Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

If I got hit by a truck, the New York Daily News would say, ‘Batman Producer Killed.'

By Micah Mertes

This month, Robert Pattinson becomes the ninth actor to play the Caped Crusader on the big screen in The Batman, the superhero’s 13th live-action, feature-length film.

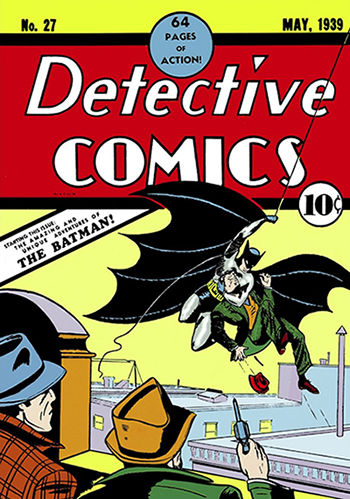

Since Bob Kane and Bill Finger created him 1939, Batman has become one of the most well-known and iconic characters in all of fiction (as well as one of the most profitable; did we mention this is his 13th movie?). Batman has remained so enduringly popular for so long that most have forgotten just how close he came to oblivion.

By the 1960s, the character was on life support. His adventures had grown silly and strange, and fans were losing interest. His comic sales were so poor, in fact, that “(DC Comics) was planning to kill Batman off altogether,” Bob Kane once said.

(In the melodramatic voice of a cliffhanger ending): Was this the end for Batman?!

It was not. Thanks largely to one man.

The savior of Batman was an unlikely one — a man who had never read a comic book, who in fact disdained the medium when he paid attention to it at all.

Yet the man sensed untapped potential in a worn-out character. He saw an ever-so-narrow path forward. He would save Batman by making fun of him.

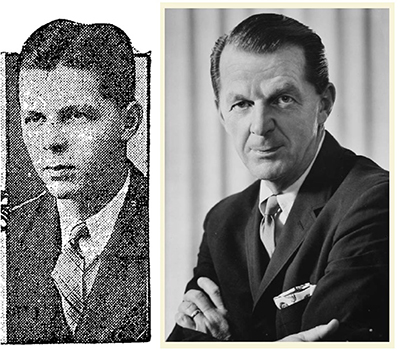

Our hero’s identity? Creighton alumnus and Omaha native William Dozier, Law’31, PhB’32, creator of ABC’s Batman TV series (1966-68).

* * *

Please enjoy this short commercial break! This article is brought to you by … fact-checking! There is some discrepancy in our records about when Dozier graduated. Other sources show him graduating from the College of Arts and Sciences in 1929 (studying history and philosophy) and obtaining his law degree, or at least studying law, elsewhere. In any case, he IS a Creighton alum, but aspects of his origin story remain mysterious.

Now, back to the show!

* * *

Our hero once thought he wanted to be a Jesuit.

Shortly after graduating from Creighton Prep in 1925, William Dozier entered the Jesuit novitiate in Florissant, Missouri. He soon returned home to attend Creighton University.

“I came home because I fully realized that my life’s work is not along those lines,” the College of Arts and Science freshman told the Creightonian upon his return.

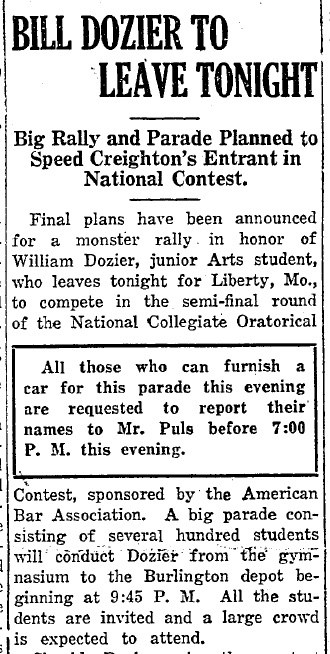

The school newspaper continually referred to Dozier as a “prominent student.” His terrific voice and speaking abilities made him the star of the University’s debate and oratory teams. As a junior, Dozier competed in the National Collegiate Oratorical Contest. The honor was considered so great that the University held a rally and parade just for him.

After graduation, Dozier tried his hand at real estate, but the economic crash soon forced him to pivot. Like so many young men, he headed west.

