Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

Something I picked up from Creighton that’s stayed with me ever since — the commitment to service and doing well for others. My wife and I love Creighton. We still have such a strong connection to the place.

Don't let me quit. Unless I'm seriously bleeding or I've broken a bone ... don't let me quit.

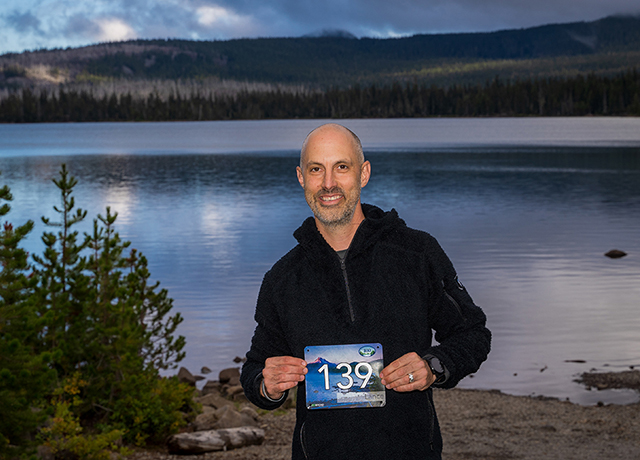

That's what Lance Cooper, DPT'04, told his wife, Ann Sprague, DPT'00, about a month before running his first 100-mile race. Ann promised him she wouldn't.

The day of the race — the Mountain Lakes course in Oregon's Cascade mountains — Lance rolled into the aid station at the 55-mile mark, and he was done.

Cold, dejected, demoralized, behind on time, bloody blisters on a field-dressed foot ... Done.

Ann was waiting for Lance at the aid station.

"I'm done," he told her.

"No you're not," she said.

Ann sat her husband down, got him some warm food and sent him off to finish the next 45 miles. And the next 45 miles felt great. Lance powered through the lull and made up for lost time.

To boost his morale, a few of Lance's friends — including his primary care physician — ran alongside him at different times for nearly every mile of the race. ("In racing and in life," Lance says, "you're only as good as your crew.")

He finished the course just shy of 28 hours. It was deeply satisfying, and in ways that only those who finish 100-mile races can understand.

But there was an extra layer to his accomplishment. A few months prior, doctors found a mass in Lance's brain. About a month before the race, a biopsy determined it to be a non-operable malignant tumor in his left parietal lobe.

And a few weeks after crossing the finish line, Lance would kick off months of radiation and chemotherapy — something far more torturous than any race he'd ever run.

* * *

Like most ultrarunners, Lance's passion had been a process of escalation.

About a decade back, he started running marathons. He gradually added miles, moving on to 50K races, then 50-milers and, finally, to the big 100.

Lance had already signed up for the Mountain Lakes race when he learned he had brain cancer. By that time the tumor was causing him headaches, fatigue and blurry vision. And yet, if anything, the bad news and its side effects only strengthened his runner's resolve.

"I had no idea what was going to be on the other end of this thing," he says. "If this was my last chance to run this race, to run any race, I had to do it. I knew I'd be kicking myself if I didn't finish what I started. And I believed I still could finish."

So did Ann. So did Lance's friends and family and physicians. And so Lance decided to run a 100-mile race after being diagnosed with brain cancer for the simple fact that he could.

But a more revealing question might be: Why run a 100-mile race at all?

Lance laughs. "That is the question. For me, it's because running an ultra doesn't just challenge your physical and mental capacities. It shows you who you are. You learn a lot about yourself on the trail."

There's nothing better than that feeling of the finish line, of working toward something extraordinary and achieving it. Lance also thrives on the logistics of tackling such long distances — negotiating with the blisters and parsing out the calories, rationing the toilet paper and determining the most strategic (and, hopefully, idyllic) spot for a bathroom break.

Like the man says: "You learn a lot about yourself on the trail."

* * *

Lance and Ann each run their own physical therapy practices in Ashland, Oregon. With the virus and social distancing measures, treatment has come to a halt.

Lance misses his patients. Helping others through physical therapy, he says, has been one of the joys and privileges of his life.

"That's something I picked up from Creighton, and it's stayed with me ever since: the commitment to service and doing well for others. Ann and I love Creighton. We still have such a strong connection to the place."

(Like so many Creighton couples, Ann and Lance were married at St. John's.)

Lance doesn't know when things will be able to get back to normal. For him. For anyone.

Appropriately enough, he's started looking at all this — his life, his cancer diagnosis, even the pandemic — like a race.

"Running a long race, you can't be worried about making it to the finish line. You've got to focus on making it the next four miles, to the next marker, the next aid station."

The longer the race, the more aid stations you'll hit along the way.

"Some of those aid stations will have warm food and all sorts of good stuff. Some of those aid stations will have nothing but chip crumbs and tap water.

"It's the same with everything else. Some days are going to be chip-crumbs-and-tap-water days. Those days are going to be hard. But you can get through them. You've just got to make it to the next checkpoint."

Lance is about to finish his final round of chemotherapy. After that, he'll get another MRI to see if the treatment has halted or slowed the tumor’s growth. He and his doctors will form a plan from there.

The days ahead are full of uncertainty. Lance and Ann don’t even know what the immediate future holds for them.

But they’re sure of at least one thing ...

Lance Cooper is not done.