Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

I’m grateful that my life has turned out the way it has. But I’m also grateful to the Jesuits for the education they gave me and for my year at Creighton.

By Micah Mertes

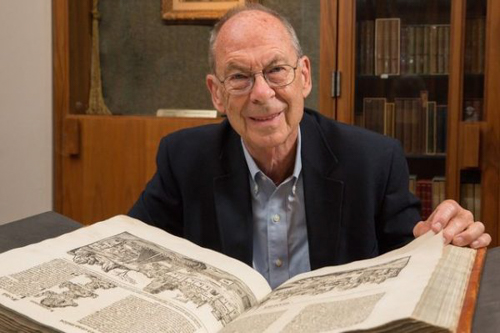

Writing a feature about a Creighton alumnus as interesting as Henry Ansgar Kelly, PhD, poses a unique challenge: Namely … where to begin? What do you focus on first?

We’ve decided to solve this problem by not making a decision. Instead, here’s a list of many reasons Kelly makes for such a compelling feature:

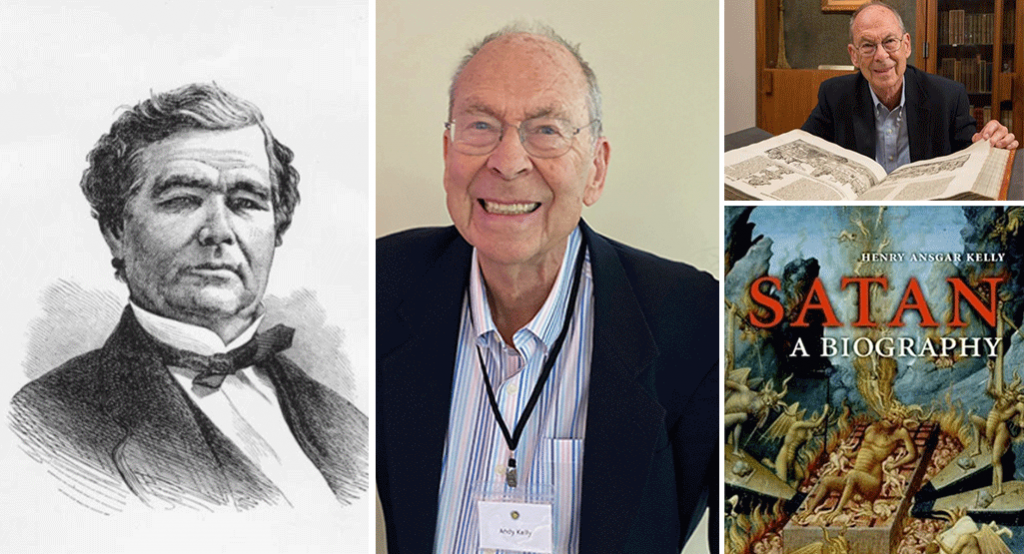

1. He’s one of America’s preeminent scholars on Satan. In fact, Kelly wrote THE book on the devil. His academic bestseller Satan: A Biography has been translated into six other languages.

2. Kelly met the real-life exorcist who inspired the bestselling novel and hit movie.

3. Kelly is an ordained exorcist himself.

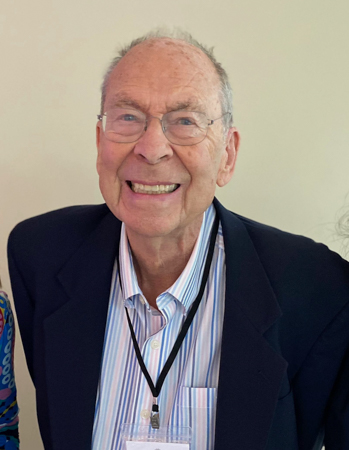

4. He was almost a Jesuit priest, just one year shy of completing the 14-year seminary curriculum for Jesuit scholastics.

5. He wrote a screenplay about Edward Creighton and the transcontinental telegraph.

6. Kelly’s daughter is a protégé of filmmaker Quentin Tarantino.

7. Kelly’s son has composed music for the TV series NCIS.

8. At 90, Kelly continues to be highly prolific. Technically retired since 2004, he’s a distinguished research professor emeritus at the University of California – Los Angeles, and in the past 20 years alone, he’s published more than half a dozen books and more than 40 articles.

9. Henry Kelly’s name isn’t really Henry. It’s Andy.

10. Henry/Andy Kelly has pre-written his own obituary, which notes the day he will die.

Creighton and the Jesuits

First, the name.