Dozier started his career in Hollywood as a talent agent for writers (a job he supposedly acquired by happenstance one day while golfing). He had a few superstars for clients: Erle Stanley Gardner, Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, to name a few. He was soon recognized for his fine storytelling instincts and, in particular, his talent for selling stories.

Dozier eventually set his sights on Hollywood’s chief export. He quickly rose through the ranks of various studios. He would go on to work for RKO Radio Pictures, and later to serve as the head of Paramount Pictures’ story and writing department. He would run the TV arm of Columbia Pictures and lead CBS’s west coast office. (The Los Angeles Times once referred to Dozier as “having worn more titles than a silent movie.”)

During his tenure, he oversaw such TV series at Perry Mason, Gunsmoke and The Twilight Zone, and such movies as Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious.

But, as Dozier himself once predicted, much of his legacy would fade away in the face of his most famous accomplishment.

“If I got hit by a truck,” Dozier once said, “the New York Daily News would say, ‘Batman Producer Killed.’”

* * *

By the ’60s, DC Comics (or, rather, its precursor National Periodical Publications) had seen tanking sales across the board, and ABC was able to buy the TV and film rights to Batman for a song — just $7,000.

To produce the show, ABC called on 20th Century Fox and Greenway Productions, a new company formed by a certain Creighton alum.

When the project landed on Dozier’s desk, he thought his fellow executives were “out of their minds.” How could such a project be successful?

But then the man who had never read a comic book gave it a little more thought. Dozier did his research, buying a dozen comics to read on a flight to LA. The experience only increased his bafflement. This was “ridiculous and ancient basic material,” he would later say.

“I knew kids would go for the derring-do, the adventure,” Dozier once said. “But the trick would be to find adults who would either watch it with their kids or watch it anyway.”

That’s when the idea hit. He would “do the show so square and so serious and so cliché-ridden and so overdone, and yet with a certain elegance and style. It would be so corny and so bad that it would be funny.”

It was, as it would happen, perfect timing for a bright, garish, tongue-in-cheek TV series about a man dressed as a bat.

It was, as it would happen, perfect timing for a bright, garish, tongue-in-cheek TV series about a man dressed as a bat.

By 1966, Pop Art was at its peak. Hipster irony was in the air. Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein had recently blown up comic strip panels into gallery-wall art. American TV viewers were ready for something new, weird.

Dozier hated the word “camp,” yet in the Batman TV series he created, he would realize its ultimate embodiment.

* * *

Batman debuted on ABC on Jan. 12, 1966. It was an instant phenomenon, quickly becoming one of the top 10 most watched shows on TV, with 30 million viewers per episode.

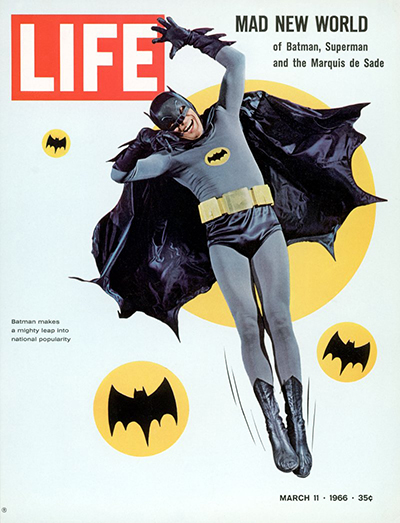

“Bat-mania” not only saved ABC’s flagging ratings; it boosted DC’s comic book sales and revived the character’s diminished brand overnight. The hero himself even made the cover of LIFE magazine.

Batman was also an early merchandising juggernaut, raking in tens of millions of dollars on toys, clothing and novelty items.

Kids, adults and even critics, for the most part, loved the show. The only ones who seemed to hate it, really, were fans of the Batman comics. And when you think about it, writes Glen Weldon in The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture, that’s pretty funny in itself.

Weldon writes: “The abiding irony that hardcore fans decry the show for ‘not taking Batman seriously’ lies in the fact that ‘taking Batman seriously’ was precisely the show's organizing principle.

“The particular genius of the show's approach, and the key to its mass appeal, was this tonal jujitsu. They reproduced the conventions of the era’s one-dimensional Batman comics in three dimensions and asserted them with a species of terrible, poker-faced gravity. In so doing, they achieved something that television, let alone the culture, had never seen before.”

Batman ended up being exactly the show Dozier envisioned — “a sitcom without a laugh track” — thanks in no small part to a few terrific collaborators.

