Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

These students' grit, perseverance and enthusiasm reassure me that there will be many talented scientists who can carry this torch.

By Micah Mertes

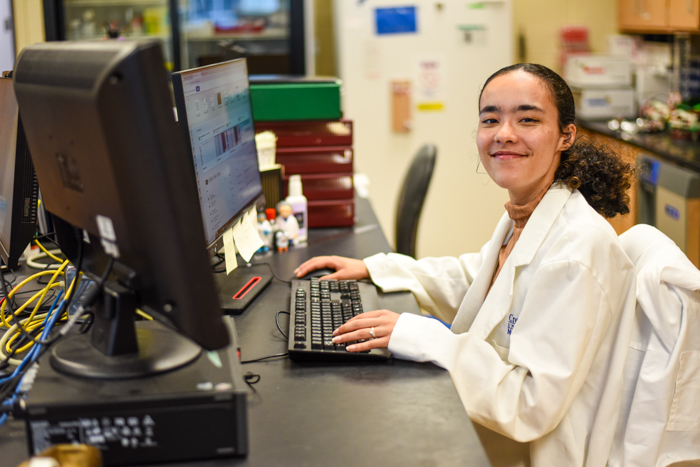

Being deaf or hard of hearing, especially as a child, can come with a profound sense of loneliness, says Kalia Douglas-Micallef. A total disconnect from the rest of the world.

Kalia, a rising college sophomore who grew up in Toronto, has managed the isolating effects of her hearing loss all her life. In elementary and high school, she struggled socially and (because she wasn’t accommodated) academically. She grew self-conscious of the ways her condition made her stand out — her hearing aids and the microphones her teachers wore to amplify their voices for her benefit. By the end of every school day, Kalia’s effort to follow lessons and conversations left her exhausted.

“When I was a kid, I would always get so excited whenever I saw someone else with hearing aids, which was rare,” says Kalia, a U.S. citizen and student at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada. “I’ve always longed for that connection, to meet people like me. I’ve always wanted to be in a place that gives me that sense of unity and support and understanding.”

For the first time in her life, a thousand miles from home, she believes she’s found it.

* * *

This summer, Kalia is working as a research intern at Creighton University’s Dr. Richard J. Bellucci Translational Hearing Center, joining a group of professors and students (undergraduate, graduate, doctoral and post-doctoral) developing solutions to preserve or restore hearing or inner ear function. The hearing center took the namesake of the pioneering alumnus last year.

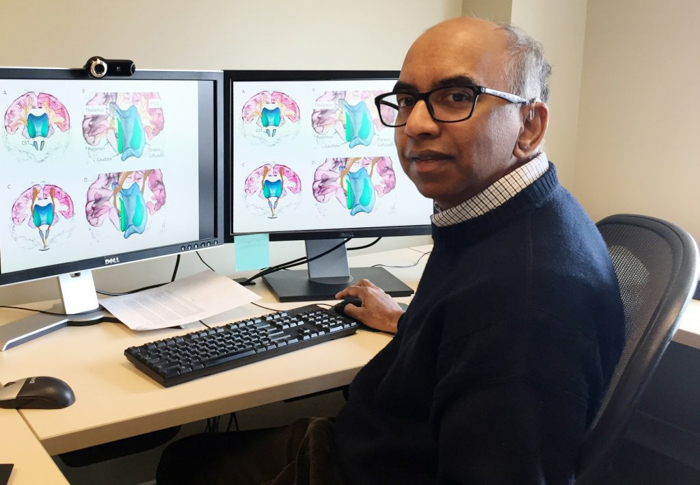

Kalia and her fellow intern Trinity Goodloe, a senior at Case Western Reserve University, came to Creighton through a National Institutes of Health grant awarded to Tilak Ratnanather, DPhil, at Johns Hopkins University to increase diversity in the biomedical sciences. Every summer for 34 years, Ratnanather has invited undergraduate students with hearing loss to work in his research lab. The NIH grant allows him to take his program nationwide, creating the STEMM Opportunities for College Students with Hearing Loss to Engage in Auditory Research (STEMM-HEAR) program.

For the next five years, STEMM-HEAR will bring eight undergraduate students to conduct summer research programs in one of four labs at four universities: Oregon Health & Science University, University of Southern California, Rice University and Creighton University. All participating faculty mentors, as well as Ratnanather, have some degree of hearing loss or dysfunction, including Creighton’s Peter Steyger, PhD, professor of Biomedical Sciences and director of the Dr. Richard J. Bellucci Translational Hearing Center.

