Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

Beal’s is the only place you can go to get food and verbal abuse.

Read more: Alumni serve up their Beal's memories

* * *

Note: Sources for this story include the Creightonian, the Omaha World-Herald, the Bluejay yearbook, Creighton magazine, the Alumnews and, of course, the University Archives and Special Collections, which makes all features like this possible.

By Micah Mertes

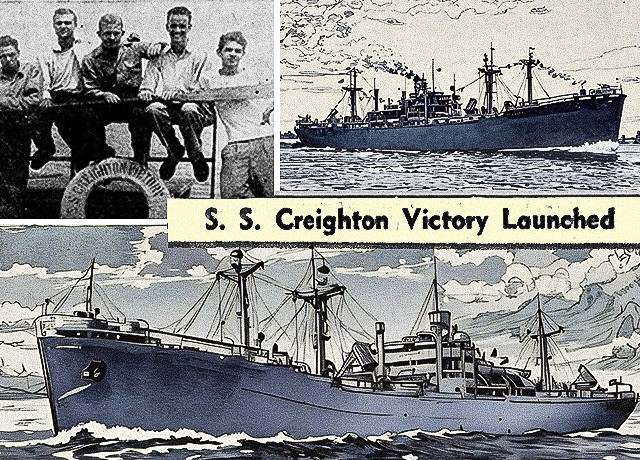

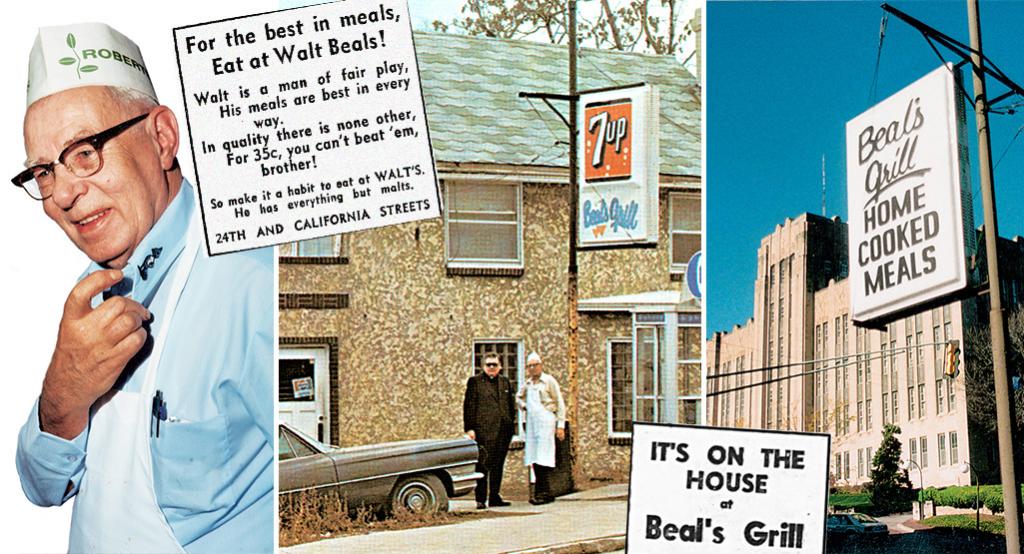

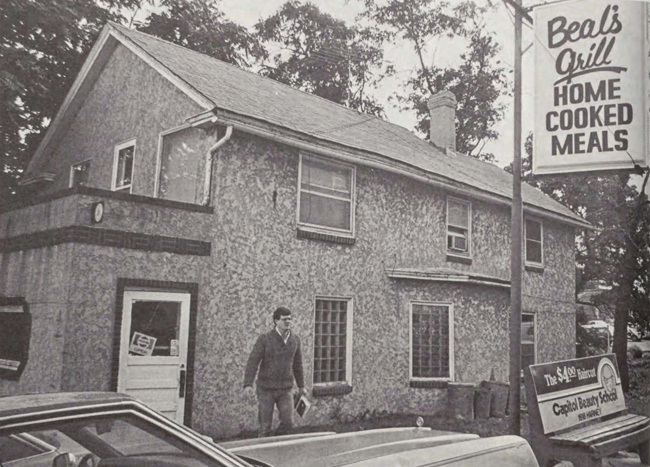

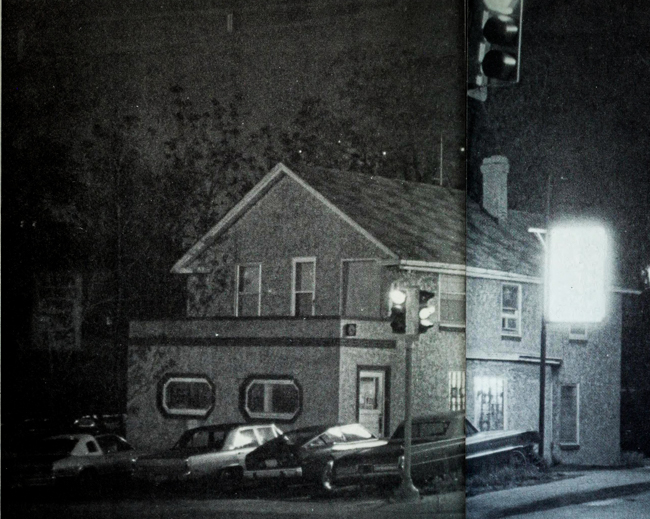

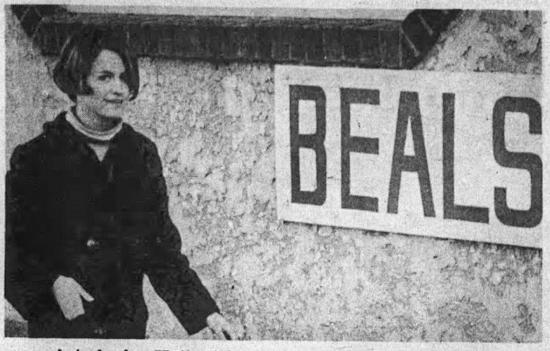

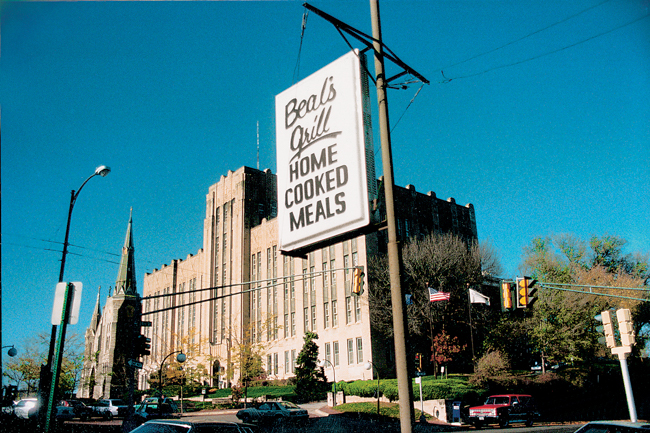

Before Beal’s Grill was Beal’s Grill — the beloved dive at the southeast corner of 24th and California that for nearly 50 years served burgers, fries and insults to thousands of Creighton students, faculty and staff — it was a two-story stucco home where a gruff man with a soft heart lived with his wife.

The legend (which has a few variations depending on the source) goes like this …

‘I think I’ll make this house a restaurant’

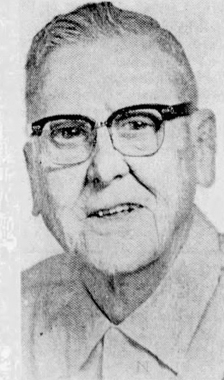

One afternoon in 1939, Walt Beal looked out his upstairs window and across 24th Street to Creighton’s campus.

This was in the waning years of the Depression, and Walt was an unemployed ex-traveling salesman who needed a new way to earn a living. As he looked out upon Creighton Hall and St. John’s Church and watched the many students go about their daily business, he noticed that most of them were leaving campus to grab meals elsewhere when lunchtime came around.

Walt pointed at Creighton and looked over to his wife Hazel and daughter Burnice (Beal) Fiedler — whose husband, Howard Fiedler, would later run the restaurant. Walt let his thoughts take shape aloud:

“I wonder if those boys are hungry … Shall we starve to death or shall we see if they’re hungry? … I think I’ll make this house a restaurant.”

