Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

I can make plans, but I can also accept and maybe even embrace when things don’t go as planned.

By Micah Mertes

We can plan all we want, but we can’t predict the future, not as individuals and not as organizations, said Daniel Lawse, BA’02. And we especially can’t predict the future right now.

When it comes to policy, the economy, the markets, and every other one of the larger forces that shape our lives, careers and industries, “if we’re planning too far into the future, our plans are likely going to have to change,” Lawse said. If we want to not only survive but thrive, “we have to continually adapt to change. Which is, of course, the one constant in life.”

In 2009, Lawse (with Craig Moody) co-founded Verdis Group, an Omaha-based firm that helps companies and nonprofits across the U.S. identify and achieve their sustainability visions. Their resilience-focused approach to climate action planning and implementation is people-centered and driven by data, supporting partners with greenhouse gas emissions accounting, climate vulnerability assessments, decarbonization and reducing energy costs.

Every plan continues to be a living, evolving thing, said Lawse, a former pre-medical student who graduated with a degree in theology with an emphasis in justice and peace studies. The core elements of any good strategy are resilience and adaptability rather than miraculous foresight.

Over the past 16 years, Verdis Group has worked with more than 100 clients in various industries — zoos and aquariums, museums, healthcare, airports, education, financial and insurance institutions, architecture and engineering, cultural institutions, municipalities and more. Clients include:

- Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium. Verdis Group helped create the zoo’s first sustainability plan to conserve energy and water, reduce emissions and minimize waste. In addition to creating a healthier planet, the implemented changes save the zoo an estimated $800,000 annually. Since partnering with Nebraska’s No. 1 tourist attraction in 2012, Verdis Group has made zoo and aquarium sustainability one of its specialties, working with over 40 zoos and aquariums across the U.S., including clients in Seattle, Baltimore, Cincinnati, Denver, Monterey Bay and Dallas.

- First National Bank of Omaha. Since Verdis Group helped create FNBO’s Sustainability Master Plan in 2021, the bank has enhanced waste management systems, developed an electric vehicle plan and continues to reduce its carbon footprint at more than 100 buildings in eight states.

- Verdis Group has also worked with Nebraska Medicine, the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport, Omaha Public Schools, the City of Lincoln, Nebraska Methodist Health System, University of Nebraska at Omaha and more.

Learn more about Verdis Group’s clients and services here.

In 2023, Verdis Group became the ninth B Corporation in Nebraska (and the only sustainability consulting firm to receive the designation in the state). Companies with B Corp status meet high social and environmental performance and accountability standards. Compared to ordinary businesses, B Corps are much more likely to be carbon neutral, use renewable energy, conserve water and assess the environmental impact of their activities.

How Verdis Group does business and how Lawse lives his life takes inspiration from the resilience and adaptability of the very thing both are trying to save: the natural world—our common home.

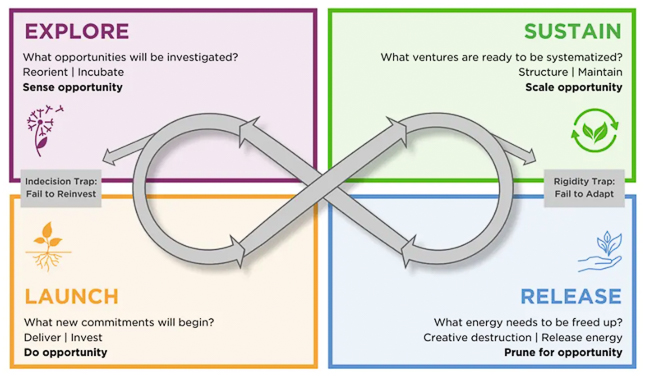

Lawse and his team subscribe to the living systems framework, which “emulates nature’s genius.” Lawse is especially partial to The Adaptive Cycle, a model of sustainability that helps individuals and organizations deal with and even take advantage of major changes in life and business by recognizing — to quote the American rock band Semisonic’s 1998 hit single “Closing Time” — that “every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end.”

The Adaptive Cycle is visually represented as an infinity symbol, reflecting the endless nature of change.

Lawse uses the example of a forest to illustrate the Adaptive Cycle’s never-ending feedback loop.

1. Sustain. “The forest is a stable, mature ecosystem. Of course, there’s death and little cycles contained within even this sustainability. But, for the most part, the forest is doing its thing, and the relationships are relatively stable. Then, change comes along.”

2. Release. “In this example, a forest fire destroys a lot of things. Animals are reduced to ash and trees to carbon; energy is transformed. With the tree canopy gone, sunlight is now hitting the forest floor, reaching long-dormant seeds and triggering release, nourished by the newly released carbon from the fire.”

3. Explore. “Some seeds fare better than others, insects and animal life returns, new arrangements emerge, new relationships are formed. This is the forest’s innovation phase.”