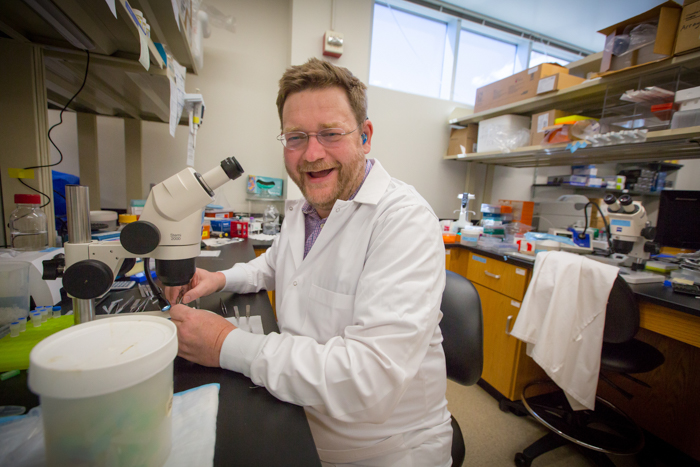

Steyger says the program aims to recruit more students with hearing loss into auditory or vestibular neurosciences.

“The program has the potential to create a community that brings additional lived experience to the Bellucci Center: hearing loss researchers who know what it’s like to live with hearing loss,” Steyger says. “This kind of real-life experience helps focus the research into real-world problems and real-world solutions.”

That’s where the translational aspect of the center comes in. Translational research translates discoveries made in the lab into practical treatments and therapies for patients. It’s the bridge connecting scientific research to the realities of the clinic. Plainly put, translational research is research that seeks to start helping people as soon as possible.

When we think about empathy in healthcare, the first pictures that likely come to mind are by the bedside: the comforting words and kind faces of nurses, physicians and other caregivers who not only treat their patients’ illnesses but connect with the human beings before them. In Creighton’s Jesuit tradition, they care for the whole person.

But empathy and humanity can be just as essential to making breakthroughs on the research side of the health sciences.

In the case of the Bellucci Center, Steyger says, that doesn’t mean that hearing loss research should only (or even mostly) be conducted by those with hearing loss; just that bringing more such researchers to labs across the country will yield richer results and, ultimately, greater benefits to patients. Students like Kalia and Trinity offer an essential perspective to the work.

“I want to bring my empathy and my experience into my research,” says Trinity, who’s majoring in psychology and communication sciences and disorders at Case Western. “Because I know this world, and I’m passionate about helping people who are dealing with some of the same challenges I have. So this has been the perfect place for me to be.”

Housed in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, the Bellucci Center’s research includes dozens of studies across the University. Faculty scientists work alongside undergrads and professional students training to become the next generation of hearing researchers. Projects range widely from lab to lab. For instance, this summer in Steyger’s lab, Kalia and Trinity studied hearing loss due to inner ear anomalies in individuals with Down syndrome. (Steyger was recently interviewed in Science magazine about the discovery of a Neanderthal skeleton with an ear malformity characteristic of Down syndrome.)

The number of students in the Bellucci Center will soon expand, thanks to a new R25 grant from the National Institutes of Health, which Steyger received to support graduate students from diverse backgrounds.

For Trinity, Kalia and Dr. Steyger, the research is deeply personal, not only due to their hearing loss but also how they lost their hearing — as a side effect of the emergency medications that saved their lives as young children.

Kalia was born three and a half months premature, weighing only one pound, 11 ounces. She was given an antibiotic that carried the known side effect of hearing loss. By her first birthday, she was wearing hearing aids.

Trinity contracted an illness as a newborn and was also given an antibiotic that saved her life. Over the years, her hearing loss progressed from mild to severe. She and her parents didn’t realize she was losing her hearing until Trinity’s second-grade teacher expressed concern.

And Dr. Steyger, when he was 14 months old, contracted bacterial meningitis. He was given a course of aminoglycoside antibiotics that saved his life but took his hearing.

In his research today, Steyger works to identify interventions that will ultimately allow clinicians to treat patients with this same kind of antibiotic (which 100,000 people are still prescribed each year) without the potential side effects of hearing loss, deafness or inner ear dysfunction.