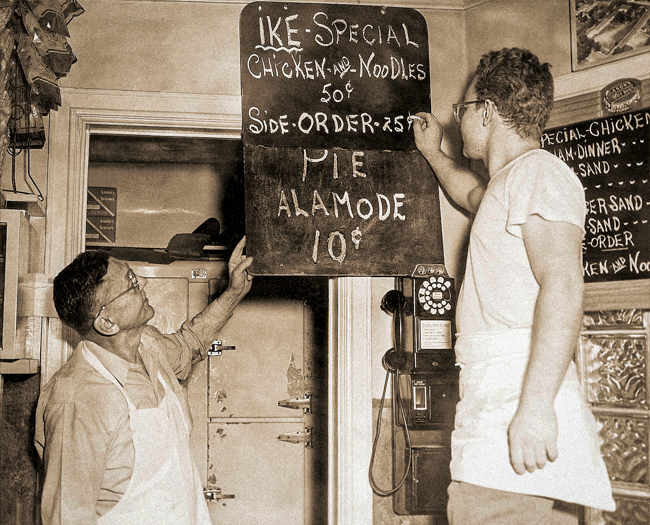

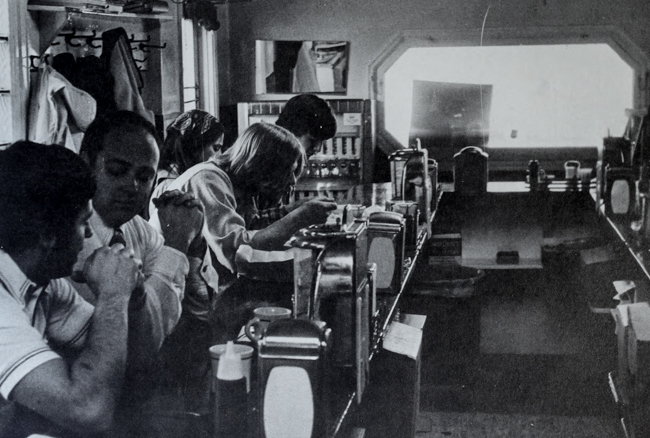

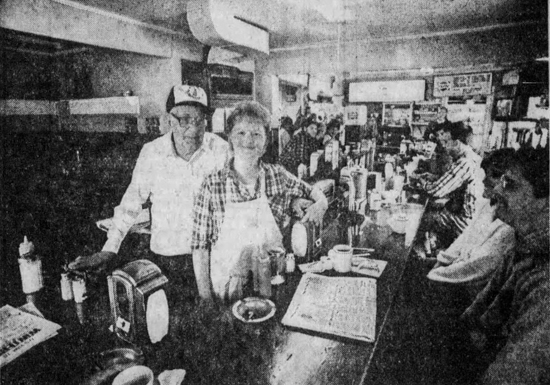

Walt wasted no time making his idea a reality. He moved himself and Hazel upstairs, tore out the first-floor living and dining rooms and filled the space with a grill and a horseshoe-shaped counter lined with two dozen spinning stools with red vinyl seats. Walt later added jukebox selectors, pinball machines, a separate dining room for professional students and (in 1950, to much fanfare) a television set.

Most alumni who ate at Beal’s will recall its green counter. But, according to an old Creighton magazine account, it was actually blue, perhaps to go with Creighton’s primary color. Over time, the buildup of grease, cigarette smoke and profanity had apparently given the linoleum a greenish hue. (Like much else regarding Beal’s, I can’t 100% confirm this is true, but it’s too funny a detail and too perfect a metaphor to leave out.)

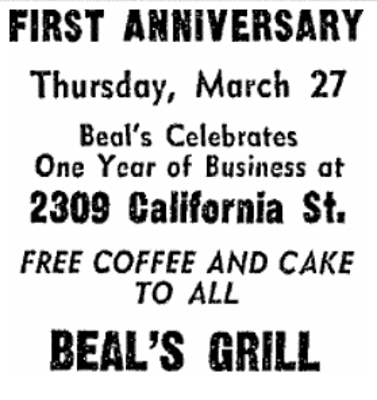

Before Beal’s opened in 1940, Creighton already had an eatery — Wareham Hall’s Beanery — but Walt surmised (correctly) that students would welcome an alternative.

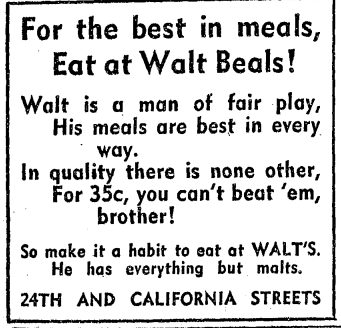

Beal’s prices were just right for cash-strapped students. Two donuts and a cup of coffee were 5 cents, two pork chops were a quarter, and a small T-bone with a side of fries ran 35 cents.

BealBurgers and fries were the more popular items, but each day, the menu featured everything from the breakfast staples of pancakes, eggs and bacon to snarky specials like “Sewer Trout,” “Sow Belly” and “Floor-Sweepings Pie.”

For the next 46 years — 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Monday through Saturday — Beal’s Grill was a cornerstone of campus life, the place you went for first-hand gossip and secondhand coffee (more on that shortly).

At its height, Beal’s served home-cooked meals to 900 people a day. The space would often get so crowded that lines formed behind each stool, with waiting guests haranguing the seated eaters to hurry up and finish their meals (or cigarettes).

Walt once estimated that 90% of his customers came from Creighton. He knew most of them personally.

“I know all these kids,” Walt once told the Creightonian. “I even like some of them.”

* * *

“Beal’s is the only place you can go to get food and verbal abuse.”

— Kim Bean, BA’87, told the Creightonian in 1986

* * *

The Walt Beal era (1940-1958)

5 things that reportedly happened at Beal’s during this time

1. Due to Walt’s colorful language and rough attitude, Creighton’s dean of women at one time forbade all female students from entering Beal’s Grill on threat of expulsion, making the restaurant a males-only establishment in its early years.

2. Walt once got into an argument with an officer from Creighton’s ROTC department, who then declared Beal’s off-limits to all ROTC students. The officer’s replacement later rescinded the order.

3. Walt loved nothing more than to bet on horses. He even raised his own thoroughbreds. One day at the Ak-sar-ben track, one of his horses died in the middle of a race. The next day at Beal’s, several customers made wisecracks at Walt’s (and his poor horse’s) expense. Walt’s ghoulish retort: What meat do you think you’re eating right now?

4. Walt was known to cut corners in creative ways. One method was repeatedly pouring the cold dregs of his own coffee back into the steel urn to be served to his customers. An early instance of student-focused sustainability.

