how to find it.