Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

Creighton and its health partners are leaders in blending interprofessional collaborative practice with interprofessional education. We’re lucky to have a University and clinic partners who support this work and vision. It takes faith and courage to do something this different.

Austin Nider, OTD’19, remembers the aha! moment. It happened on his student rotation at the University Campus family practice clinic, when a woman came in with hand pain.

The physician ordered an X-ray, which showed a tendon fracture, something an earlier trip to the emergency room had missed. During her X-ray, the patient said her injury was the result of domestic violence. The clinic called in the behavioral health team to meet with her about her options. The patient then needed a recovery timeline. Physical and occupational therapists were on hand to help.

“In the span of about 30 minutes and one patient visit, we had three or four different disciplines in the room taking care of this person,” says Nider, who is now an inpatient occupational therapist at CHI Health Creighton University Medical Center–Bergan Mercy. “We asked our colleagues for help, and there they were.”

Nider says he saw such teamwork play out on a daily basis at Creighton. But that moment was the first time he really understood the power of collaborative care — the health care model used at CHI Health Creighton University Medical Center–University Campus.

Also called interprofessional collaborative practice, it operates on a few core principles: Health care is a team effort; and clinicians working together (closely, honestly, efficiently) leads to better patient care — lowering costs, improving outcomes, saving lives. The underlying idea is this: No. More. Silos.

Not in the clinic and not in the classroom.

Collaborative care brings together the whole team of health care professionals, drawing on all disciplines to treat the patient from every angle. It represents, its advocates say, the future of clinical care.

“It’s everyone under the same roof, everyone truly integrated,” says Thomas Guck, PhD, psychologist and professor in family medicine at Creighton. “We’re bringing all our resources to bear to serve the patient in a seamless way. In the end, it improves health outcomes and saves money for the patient.”

He’s got proof.

Guck was the lead author of a study published this summer in The Annals of Family Medicine. The study — conducted at the University Campus outpatient clinic and led by the College of Nursing, the School of Medicine and the Center for Interprofessional Practice, Education and Research (CIPER) — looked at patients receiving high-volume care and how their outcomes and costs changed during the first year they were treated with the team-based, collaborative approach.

The results were striking: More than 16% fewer emergency room visits; nearly 18% fewer hospitalizations; a near-50% reduction in patient charges; and more than $4 million in annual savings at the clinic.

The study used a three-tiered plan to build the model: staff and clinician training, patient care preparation and care conference planning (i.e., different disciplines meeting to talk about patients). Staff also trained in conflict resolution.

Research on the efficacy of collaborative care dates back decades. More than 80 trials have shown collaborative care to be more effective than ordinary care, according to the University of Washington’s AIMS Center. Many of the studies centered on mental health. One paper found that patients with depression who received collaborative care were much less likely to have a cardiovascular event. In 2016, the American Psychiatric Association and the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine released a report calling for the advancement of the collaborative care model.

There are more studies to come, Guck says. He and his partners will soon publish the findings of four years and multiple cohorts worth of data. They hope to show that the first study’s results can be replicated and sustained.

The results, Guck says, address the triple aim associated with U.S. health care reform, as outlined by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement: 1) Improve the patient experience; 2) Improve the health of populations; and 3) Reduce the per capita cost of health care.

To better achieve these aims at the University Campus clinic, Guck says, staff regularly repeat a few mantras: “We are all learners. We are all teachers. We all assume positive intent.”

The way it used to be, a patient might see a physician here and a physical therapist there, and they often never talked or even knew about each other, let alone the specifics of their shared patient’s care.

Collaborative care rejects that way of doing things because it’s no longer feasible.

“As a country, we’re spending more money for poorer patient outcomes,” Guck says. “Something’s got to give here.”

Health care costs continue to grow, with insurance fees rising at a faster rate than wages or inflation. Life expectancy, meanwhile, has declined in the U.S. for the past three years in a row, a trend not seen since the influenza pandemic of 1918.

To face these crises, Guck says, health care must shift its pay system to a value-based model, in which providers are reimbursed not for individual visits or services but a patient’s overall health outcomes. The model incentivizes providers: The healthier the patient, the more a provider earns.

There are examples of this already underway.

North Carolina is moving away from the fee-for-service model to a system in which providers are paid based on outcomes — managing a heart patient’s cholesterol, for instance, or a diabetes patient’s blood sugar. The effort is supported by the state’s Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees payments for Medicaid and Blue Cross Blue Shield, which together account for about two-thirds of the state’s insured population, reports The New York Times.

Health insurers such as UnitedHealth Group, Cigna and Aetna, meanwhile, are shifting more than half of their reimbursement to value-based models.

Advocates say the move to outcomes-based pay will, in turn, save patients money and make them healthier, something that aligns ideally with the whole person-focused practice of collaborative care.

The idea for savings is simple — collaborative care offers a one-stop shop for all of your health care needs, reduces the number of visits and procedures, improves your overall health and, ultimately, relieves the burden on your wallet.

Cost savings, as much as anything, are driving the need for new health care models, says Joy Doll, OTD’03, an occupational therapist, director of Creighton’s Center for Interprofessional Practice, Education and Research (CIPER), and one of the study’s authors.

“We know we have to do something about the cost of care,” she says. “We know we have to look at new models. We love the collaborative care model because it helps us be more efficient. It gives patients access to the right care at the right time.”