5. A medical student, perhaps running late to class, once shouted an order to Walt: “Two eggs over in a hurry!” Walt calmly grabbed two raw eggs, walked over to the student and splattered them onto his shirt. Walt then handed him $5 and told him to get himself cleaned up.

That was the thing about Walt. He often took things too far, but he at least apologized afterward. In his own peculiar way.

'Terse and pungent'

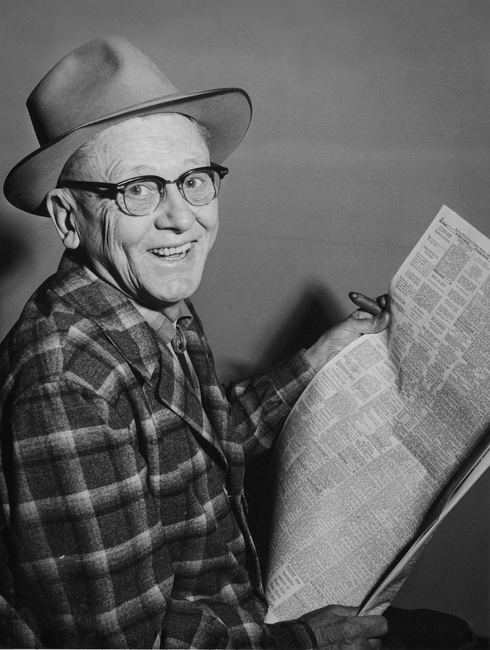

When Creighton students walked into Beal’s at any given time of day, they would find the proprietor in one of two places: behind the grill or sitting on his stool at the south end of the counter, drinking a coffee, smoking a cigar and reading the newspaper. (Woe to anyone who took Walt’s stool.)

Walt (and later his son-in-law Howard) greeted regulars not with their actual names but the nicknames he’d given them: “Council Bluffs,” “Red” and “John Hancock,” a student known for signing his name on napkin IOUs when he couldn’t cover his meal. That was another telling trait of Walt’s: Sure, he never turned down the chance to mock anyone, but he would also, often at the same time, do them a kindness, like waiving their bill.

Walt had more general nicknames for students from Creighton’s various professional schools. If a law student, medical student, pharmacy student or dental student walked through the door, Walt would holler, respectively, “Liar!”; “Body Wrecker!”; “Pill Pusher!” or “Mouth Plumber!” (Howard later continued this tradition of profession-based epithets.)

Though Beal’s didn’t serve alcohol, many of the old stories make the cafe sound like an R-rated Cheers, only if Ted Danson’s Sam were older, meaner and spent most of his spare time betting on horses. The sitcom version of Beal’s would, of course, be called Jeers. (“Where everybody knows you’re lame.”)

All this disdain was playful and (underneath it all, to some degree, maybe) loving. The grill’s crusty charms weren’t for everyone, but if you acquired a taste for it — its harsh words, its caustic owner, its napkin-soaking burgers — it was hard to eat anywhere but Beal’s.

One of the first people to work with Walt was the Rev. Neil Cahill, BS’43, MS’77, a Creighton student in 1940 and later a Jesuit and economics professor at the business college. Fr. Cahill — a Hilltop legend in his own right — paid his way through Creighton working behind the Beal’s counter, “slinging hash” for 25 cents an hour.

Even when he wasn’t working, Fr. Cahill would stop by Beal’s at all hours, sometimes drinking coffee late into the evening and exchanging barbs and banter with Walt.

“Terse and pungent.” That was how Fr. Cahill described Walt 33 years later while delivering the sermon at the latter’s funeral in 1973 at St. John’s Church. (The Beal family wasn’t Catholic, though they always made sure the restaurant served fish on Fridays during Lent.)

However Walt acted, Fr. Cahill said, "the Old Man loved Creighton. And the alumni felt the same.”

* * *

“One morning about 3 a.m., we heard a dog yelp out there on 24th Street. It had been hit by a streetcar. Walt got up, put the dog in his Cadillac and drove to the vet. He pounded on the vet’s door, woke him up and told him to take care of this animal and send him the bill.”

— Burnice Fiedler, Walt’s daughter, told Creighton magazine in 1997

* * *

The two sides of Walt Beal

Beneath the insults, the verbal tirades and the surly demeanor, behind this man who, as the Creightonian liked to report, often “woke up on the wrong side of the grill” was another Walt Beal. One who cared for animals. Who loaned students money. Who, in his own way, took an active interest in his friends, neighbors and customers.

If students were short on cash, Walt let them run up a tab. (“Well, you’ve got to eat. Bring it when you’ve got it.”) He gave part-time jobs or made loans (often unpaid) to students who’d fallen on hard times and needed help with tuition or living expenses. Though Walt hadn’t finished high school himself (expelled due to bad behavior), he valued higher education and wanted his customers to make something of themselves.

His aid sometimes came at a cost. Walt’s daughter, Burnice, recalled the time a financially strapped student came into the restaurant to ask for a loan.

