Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

... but a dead rat under the floor drove him back to the Main Building.

By Micah Mertes

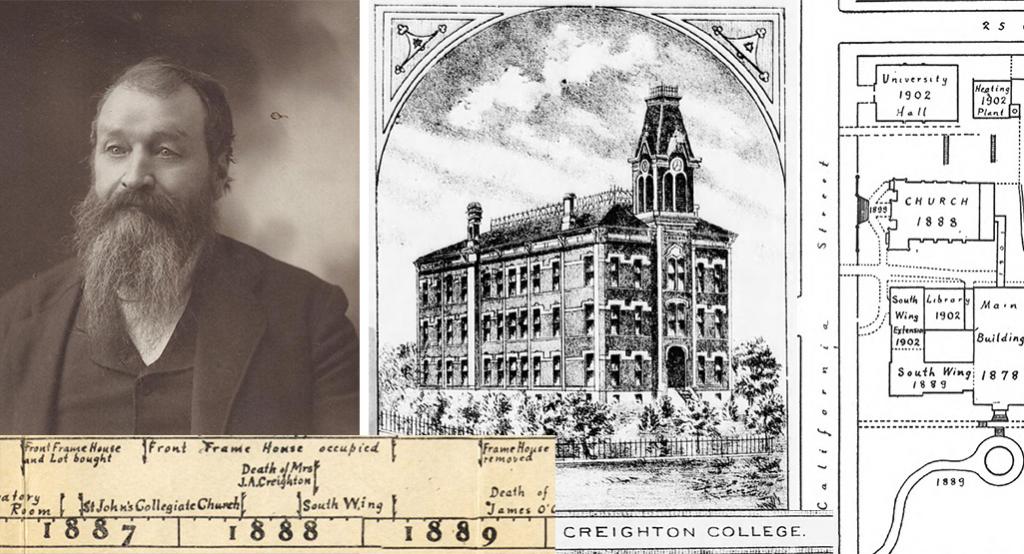

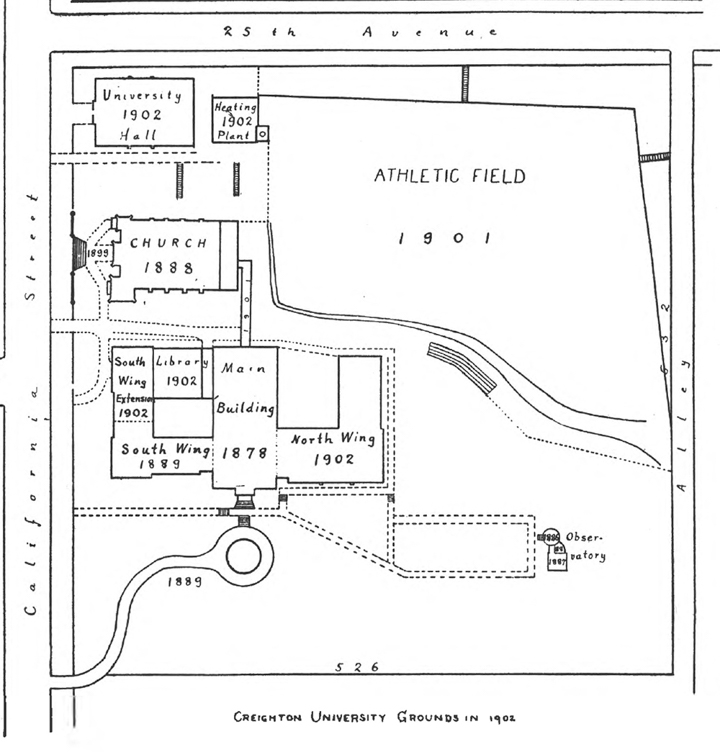

Today, Creighton University’s Omaha campus spans several blocks in every direction from its original 24th and California Streets core.

But in 1878, Creighton College (as it was then called) opened with a single building, and for years, that building stood next to a giant pile of manure that was part of a rotten negotiating tactic in a property dispute, the latest chapter in a long-running family feud.

This is the story of how a mountain of feces came to take up residence next to Creighton and how the matter was finally resolved.