The first step in all of this, of course, is giving students access to the right education at the right time.

When it comes to training students in the collaborative care model, “Creighton is leading the way,” says Amy McGaha, MD, professor and chair of family medicine at Creighton, and director of the Interprofessional Clinical Learning Environment in CIPER.

“Creighton and its health partners are leaders in blending interprofessional collaborative practice with interprofessional education,” says McGaha, who also holds the Dr. Roland L. Kleeberger Endowed Chair in the School of Medicine. “You’ll find a lot of institutions doing one but not the other. We’re lucky to have a University and clinic partners who support this work and vision. It takes faith and courage to do something this different.”

And to be sure, the collaborative care model is quite different. At one point, health sciences education was just as siloed as clinical practice used to be. Students were secluded to their own specialties, says Catherine Todero, PhD, BSN’72, vice provost of Health Sciences Campuses and dean of the College of Nursing.

“We taught students how to be nurses and doctors and pharmacists,” she says. “But we didn’t teach them how to work together in teams for the good of the patient.”

That’s changed at Creighton, she says. Now the different professions are talking. Sometimes disagreeing. Sometimes having different, even competing goals for a patient. Figuring out how to reconcile those goals and work through those disagreements, Todero says, that’s what a collaborative care education is all about — learning how to talk to each other productively.

In this age of efficiency, optimized modes of work and communication are of course sought after in every corner of the economy. But at a clinic, the stakes are higher. When health care professionals aren’t effectively communicating, the patient suffers.

“The quality of communication improves the quality of care,” says School of Medicine Dean Robert “Bo” Dunlay, MD’81. “Our students learn this over the full course of their training. It’s not just something taught here or there. It’s part of who they become.”

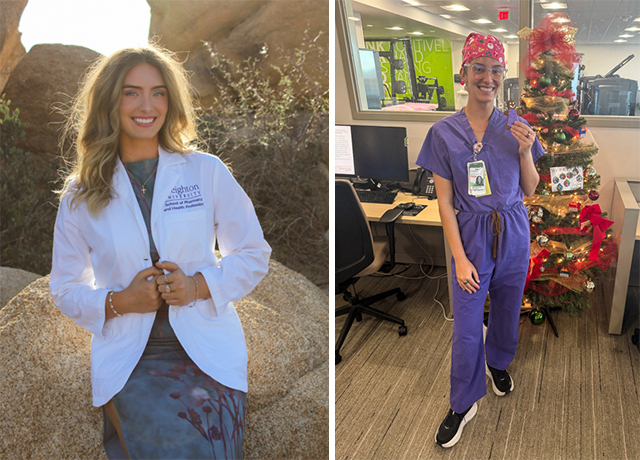

That’s true for Meredith Chaput, DPT’18. She worked a rotation at the University Campus clinic as the collaborative care model was being implemented. Now she’s doing a physical therapy athletics residency at Vanderbilt University.

Fittingly enough, she uses a sports metaphor to describe collaborative care. The model is, she says, a group of solo athletes learning how to be team players.

“Traditional medicine can get stuck in a hierarchy,” she says. “But in collaborative care, everyone’s on a more equal footing.”

That requires humility and selflessness, she says. And that starts in the classroom.

One example of collaborative care in the classroom is Creighton’s head and neck clinic for dental and medical students. Taught by ear, nose and throat/head and neck cancer surgeon Thomas Dobleman, MD, the clinic focuses on identifying cancers.

“I tell dentists that they’re on the front lines of discovering head and neck cancers,” Dobleman says. “In the clinic, I show the students that by adding 15 seconds to their exams (and knowing all the causes of head and neck cancer), they can save lives.”

He tells the students not only to look for cavities and cracked teeth but also check for thyroid masses, melanomas and throat cancer (the fastest-rising cancer in the U.S.). If a dentist, or any health care professional, is too focused on their own specialty, they might just miss something vital.

“Sometimes it’s as simple as noticing something and calling someone,” Dobleman says. “Hey, I’ve got this patient, and I want to hear what you think … .”

This might seem obvious, but these barriers are just now breaking down, he says. It’s not how he was trained. It’s not how most clinicians were trained. Everyone’s catching up, and Creighton is catching up faster than most.

It makes sense that the University is taking the lead in this health care model, Dobleman says. Collaborative care speaks to one of Creighton’s core values.

“The University prides itself on treating the whole person,” he says. “But we’re seeing that it often takes a team of people to treat a whole person. We have to do this together.”

On the surface, collaborative care isn’t always as dramatic a shift as some patients might expect.

“Patients will wonder, ‘Am I going into this clinic where 20 people are waiting to take care of me?’” says Meghan Walker Potthoff, PhD, BSN’01, an associate professor in the College of Nursing who co-wrote and helped secure funding for the study. “No. The difference is taking place behind the scenes, where the team is working together and looking at your health goals from every angle.”

And there’s another thing going on behind the scenes at a collaborative care clinic, a happy side effect, if you will: Clinicians are feeling better, too.

Out of 151 CHI Health clinics, the University Campus clinic’s staff used to rank in the bottom third for employee engagement and job satisfaction. Since collaborative care was adopted, the clinic ranks as one of the happiest to work at.

Boosted morale means higher retention means stronger bonds, stronger teamwork, better care for all.

All the pieces, working together.