Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

What I cherish most about Creighton is this: The University took the time and care to make me feel important. To make me know that I matter. In my career, I’ve tried to do the same for every patient, every student, every person I meet.

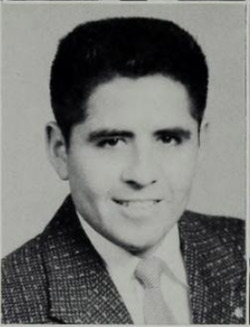

George Blue Spruce Jr., DDS’56 — assistant dean of American Indian affairs at A.T. Still University-Arizona School of Dentistry & Oral Health — recently received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation Awards for Excellence in Social Mission in Health Professions Education.

A member of the Laguna/Ohkay-Owingeh Pueblo tribes of New Mexico, Blue Spruce was also the recipient of the 1984 Alumni Achievement Citation, Creighton’s highest alumni award.

* * *

By Micah Mertes

Sixty-five years ago, George Blue Spruce Jr. took the stage at Creighton commencement to become the first American Indian dentist in the nation.

As Blue Spruce stepped before Carl M. Reinert, SJ, to receive his diploma, the then-Creighton president paused the ceremony and asked for Blue Spruce’s parents to please stand. They were met with a long round of applause for their steadfast support of their son, for their family’s achievement.

“I can’t describe the joy I felt at that moment,” Blue Spruce says now. “The joy I still feel.”

His parents’ dream — long before he and his siblings were born — had been to send their children to college. In the early 1900s, Blue Spruce’s parents had been forced into a federal boarding school to be assimilated into mainstream society. They wanted a better, freer life for their children.

Blue Spruce himself not only achieved such a life; he’s made it his mission to continue the dream of education for a new generation of American Indian dentists.

At the age of 90, Blue Spruce still works full time — as the assistant dean of American Indian affairs for A.T. Still University/Arizona’s School of Dentistry & Oral Health. His work is recruiting American Indians and Alaska natives to the field of dentistry.

One of his most effective means of recruitment has always been his life itself. He shares his story to inspire others. He wrote his autobiography to motivate students as they follow the path he cleared — a journey that began several decades prior, when a shy young man arrived at Creighton, the lone American Indian on campus.

* * *

Blue Spruce had no plans to become the first American Indian dentist in the U.S. In fact, he had no idea he would even be the first until a few years into his predental education at Creighton.

Blue Spruce became a dentist because of an act of kindness. This was in the late ’40s, when he was a teenager attending St. Michael’s High School in Santa Fe (where he graduated as valedictorian). Blue Spruce was participating in a bicycle derby when a man patted him on the shoulder and said, “I want to wish you good luck, George. I know you’ll do well.”

It might not seem like much, but to a shy and uncertain teen, those words meant everything. Blue Spruce later learned the man was a dentist, and from that moment on, his path was set. Blue Spruce would be a dentist, too.

His family asked the Christian Brothers at St. Michael’s where George should go to dental school, and they said his best option to get a great education and maintain his Christian beliefs was a Jesuit, Catholic university in Omaha, Nebraska.

“Once they made that recommendation, no other colleges were considered,” Blue Spruce says.

* * *

As the only American Indian student at Creighton, Blue Spruce felt like “a fish in a fishbowl.”

People were friendly enough. But he felt like a campus curiosity, an outsider. He said he could have died of loneliness that first year at Creighton.

He couldn’t afford to travel back home his first semester. On holidays, he was often the only student remaining in the residence halls. His first Thanksgiving alone consisted of going to see four movies and eating a meal of White Castle burgers and apple pie.

Even one of his college jobs was deeply solitary — nightwatchman for the medical school. (Checking the cadaver lab at night always spooked him.) He also worked two summers at Swift Packing House in South Omaha.

But things at Creighton gradually turned around for Blue Spruce. He started to make some good friends. He found mentors in his Jesuit professors. He was eventually elected class vice president and captain of the tennis team.

Tennis might have been the turning point for Blue Spruce. With tennis, he no longer felt seen as “just the lone American Indian on campus.” Now he was an athlete, the leader of a winning team.

“After a win, the Jesuits and students would say, ‘Nice going, George! We’re proud of you!’” Blue Spruce says. “I began to feel important because the people at Creighton were behind me. And I didn’t want to let them down.”

As he came out of his shell, he also felt a greater responsibility not to let down his family and community. He learned as much as he could about his tribe and American Indian history and culture in general.

“When people asked me questions, I didn’t want to put my heritage to shame by knowing nothing,” he says. “I owed that to the people back in New Mexico.”

After three years of pre-dental education, Blue Spruce was accepted into the School of Dentistry, taking one of 46 positions among 1,200 applicants. He earned the spot, he says, because he disciplined himself to work and study very hard.

During his first year of pre-dental studies, he was drafted into the Korean conflict but received a deferment. Later, when he was in his third year of dental school, he was offered a U.S. Navy commission to pay for the rest of his time at Creighton, so long as he committed to two years of payback service post-graduation.

That’s how he came to be Lieutenant Blue Spruce, USN, and provide dental care for enlisted men, high-ranking officers and the crew of the USS Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear submarine.

As a Navy dentist fresh out of school, Blue Spruce started to notice something. Other dentists — even ones more seasoned than him — were looking over his shoulder.

“I found out that many of the procedures and techniques I was taught at Creighton weren’t taught elsewhere,” he says. “People wanted to learn from me, and that gave me a lot of pride among fellow dentists.

“At Creighton, I felt I received the best training of any dental school in the nation. I learned to strive for perfection. And in my career, I never once deviated from the clinical excellence I was taught. Anything that fell short of the mark set by my Creighton instructors and the Jesuit priests would have been disappointing to my conscience.”

* * *

Blue Spruce ended up practicing dentistry just 11 years. He eventually shifted to administration after receiving his Master of Public Health degree from Berkeley in 1967.

His journey since Creighton has included many roles. He taught dental courses in every South American country except Paraguay. He served as director of dental services at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. He was the director of the programs that promoted social and economic self-sufficiency for all American Indian tribes, implementing the Native American Programs Act of 1974.

He served in the U.S. Public Health Service for 28 years and attained the rank of assistant surgeon general and director of the Indian Health Service Phoenix Area Office, serving the 42 tribes of Utah, Nevada and Arizona. He founded the Society of American Indian Dentists and served as its president for 16 years. He now holds the title of founder and president emeritus.

He tried retirement once. It didn’t take. After nearly 70 years, his life’s work still isn’t finished, he says.

“I have always been proud of what I was able to do at Creighton and what I’ve been able to do since. For what Creighton gave me, what they taught me, I am forever grateful.

“What I cherish most about Creighton is this: The University took the time and care to make me feel important. To make me know that I matter. In my career, I’ve tried to do the same for every patient, every student, every person I meet.”