4. Launch. “This is the investment phase. Life is seeing what works post-forest fire. Some things thrive, others don’t. Some pioneer species that thrived in the exploration phase die out, creating conditions for new, more lasting species. Something like a new normal emerges, and the forest returns, full circle, to a period of stability.” (Until major change comes along once again.)

The Adaptive Cycle of the forest can be applied to just about anything big or small. In his own life, Lawse said, it gives him perspective when dealing with change, be it “good” change or “bad.” (“Most change is neither. It just is.”)

“Through this whole process, I don’t think nature is cursing and angry and depressed because the forest fire came through,” Lawse said. “Humans aren’t so lucky. We have emotions. We feel all sorts of big things when we feel the loss of what used to be: regret, rage, grief, frustration, despair.”

The point of the Adaptive Cycle isn’t to deny we emotional humans our period of mourning; it’s to help us accept that the world as we knew it has ended. Then to begin figuring out how to build anew. Just as some species give way to others during the adaptive cycle, our early emotions around loss can give way to feelings of hope and excitement for the new opportunities we’re discovering.

“Amid uncertainty and rapid change, this framework has helped me run my business and keep myself centered,” Lawse said. “I can make plans, but I can also accept and maybe even embrace when things don’t go as planned.”

How Lawse got to this point certainly wasn’t part of any grand plan—at least not on his part—but rather through a series of adaptive cycles.

Sustain. Lawse’s mother was a physician. He wanted to be one, too, and came to Creighton as a pre-medical student.

Release. Lawse realized during his freshman year that instead of going to medical school, he would rather focus on holistic health—on mind, body and spirit.

Explore. “But what kind of holistic health?” Lawse asked himself. “Do I want to focus on the mind with psychology? Or what about exercise science to focus on the human body? I tried different things, took different classes.” Experiences outside the classroom—retreats with Campus Ministry, working with the Schlegel Center for Service and Justice—guided his path. Lawse chose the spirit: a theology major.

Launch. In the theology department, Lawse gained a deeper understanding of what it means to be fully human. “The Jesuits have such a beautiful way of thinking about all of this.” He immersed himself in the core Ignatian values: caring for the whole person and living life for the greater glory of God. He learned how “to show up in the world and form a divine connection with the spirit.”

After graduating with a degree in theology (with an emphasis on justice and peace studies), Lawse tested a few different routes that he soon discovered weren’t for him: He started a theology master’s program at Creighton. (“But I decided I was done studying it. I wanted to live it.”). He might have become a Jesuit, but he’d already fallen in love with his future wife, fellow Creighton alumnus Andrea Comiskey Lawse, BA'02, MA'04. (Read more about Andrea, the founder of Artemis Tea & Botanical, here.)

“I was having a bit of an existential crisis,” Lawse said. “What do I do with this degree?”

Lawse had entered Creighton’s Christian Spirituality Program partly in the hopes of discovering his vocation. He found it in a class on environmental politics and policy.

“That class opened my eyes not only to the dysfunctional, exploitative relationship we humans have had with the planet recently but also to the opportunity we have to create a symbiotic relationship that could be sustained. Between my theology major and that class, my Creighton experience awakened something in me. I realized that I wanted to spend my life helping heal the relationship between humans and the Earth.”

Lawse attended the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he earned a master’s degree in community and regional planning, developing his own specialty in sustainable development and energy planning. After graduating, he promoted conservation as a council chair with Green Omaha Coalition and as the coordinator of sustainable practices at Metropolitan Community College. He also served as the board chair of the Regional Metropolitan Transit Authority of Omaha for several years.

Through these experiences and others, Lawse met Craig Moody, his future fellow co-founder of Verdis Group. Their first client was Omaha Public Schools, which asked them to find ways to save money through energy savings. Through their Energy Action Plan, Lawse and Moody identified millions of dollars of energy savings that OPS could achieve with a modest upfront investment.

OPS loved the plan, Lawse said, but they didn’t have anyone on staff to implement it. Would Lawse and Moody like to make it happen?

That was how a side gig became a full-time business. Verdis Group has since grown from two men in 2009 to 17 team members today.

“At Verdis Group,” Lawse said, “we invest in our team and our partners to help them live up to their missions and create conditions where everyone can thrive. We help them think differently so they can make the best decisions in the short and long term for themselves and for their communities.”

That’s not so different from the effect that Creighton University had on him, he said.

“Reflecting on my humanities degree and theology classes and Jesuit formation and everything that occurred at Creighton, I see now that I was given the opportunity to dive deeper into my life and my spirituality than most people will ever have the chance to.

“So much of who I am and how I think can be traced back to Creighton. It helped me find my way to where I am today.”

He never could have planned it.