Kelly was born in the small farm town of Fonda, Iowa, in 1934, with the intended name of Harry Francis Kelly, Jr. But the town’s parish priest said that nicknames couldn’t be used in the baptismal ceremony and register. Instead, the priest put down “Henry” and also mistakenly gave Harry/Henry the middle name of “Ansgar” instead of “Francis.”

Kelly’s mother, Inez, was known as “Andy,” short for her maiden name, "Anderson,” and Kelly’s parents chose to name him “Andy Jr.” after his mother instead of his father.

Nine decades later, the man originally named Harry now goes by Andy or Henry, depending on the context. He’s lived a life befitting a man with three different first names.

Growing up in Fonda, Kelly became intrigued by the Society of Jesus. “I had read a lot about the Jesuits, and I could see they were the most intellectual of the orders,” Kelly says. “That’s what drew me to them.”

Kelly was advised to first go to nearby Creighton University to strengthen his handle on Latin before joining the seminary. He attended from 1952 to 1953 (but, he says, has remained a Bluejay ever since).

The same year Kelly left Creighton, his older brother, John Patrick (“Pat”) Kelly, BS'57, JD'60 — future Sarpy County attorney — finished his sophomore year there. Pat was the only member of the family to graduate from the University, which he did twice. (After his junior year, Pat was drafted and spent two years in the Signal Corps, later returning to Creighton to finish his bachelor’s degree on the GI Bill, then completing his law degree.)

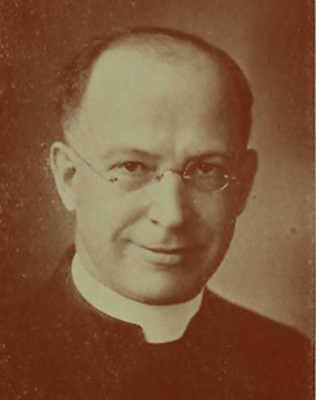

Andy Kelly’s sole year at Creighton was, in many ways, foundational. It’s where he discovered his love of scholarship. It’s where he met the two Jesuits who inspired him to stay on his path to the priesthood (residence hall namesake Rev. Francis Deglman, SJ, and Rev. Norbert Lemke, SJ). It’s where his resolve as a future seminarian was almost immediately put to the test.

“There was a complication during my Creighton year,” Kelly says now. “I fell in love with a girl who worked at the library. There was nothing practical about it. She was a senior, and I was a freshman. It couldn’t have worked.”

In 1953, with a newfound Creighton education in Latin, Kelly began his work in the seminary, joining the newly founded Wisconsin Province of Jesuits. Over the next 13 years, he spent time in the Missouri Province, earned degrees in the classics, English and philosophy at St. Louis University, earned his PhD at Harvard University and studied at the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry as a Jesuit scholastic, where he spent much of his time on demonological research, in addition to theology, scripture and canon law.

In 1966, Kelly realized that the life of a Jesuit wasn’t for him and formally requested a dispensation from the Pope to release him from his perpetual vows of poverty, celibacy and obedience.

No longer an aspiring priest, he spent much of the next year abroad, renting a room at the American Academy in Rome, which, he says, served as “a suitable halfway house between the religious and secular life.”

In Rome, Kelly met his future wife, Marea Tancred. She had moved to Italy from Australia a few years earlier, taking a job as a switchboard operator for American bishops during the last year of the Second Vatican Council. The following year, Kelly joined UCLA as an English professor. He’s remained there, except for sabbaticals, ever since.

“I’m grateful that my life has turned out the way it has,” Kelly says. “But I’m also grateful to the Jesuits for the education they gave me and for my year at Creighton. Everything I’ve learned has been so valuable and gratifying in my life.”

Kelly says he “never made it out of the minor leagues” as a Jesuit. But before he left the seminary life, he was ordained to four minor clerical orders: usher, lector, acolyte and exorcist.

Giving the devil his due

In 1960, the same year he was ordained as an exorcist, Kelly met the exorcist: Rev. William Bowdern, SJ, whose reported 1949 exorcism of a 14-year-old boy in St. Louis inspired William Peter Blatty’s novel The Exorcist and the subsequent 1973 hit film of the same name. (Learn about Creighton’s connections to that real-life case here.)

At the time, Kelly was studying scholastic philosophy and American literature at St. Louis University. While exploring the history of the Salem witch trials, Kelly became fascinated with the devil (in a purely academic sense).