A Sea of Mud

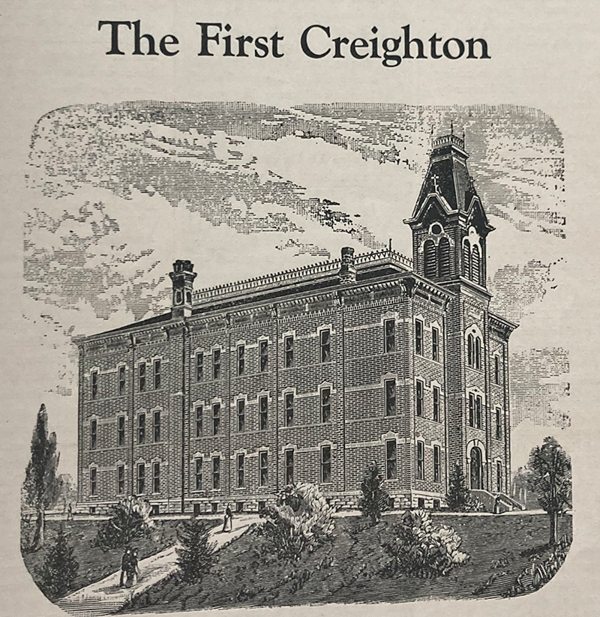

Nearly 150 years ago, the first part of Creighton Hall opened as Creighton College.

(The building has gone through a few names in the intervening years — the Main Building, the Administration Building and, finally, Creighton Hall, renamed in 2007 by then-President Rev. John P. Schlegel, SJ.)

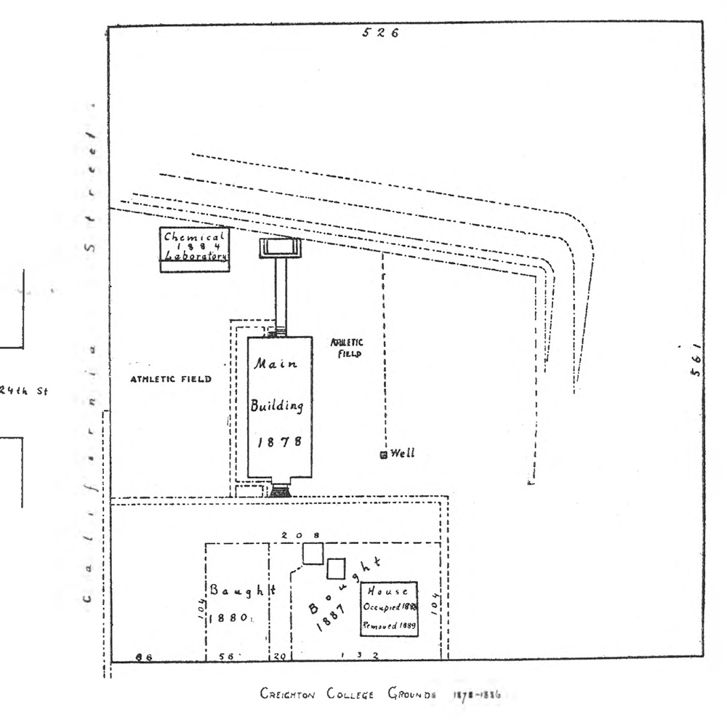

Creighton Hall stood on the brow of a hill sloping away to the east and north, the sole structure of campus grounds measuring just 526 by 561 feet. In its first decade, campus abutted just one street: California. At that time, no city streets were paved, making Omaha a big, sloppy mud pit for much of the year. The horse carriage journey from the train station to campus was reportedly an unpleasant one. Jesuits referred to the surrounding area as a “sea of mud.”

But this fetid backdrop made Creighton Hall shine all the more brightly. It was considered one of Omaha’s finest buildings.

In anticipation of 24th Street — expected to be one of the city’s busiest and most important thoroughfares — Creighton Hall was built to face east. (It would be another 32 years until 24th Street was opened up through campus.) Just 50 feet from the main entrance stood a horse stable and, a bit further, a large two-story house.

The house and stable were inconvenient to Creighton in several ways, the chief grievance being the four-foot fence that divided the properties. The fence created a dead-end alley for people traveling north to Creighton, and many students and guests would have to climb it to enter campus.