“The student told dad he just had a new baby and didn’t have any money. Walt was calling him every name in the world and saying, ‘You’ve got the guts to come in here and ask me for money when your father could buy me and sell me?’ And all the time, my dad was counting out $250 to give to the student.”

Walt was most dedicated to Creighton’s student-athletes. He and Hazel were die-hard Bluejay fans, attending as many home and away games as they could for Creighton basketball and (before the program was canceled during WWII) football.

Walt sponsored the home games’ radio broadcasts. He gave all student-athletes discounted meals. The evening before a big game, he would close the restaurant a bit early and feed the whole football or basketball team for free. He was even known a time or two to bail a few Creighton athletes out of jail on his own dime.

Walt was close friends with Olympian boxer Carl Vinciquerra; Creighton basketball hall-of-famer Donald “Pinky” Knowles, JD’51; and Johnny Knolla, BS’46, Creighton hall of fame football player and NFL halfback. Walt and Knolla were so close that the latter helped out at the grill from time to time.

Every year, Walt took a long summer vacation, usually closing Beal’s until the students returned for the fall semester. (Walt actually ran a second Beal’s Grill location at his vacation destination of Lake Okoboji, Iowa, whenever he spent summers there.)

One summer, Creighton’s enrollment was so high that Walt didn’t want to close Beal’s for those three months. Johnny Knolla — who had, mind you, recently played in the NFL before serving in the U.S. Army during WWII — was back at Creighton working on his education degree. He agreed to keep Beal’s running until Walt returned.

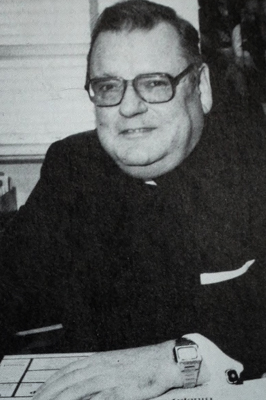

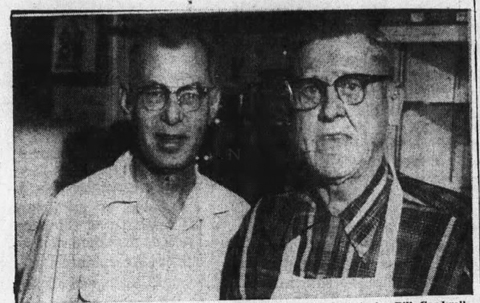

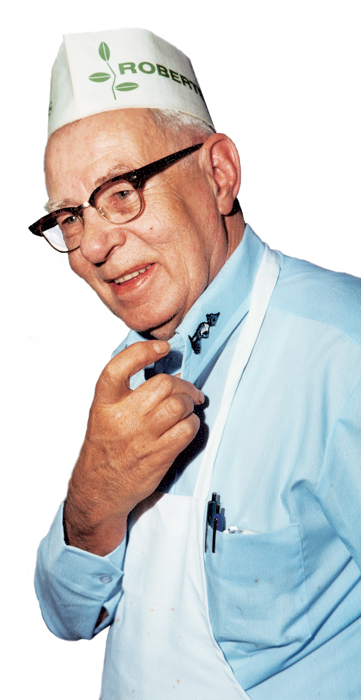

Walt “retired” in 1958, passing the torch (or, rather, the spatula) to his son-in-law Howard Fiedler, though Walt stuck around the grill for many years after. Sometimes he put on an apron and helped out when the crowds picked up and they were short-staffed. Or he’d sit at his stool greeting/harassing regulars as they walked in.

A few years into his semi-retired tenure as proprietor emeritus, Walt told the Creightonian that he saw Creighton as his “big brother.” The University had always looked out for him and helped him and his family earn a living. It introduced him to countless friends now living all over the world.

(When he wasn’t running the Beal’s Okoboji summer site, Walt was known to take long trips elsewhere. One year, he took a six-week vacation to Hawaii. When his ship docked in Honolulu, he was greeted by the entire Hawaiian branch of the Creighton Alumni Association, many of them one-time Beal’s Grill regulars.)

Fr. Cahill said that wherever you went, Beal’s was on the minds of alumni.

In 1973, at Walt’s funeral, Fr. Cahill said that he had traveled to hundreds of alumni events around the country, and the first questions anyone asked him were almost always …

Whatever happened to Beal’s? Is it still there?

“The family has really done something for Creighton over the years,” Fr. Cahill said.

* * *

“Once, when I complained that my food was cold, Walt walked to the counter, stuck his finger in my macaroni and cheese, nodded his head in agreement and then provided me with a fresh, hot meal.”

— T.Q. Smith, BA’67, told Creighton magazine in 1997

* * *

The Howard Fiedler era (1958-1986)

5 things that just made Beal’s Beal’s

1. “We never really cleaned the grill,” John Foley, BSBA’78, said in 2004. Foley worked at Beal’s from 1975 to 1978. “Luckily, I don’t think there was any sort of health inspection at the time.”