Working in Steyger’s lab has “shown us things — about our disabilities, about our lives — that we didn’t know were possible,” says Trinity.

Kalia says she never could have anticipated how beneficial the experience would be, “not only in my career but in my personal life. I’ve come across things in the Bellucci Center that I never knew about. Technological advancement in hearing aids and other ways I can better accommodate myself. This has been transformative in so many ways.”

* * *

Simultaneously researching and experiencing hearing loss has been a continual process of self-discovery throughout Dr. Steyger’s career. The same has held true for many of his colleagues.

“In learning more about our condition, we find something fundamental about ourselves and why we are the way we are,” Steyger says.

“For me, it forced me to come to terms with the things that make me different from everyone else. It’s happened to me several times in my career, and it’s been emotionally difficult to deal with every time. But once you get past it, you feel free to ask the right questions and answer them. Then you can start working to improve others’ lives.”

Steyger mentioned one moment when advancements in research improved his own life dramatically.

Steyger used to speak very loudly. It was the only way he could hear his own voice (with the aid of his cochlear implant). About 14 years ago, after the tireless work of other researchers, Steyger received an upgrade to his implant, an algorithm tweak that changed everything. He could now hear his voice without having to shout.

He arrived home a short while later. He didn’t tell his family about the implant upgrade, but within minutes, they noticed the lowered volume of his speech. As did his friends and colleagues the next time they saw him.

“I hadn’t even realized the effect my loud talking was having on my relationships,” Steyger says (in his now soft-spoken voice). “I hadn’t realized that my volume was making others tense or think that I was upset. But I was really just trying to hear my voice.”

Now that he can hear himself better, he’s softer with others, which has greatly improved his interactions and relationships. It still amazes him that a seemingly incremental tweak could lead to such a profound impact on how he experiences the world.

Moments like this are what drive Steyger: the possibility of changing a person’s life, the opportunity to make someone feel less alone.

Steyger says he’s closer to the end of his career than the beginning, but working with students like Kalia and Trinity re-energizes him. “Their grit, perseverance and enthusiasm reassure me that there will be many talented scientists who can carry this torch.”

* * *

The STEMM-HEAR summer research program has helped Kalia hear (figuratively) her own voice more clearly.

“For the first time in my life, really, I feel empowered to speak,” she says. “I feel like I get to have a say and help find solutions for people like me.”

Kalia loved the summer research experience so much that she's decided to move to Omaha and transfer to Creighton for her sophomore year. She will always have a place in Steyger’s lab, he says.

Beyond the Bellucci Center, Kalia feels connected to Creighton in general. She and Trinity lived together over the summer in Davis Square. Wherever they looked — walking along the Mall, to Brandeis Dining Hall or through the halls of the Criss Complex — they saw friendly faces. Everyone said hello.

It’s hard to feel alone here.

* * *

About the Bellucci Translational Hearing Center

In the Dr. Richard J. Bellucci Translational Hearing Center, faculty scientists across multiple disciplines train the next generation of hearing researchers. Together, they seek solutions to preserve and restore hearing through the study of sensory cell regeneration, gene therapy and drug intervention.

The support of the Bellucci DePaoli Family Foundation has been vital to the center's success. Since an initial investment from the foundation launched the center in 2019, researchers have earned more than $8.5 million in research awards from federal and national funding bodies. The foundation’s support was also essential to securing a $10.8 million award from the National Institutes of Health-affiliated Centers for Biomedical Research Excellence funding mechanism — the largest federal grant in the history of Creighton University.

In 2023, the Bellucci DePaoli Family Foundation made a multi-year grant to the hearing center, which Creighton renamed to honor Dr. Bellucci’s legacy.

To date, the Bellucci Translational Hearing Center has received $1.4 million from the Bellucci DePaoli Family Foundation to fund seed projects, postdoctoral and predoctoral scholars and equipment needed by the center. The researchers’ work has resulted in dozens of papers and posters that have advanced the field, broadened the center's exposure and propelled the career trajectories of research scientists and trainees alike.

Since 2019, the hearing center and Creighton’s Department of Biomedical Sciences have hosted the annual Bellucci Symposium on Hearing Research, sponsored by the Bellucci DePaoli Family Foundation. At the symposium, researchers and clinicians from across the country come together to share and discuss the latest findings in their field.