In his memoirs, Creighton’s renowned Jesuit astronomer Fr. William Rigge, SJ, called the property a “galling eyesore,” one the college wanted to remove as soon as possible. Fortunately, the property’s owner, a Mr. Reilly, wanted to sell the lot to Creighton. Unfortunately, he wanted too much money for it.

Reilly asked for $8,000. The college countered with $6,000. Talks stalled.

The college reportedly believed Reilly would cave soon enough, as he was exposed on three sides to “the pranks of noisy students.” But Creighton was mistaken, and it was a mistake that would cost the college and its founding family dearly.

Bad Blood

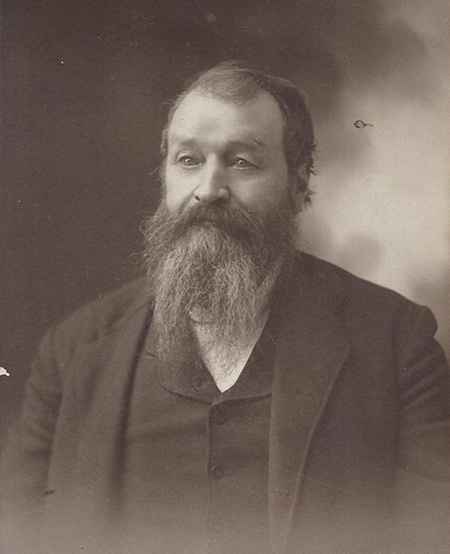

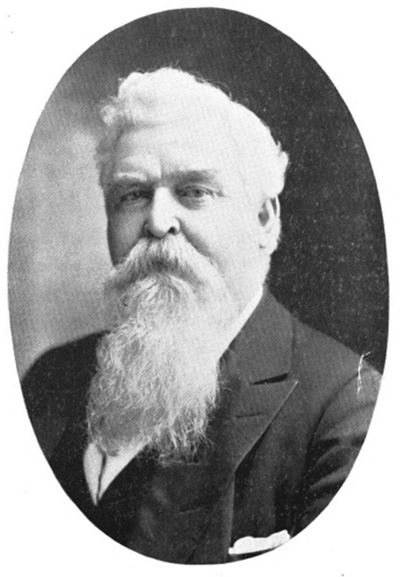

Enter John McCreary, the brother-in-law of Ed and John Creighton. There’s not a lot known about McCreary. He was born in Ohio. He made his fortune in railroad and telegraph line construction, broom manufacturing and other business ventures.

It was apparently through his work on the transcontinental telegraph line construction with the Creighton brothers that McCreary met and married their sister, Mary Creighton.

Like the Creighton brothers, McCreary was an Omaha pioneer — businessman, landowner and prominent figure in the community. His mansion on North 24th Street was one of the town’s premier homes. (According to an old newspaper story, the mansion nearly burned down when the hen the McCrearys kept in the kitchen knocked over a lamp.)

John McCreary and John Creighton did not get along. Later in their lives, there would be lawsuits and estate disputes between the families, but the igniting cause of their mutual animosity remains unclear. In any case, the vibes appeared to be bad from the start.

Back to the matter of the house and stable abutting Creighton Hall: The Jesuits and Mr. Reilly still hadn’t negotiated a sale. Seeing an opportunity to mess with his brother-in-law, McCreary swooped in and bought the property for the $8,000 Reilly requested. This would end up being a highly profitable move, not only in actual capital but in the priceless satisfaction that comes with infuriating your enemy.

The first Jesuit faculty kept daily logs from this time, so we have a play-by-play of how negotiations ensued.

In 1885, the Jesuits asked McCreary if he’d sell the property. He said he would … for $20,000 — more than twice what he paid for it. He also told the Jesuits that “there’s one man who ought to buy it for you,” referring to his brother-in-law, John Creighton.

The first outbound call from campus on record was to the home of John and Sarah Emily Creighton. Given the timing, the topic of discussion was likely the McCreary property.

Eventually, Creighton College President Fr. Dowling went to John Creighton to discuss the matter. For two hours, Dowling listened to “a catalog of grievances.” John Creighton refused to pay McCreary’s asking price.