2. The grill was a good luck charm to many. “Eating lunch at Beal’s on the day of MCATs (Medical College Admission Tests) or DATs (Dental Admission Tests) is a good luck tradition,” Ray Harre, MD, BS’80, said in 1979. (As you can see by the MD next to his name, Harre passed his MCAT, going on to earn his medical degree from the University of Iowa.)

3. In 1997, alum John Kilbride, MD’63, recalled an incident when he was a student eating breakfast at Beal’s. When one of Kilbride’s friends cut into his pancake, he found a Band-Aid inside. A few seconds later, the grill’s cook, Ziggy, came into the dining area, “turning his index finger back and forth, looking for something that was missing.”

4. The pinball machines were a popular attraction at Beal’s, with a handful of students playing them nonstop. One was Aaron Salem, a College of Arts and Sciences student in the late ’70s. Salem was the reigning Beal’s pinball champ for years. He would return every night just to make sure no one had beaten his score that day. If someone had, Howard would let Salem play for hours after close to make sure he could reclaim the high score.

5. Beal’s inspired poetry. Tony Oreskovich, DDS’88, wrote “Memory Grill” when he was a Creighton dental student:

Memory Grill

The usual menu —

Burgers and fries;

Somedays a Special,

Always improvised.

Lunch counter service,

Not enough spinning stools.

Indigestion, congestion,

Final exam fuel.

Counter-top jukebox —

The same forty-fives;

Four years at Beal’s

And time passed it by.

Progress needs parking,

A leveled lunch spot;

More spaces, more cars

On a memory lot.

* * *

“We may joke around and throw jibes across the counter, but it’s never serious. You can say anything to the students, and they don’t get mad. They just ignore it and come back the next day for more.”

— Howard Fiedler

* * *

Serve yourself

The following anecdote comes from a 1984 article in the Omaha World-Herald:

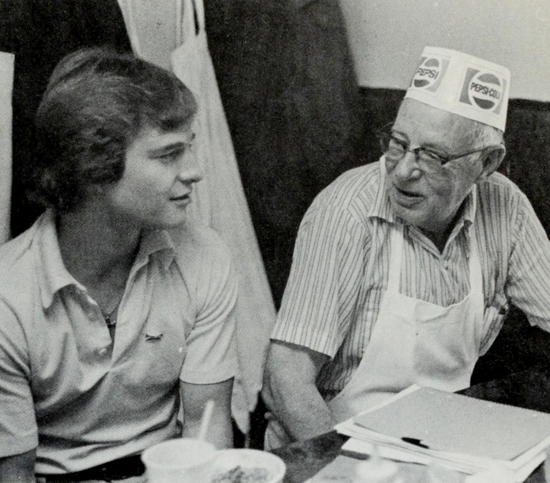

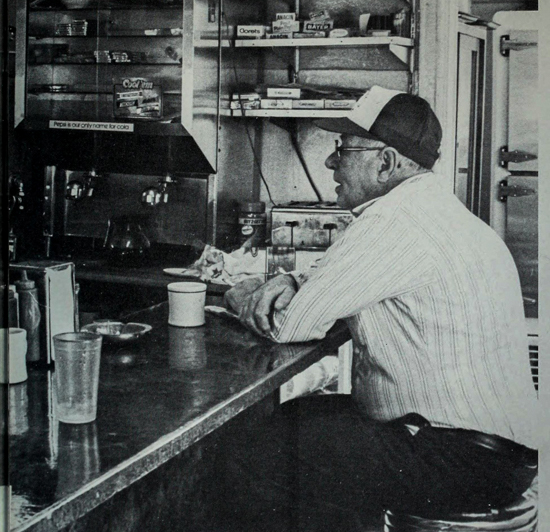

In 1984, just a few years before Beal’s closed for good, Howard Fiedler — the proprietor of Beal’s since 1958, who took full ownership when Walt died in 1973 — sat at the horseshoe-shaped counter, on the same stool Walt had, drinking his coffee, smoking his cigarette, reading his newspaper.

“Hey, Howard! How about some coffee down here?” a student shouted.

“I’m busy. Get it yourself,” Howard said, a few feet from the coffeemaker.

The student walked over to the coffeemaker and poured himself a cup. Other students sitting around the counter called for coffee as well, turning the first student into an ad hoc Beal’s server. Soon, the whole café started jokingly calling for coffee orders.

“Not,” Howard said, “until I’ve finished the paper.”

Regulars at Beal’s usually helped themselves to donuts or toast or coffee behind the counter. “You get the best service by waiting on yourself,” Howard liked to say.

Howard idolized his father-in-law and did everything he could to carry on Walt’s legacy. Little had changed at Beal’s over the years except for the prices, which were still quite low by the 1980s (80 cents for a bowl of Howard’s famous chili; 85 cents for a Jumbo BealBurger; less than a dollar for a “genuinely cold” milkshake).

The cheap, greasy, hearty food. The cutting conversation. The owner who knew most of his customers personally and often floated them loans or waived their tabs. All of this remained on the menu.

(Beal’s even had its own legacy families. Some Creighton students who worked for Howard were the sons of Creighton alumni who worked for Walt.)