Bowdern — incidentally, the brother of Rev. Thomas S. Bowdern, SJ, Creighton’s 17th president — happened to be living in the same campus building as Kelly, who asked the elder Jesuit if he could interview him. (Kelly says now that he was the only person ever to interview Bowdern.)

“It was a great opportunity because he was willing to tell me everything,” Kelly says.

Kelly recounted to Bowdern the most colorful details he’d heard about the real-life incident. Bowdern quickly shot most of the stories down as sensationalized, if not fantastical. (Kelly later included details of the interview in the second edition of his book, The Devil, Demonology, and Witchcraft, 1974.)

After that experience, Satan and demonology became some of Kelly’s primary areas of scholarship. He’s since written over 20 books or publications tracking the evolution of Christian beliefs surrounding the devil and his minions. Titles range from the scholarly (“The Metamorphoses of the Eden Serpent During the Middle Ages and Renaissance,” The Devil at Baptism: Ritual, Theology and Drama) to the slyly humorous (“Satan the Old Enemy: A Cosmic J. Edgar Hoover,” Satan: A Biography).

In his 2017 book, Satan in the Bible, God’s Minister of Justice, Kelly lays out his thesis:

Satan has long been seen as God’s eternally evil enemy, determined to keep as many beings as he can from entering the heavenly kingdom. But this understanding dates only from the distortions of post-Biblical times, when Satan was reconceived as Lucifer, a rebel angel, and as the serpent in the garden of Eden.

Kelly says that a later misreading of Satan as radically depraved transformed Christianity into a highly dualistic religion, with an ongoing contest between good and evil.

“But Satan wasn’t originally God’s enemy,” Kelly says. “He was His henchman. Seeing Satan in his true nature, as a cynical and sinister celestial bureaucrat, will help to remedy this distorted view.”

From the start of his career at St. Louis University through his time at Harvard and UCLA, Kelly has found the devil to be an endlessly fruitful research track.

“As researchers,” he says, “we always have our eyes on the main prize of doing something original and fascinating. That’s what we scholars are on the lookout for.”

As far as scholarly research goes, penning the devil’s biography is pretty darn original and fascinating. Examining the origins of the Bible has likewise allowed Kelly to continually challenge our modern conceptions of good and evil.

It’s important to note that Kelly’s Satan studies make up just a fraction of his bibliography. He’s also written four books on Chaucer, three on the genre of tragedy and one on Shakespeare. He’s likewise published works on Biblical studies, Church history, canon law, theology, the Inquisition, the heresy trials of Sir Thomas More, and medieval and Renaissance literature and history. (Kelly believes himself to be one of the most published authors ever to attend Creighton.)

And yet, however eclectic Kelly’s interests, he keeps circling back to his career-long campaign: to write the definitive revisionist history of the devil himself.

Creighton: The Movie

Kelly has also long been interested in another individual, this one much kinder and less prone to controversy: Edward Creighton.

During his time at Creighton, Kelly not only became imbued with the spirit of the place but its history. He read up on the University’s origins and founding family.

Years later, in 1960, when Kelly was a Jesuit scholastic at St. Louis University, he realized the 100th anniversary of the construction of the transcontinental telegraph system was coming up the following year. University founder Edward Creighton had led the telegraph’s construction in the 1860s, connecting the eastern network in California via his home of Omaha. (Read more about how Creighton united a nation here.)

Kelly thought Creighton’s story was so compelling it deserved its own movie, ideally in time for the telegraph’s centennial. One of his fellow scholastics, Joe O’Shea, SJ, was a bit older than Kelly and had some experience in filmmaking. Together, they came up with an idea for a movie scenario chronicling Edward Creighton’s adventure of constructing the telegraph.

They called it The Admirable Creighton and the Transcontinental Telegraph.

What they wrote wasn’t a full script with dialogue but a scenario that outlined the “cinematic incidents” that would fill out the movie.

Here’s an excerpt from the scenario — its conclusion, in fact — that illustrates Andy Kelly’s affinity for Ed Creighton, the University he founded and the city where they made their home:

“(Edward Creighton), alone, had the foresight to found a great University of the West — to assure for this country a steady supply of teachers (shots of modern schoolroom) and of professionals (shots of doctors, dentists, lawyers) … Creighton’s was not an idle dream but one which has come true. It is fitting that the center of the Free World’s greatest communication network should be located at Omaha — a network ever on the alert to defend the blessings of freedom to all men, everywhere! (Shots of the Strategic Air Command Communications Center). Cut to the martial music of the air corps. B-52s in the air over Creighton University. And on and up into the very sun itself.”