The Jesuits went back to McCreary with a counteroffer. They told him Creighton College would name the new Observatory the “McCreary Observatory” if he gave them “his obnoxious house.”

From the Creighton Jesuits’ daily historical log: “McCreary did not answer but went out to his farm to evade us. He clutches his money bag and asks for his pound of flesh.”

Piling On

While McCreary awaited his pound of flesh, he hit upon a creative (and ultimately successful) negotiation tactic: allowing a large pile of animal manure to accumulate along the campus/farm property line.

This went on for years.

The stench tormented students and the Jesuit faculty to such a degree that, by 1887, all parties were ready to reenter negotiations.

After a bit of back and forth, John Creighton reluctantly exchanged a $15,000 property in downtown Omaha for McCreary’s lot. The college then paid McCreary an additional $2,000. In all, McCreary received more than twice what he’d paid for the lot a few years prior.

The barn was razed, the fence removed, the manure cleaned up and the animals moved elsewhere, but the house would remain a while longer.

At the time of the sale, the McCreary house still had a tenant — a Mr. Coburn, the sheriff of Douglas County. When his family’s lease was up a few months later, the college remodeled the house to be the first Jesuit residence external to Creighton Hall. (The Jesuits' living quarters have improved substantially in the intervening 138 years.)

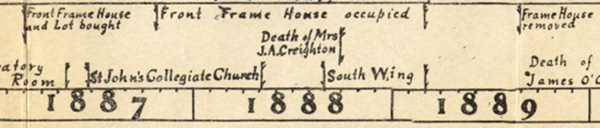

In 1887, this Jesuit Residence became the fourth campus building in Creighton’s history. (The second being the Chemistry Laboratory, a small building that once stood where St. John’s does now. And the third being the Observatory.)

The Jesuit residence didn’t appear to have an official name but was informally called the McCreary House. The Jesuits now had to live in a residence named after the man who for years bombarded them with noxious smells, who made them the collateral damage of his petty proxy war.

In a way, McCreary’s torment of the Jesuits was just beginning. Here are some highlights from the daily log during the Jesuits' first year in the McCreary House.

“Residence trembles in the storm. Fr. McGinnis reported his bed rocking like a hammock at sea.”

“Blizzard. Radiators out of order.”

“Mr. Donoher woke up chilled and with diarrhea.”

“Fr. O’Meara. Sick. Cold and fever.”

“Mr. Mara moved over to his little room in new Residence, but a dead rat under the floor drove him back to the Main Building.”

“Fr. Rigge (this would have been Joseph Rigge, William Rigge’s older brother), moved into the new residence yesterday. Got headaches from bad smell.”

“Fr. Rigge sick. Cannot teach.”

The next day: “Fr. Rigge moves back to college building.”

“Christmas day. Steam pipes burst in residence. Faculty suffering from cold invited to stay in college.”

Not all of Creighton’s Jesuits stayed in the McCreary house, but the ones living in the college didn’t have it much better.

Around this time, Sarah Emily Creighton, John Creighton’s wife, visited campus. She found the Jesuit living quarters primitive. She wanted better accommodations for the men leading Creighton College, so she and John gave $13,000 to add a south wing to Creighton Hall.

In 1889, the wing was completed and occupied by the Jesuit faculty and staff. The McCreary house was sold for $900 on the condition that it be removed immediately.

The home’s departure had finally brought the whole pungent drama to a close. Eventually, it also allowed for the long-delayed grading of 24th Street, during which workers unearthed a skeleton.

But that’s a story for another time. Suffice it to say that the remains were in no way related to the Creighton vs. McCreary feud.

Sources:

- The History of Creighton University, 1878–2003 by Dennis Mihelich

- Memoirs of Fr. William F. Rigge, SJ

- Historia Domas, Creighton University Archives and Special Collections

- Creighton University: Reminiscences of the First Twenty-Five Years by Fr. Michael P. Dowling, SJ

- "A History of North Omaha's McCreary mansion," NorthOmahaHistory.com

- Newspapers.com, Omaha Daily Bee

- Omaha Illustrated: A History of the Pioneer Period and the Omaha of Today