Yet Howard did have one shortcoming in his attempt to be just like Walt.

“Howard tried to emulate the Old Man,” Burnice Fiedler told the Alumnews in 1986. “But he couldn’t. He is just too nice.

“My father and my husband are entirely different personalities. Walt was a crusty old character. Howard is such a nice man. Both were kidders, but Howard carried it out in a kinder way.”

Case in point: Remember the anecdote about Walt splattering two raw eggs onto a student’s shirt when he asked for “two eggs in a hurry”?

Many years later, a student shouted a similar order to Howard. Howard repeated Walt’s bit but in a gentler way. He simply placed the raw eggs on the counter and smiled at the student. The same lively, mischievous humor but with none of the mess.

Nothing lasts forever

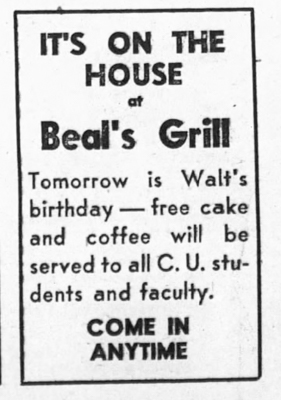

Another Beal’s tradition Howard kept up was the birthday celebration. Starting in the 1940s, Walt would order a 30-pound cake from Omar Bakery every year for his Dec. 13 birthday, throwing a party with free cake and coffee for everyone who could squeeze into the café.

After Walt died, Howard continued the tradition, holding the party on his own Oct. 13 birthday. For a few of Howard’s parties in the 1980s, his longtime friend Eddie Butler performed live music.

Butler was a Council Bluffs-born organist who played for 22 years at Omaha’s Orpheum Theater and, starting in 1934, at St. John’s Church on Sunday mornings. Butler was nationally renowned, having performed for two popes and five Presidents: Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy. And, also, Howard Fiedler.

“Something different happens here every day, so it’s never boring,” Howard told The World-Herald in 1984. “As for the Jesuits and administrators at Creighton, we consider them our very good friends.”

Howard said that the Creighton students themselves had changed over the years. “But they have one thing in common. They are good kids. Sure, once in a while a bad apple comes along, but it’s rare, I’ll tell you that.

"I’ve loved every minute of the many years I’ve been with this grill.”

Many of his customers felt the same. Students went to Beal’s for many reasons, “but most of all you went there to see Howard,” said Joe Scranton, JD’77, in a 1999 Creightonian article.

Howard wasn’t just the cook. He was the in-house advice columnist on seemingly every topic, whether you wanted his advice or not. He was the grill’s self-designated philosopher, sneaking life lessons into his never-ending stream of taunts. A few kernels of wisdom could be distilled as:

No one can serve you better than you can serve yourself.

Don’t take yourself (or anything else) too seriously.

Nothing lasts forever so savor every meal.

When Howard was on bed rest recovering from a heart attack in 1984, he said what he missed most was joking around with the students. Who else would keep them in line if he wasn’t around?

Howard died at the age of 83 in 1996, 10 years after Beal’s had closed. Services were held at St. John’s. Burnice Fiedler followed her husband in 2004. Memorials were dedicated to the Beal’s Grill Scholarship Fund she had established.

Beyond their own lifetimes, the family wanted nothing more than to keep serving Creighton students.

* * *

“I don’t know if I can live without this place.”

— Howard Fiedler, on the day Beal’s closed, Nov. 15, 1986

* * *

Closing time

The day before Beal’s closed for good in the fall of ’86, Fr. Cahill stopped in for breakfast. It was so busy that Howard gave the Jesuit an apron and told him to take and serve orders. More than 40 years since he first started “slinging hash,” Fr. Cahill was behind the counter again. “It was almost like old times,” Fr. Cahill said.

In its final week, Beal’s saw crowds it hadn’t seen in years. Howard said the number of Beal’s customers had dipped in the last decade, as more students started to own cars and could pursue more distant dining destinations. Beal's had had a good run, he said. It was time.

“I’ve seen a lot of faces come and go through that door,” Howard said. “But we can’t keep it up forever.”

Beal’s was the last business along 24th Street to close, making way for Creighton’s campus expansion. Creighton never pressured Beal’s to sell, Burnice Fiedler said. But her father had given his word that the property would eventually go to the University.

On Beal’s last day, longtime waitress Zonia Nazaruk (known to customers as “Z”) said goodbye to the students.

“I had it made here,” Z said. “I’m going to miss all these kids. I don’t have any kids of my own, so I kind of call these kids my kids. They give me a hard time, but I like it.

“The students always called Beal’s a ‘grease pit’ or a ‘dive.’ But the food can’t be all that bad. They kept coming back!”

On closing day, many alumni who had heard the news that Beal’s was closing stopped by for one last meal, one last chance to run their hand across the countertop, one final opportunity to be insulted by Howard.

At 7 p.m., Beal’s closed, the crowd said goodbye, and Howard perched on his special stool to look around and take stock …

The framed Beal’s newspaper articles or Creighton team photos from over the years tacked to the café’s walls.