Kelly and O’Shea sneaked into the SLU president’s office to make copies of the script using his Xerox machine. They were eventually caught and chastised.

But it was worth it, Kelly says. They now had four copies of the final product. And, more importantly, they had a connection to Hollywood.

Linda Hope, the daughter of comedian Bob Hope, was attending SLU at the same time as Kelly and O’Shea, and she agreed to recommend their script to her father.

A few weeks later, Rev. Carl Reinert, SJ, president of Creighton University, was in St. Louis visiting his brother, SLU president Rev. Paul Reinert, SJ (whose copy machine Kelly and O’Shea got in trouble for using). “We managed to see Fr. Carl Reinert and make our pitch to him,” Kelly says. “He seemed interested, so we gave him the final copy of our opus. We later learned that he, too, sent the script to Bob Hope.”

Bob Hope never got back to them. Kelly was disappointed that he wouldn’t get his movie made in time for the telegraph’s 1961 centennial. (There was, to be sure, already a 1941 movie about the telegraph line’s construction called Western Union, but Kelly and O’Shea’s film would have focused much more on Edward Creighton himself.)

Though Kelly never broke into Hollywood, his children did. His daughter, Sarah Kelly, is a protégé of filmmaker Quentin Tarantino. She worked as a set production assistant on Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction and directed Full Tilt Boogie, a documentary about the making of From Dusk Till Dawn, which Tarantino co-wrote and stars in alongside George Clooney and Salma Hayek.

Andy Kelly’s son, musician Dominic Kelly, has also worked in the industry. Dominic has licensed hundreds of his tracks to CBS for the shows NCIS, NCIS New Orleans and NCIS Hawai’i. For fans of the show, any time a scene takes place in Abby’s forensics lab, the music you’re hearing has likely been composed by the son of a one-time Creighton student who was almost a Jesuit but decided instead to become Satan’s biographer and Ed Creighton’s Hollywood agent.

More than 60 years since he wrote the Creighton script, Kelly hasn’t given up hope on it getting made. (Though he has, of course, given up on Bob Hope making it.) There’s still time, Kelly says, for the story to be adapted by Creighton University’s 150th anniversary in 2028.

Kelly anticipates the project’s eventual success in his own obituary. Here’s what will soon happen, he writes:

“(The Admirable Creighton) was revived in 2024, when the scenario was exhumed and seen as deserving of Creighton University’s support as part of celebrating its 150th anniversary. The result was not a feature film but a six-part limited series called Ed Creighton of Western Union, starring Russell Crowe as Edward Creighton and produced by David E. Kelley. The series screened on Netflix in 2027 to great acclaim.

“It was nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Writing for a Drama Series, acknowledged as ‘based on The Admirable Creighton and the Transcontinental Telegraph by Joseph O’Shea, SJ, and Henry Ansgar Kelly.’”

The last day of Andy Kelly’s life

The Russell Crowe Netflix series about Ed Creighton isn’t the only future development Andy Kelly claims to foresee. His obituary also notes the date of his death.

Kelly will, he writes, pass away on June 6, 2035, his 101st birthday. His obituary reads:

“During the last decade of Andy’s life, he was still hard at work on various projects, and a good number of posthumous works are forthcoming. During his waning years, he was lovingly tended to by Marea, in spite of her own waning, and their children.

“His funeral will be celebrated at Corpus Christi Church on June 18, 2035 (his and Marea’s 67th wedding anniversary), with a Requiem Mass, complete with black vestments, at his request, rather than the now usual Mass of the Resurrection with white vestments. The Los Angeles Chamber Group will play Fauré’s ‘Requiem’ as part of the service. Interment will be at Holy Cross, in a plot he and Marea long ago selected for its expansive view.”

(The obituary’s text, Kelly says with a laugh, is “subject to revision, of course.”)

Kelly — a man clearly fascinated by death — has always liked to quote Hamlet’s graveyard musings.

In particular, he’s fond of the first scene of Act 5 in Shakespeare's play, the “gravedigger scene,” when Hamlet ponders over the skull of a man who might have been a lawyer.

What remains of this man now, this skull? Where can his essence be found? “Where,” Hamlet asks, “be his quiddities, his quillets, his cases, his tenures and his tricks?”

Andy has the answer, at least for himself: “They be in his writings.”