The refrigerator door covered with decades of postcards from students and alumni, signed with old nicknames like “Just another body wrecker” or “The Liar.”

Countless memories of students with a BealBurger in one hand, pouring over their books or chatting with friends.

Somewhere around here, Howard wondered aloud, was a dirty magazine that someone once exchanged for a meal many years ago. He’d have to find that before the Beal’s inventory auction the following week.

Finally, Howard slid off his stool, put on his coat, turned off the lights and flipped the sign to "Closed." He looked back at the counter one last time.

“Every time I look, I think I see someone sitting there.”

* * *

Read more: Alumni serve up their Beal's memories

Dessert: More Beal's goodies before you go

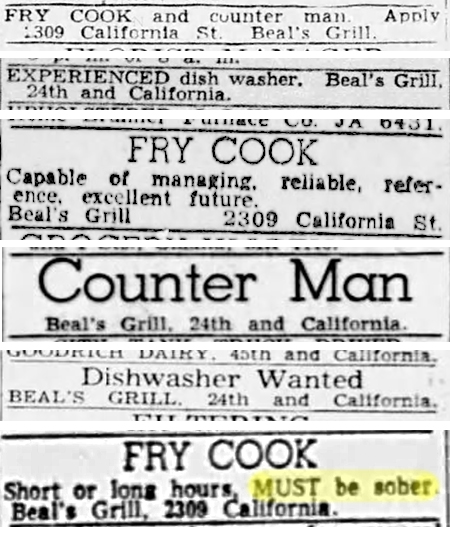

Different Beal's classified ads that ran in the Omaha World-Herald in the 1940s and 1950s:

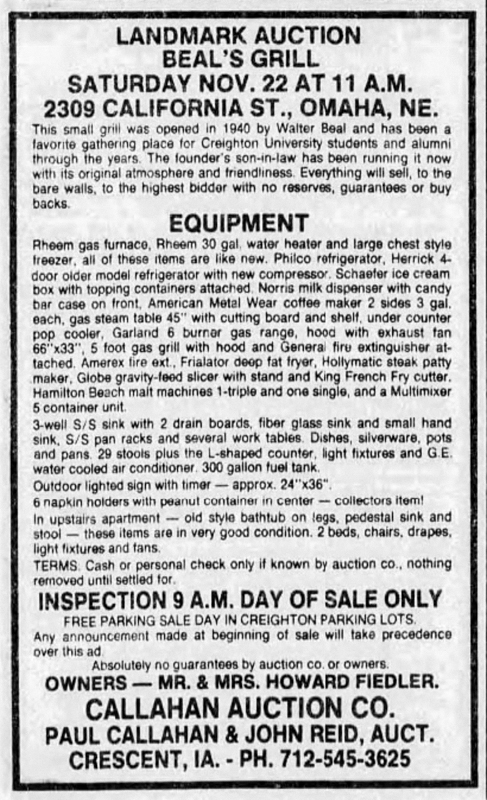

A list of the inventory at the Beal's auction held in Nov. 1986:

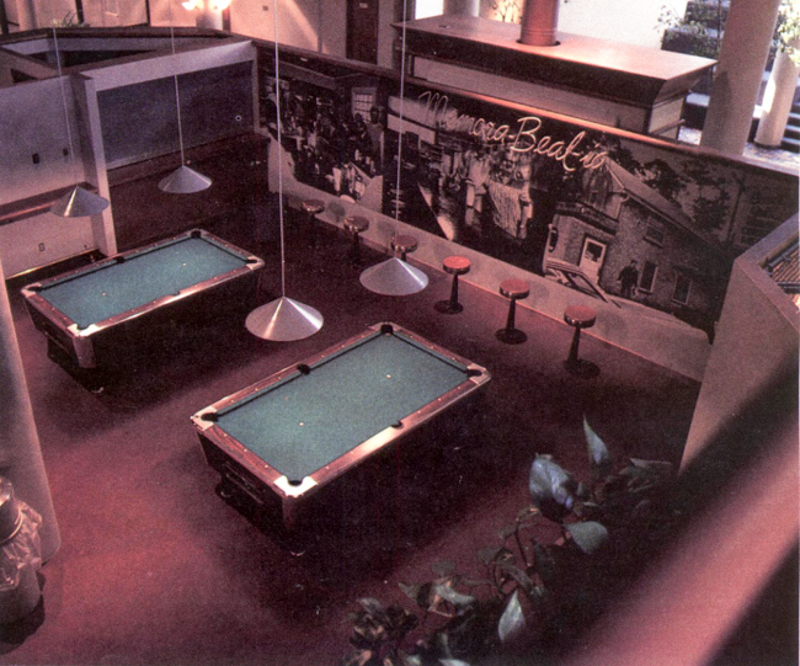

In the late '80s, Creighton installed half a dozen of the original stools and a "Memora-Beal-ia" photo mural in the Skutt Student Center:

Beal's handed out commemorative wooden nickels each year for its anniversary. Reportedly, none were ever cashed in.