Lorenzo Semple Jr. — a screenwriter who would go on to help pen the classic conspiracy thrillers The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor — wrote the first season’s zany scripts.

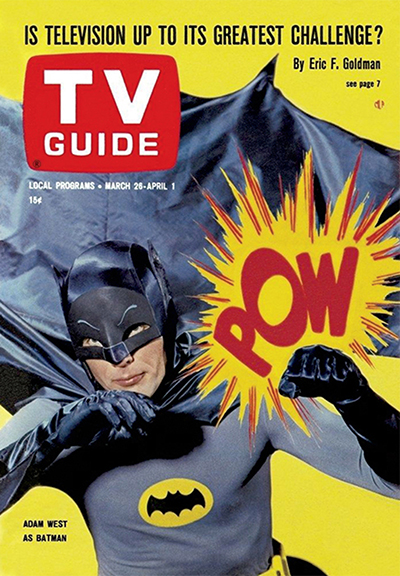

Meanwhile, stars Adam West and Burt Ward nailed the show’s intended tone to perfection — particularly West, who played the character as serious as possible. West internalized Dozier’s creative credo: “If they see us winking, it’s dead.”

(Read about the time Adam West came to Creighton dressed as Batman.)

Batman spared no expense — its first episode cost a then-outrageous $500,000 to produce — with the candy-colored sets, props and costumes living up to Dozier’s go-big-or-go-home ethos. (Amusingly enough, the show got a fairly rotten response from test audiences, but ABC had already agreed to multiple episodes before the pilot aired.)

As promised, Batman worked on two levels: fun for the kids, funny for adults.

The public’s reaction to the show is wonderfully captured in a Feb. 1966 Creightonian article — “Batitis infects students, no quick cure foreseen” — which covered the “Bat-mania” sweeping campus. Each week at Creighton, a crowd of students would gather in front of the Student Center lobby’s TV set more than an hour before the new Batman episode started.

“Some campus addicts,” the article reads, “see Batman as pure nostalgia for the good old peanut-butter sandwich and comic book days; some view the show as idiotic. All agree it’s harmless.”

One student said, “It’s an insult to my intelligence. That’s why I like it.”

An English professor had less qualified praise: “It is so obviously a caricature of pop comics, a great form of satire.”

Anyone who watched the show (in its original run or its many years of syndication) remembers the “POW!” and “BAM!” sound effects superimposed onto the screen during fight scenes. And how the camera tilted askew whenever the Joker, Penguin or Catwoman (Cesar Romero, Burgess Meredith, Julie Newmar) took center stage. And who could forget the show’s impossibly catchy and iconic surf-rock theme song?

The Batman theme, an ear-wormy guitar hook composed by Neal Hefti, is regarded as one of the best of all time, inspiring a few great artists along the way.

If “Bat-mania” was obviously a fad, it was one that had wings. That first year, Batman was nominated for the Emmy Award for outstanding comedy series (losing to The Dick Van Dyke Show).

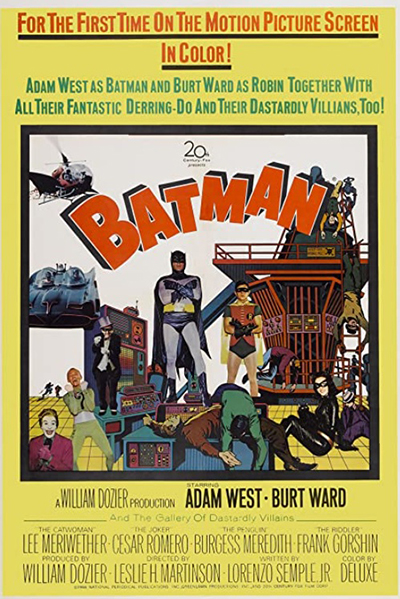

Ahead of its second season, Dozier and 20th Century Fox rushed a Batman movie into production. The first feature-length Batman movie hit theaters in the summer of 1966 and played like a very long, very special episode of the series.

It was a box office failure, spelling the end of “Bat-mania.”

* * *

This article will conclude after a short commercial break! The 1966 Batman wasn’t the first time the character had been translated to the screen. The show and movie were preceded by two different Batman serials (in 1943 and 1949), with actors Lewis Wilson and Robert Lowery filling out the cape and cowl, respectively. But the 1966 Batman movie was the among the first feature-length superhero movies to reach the big screen, and the very first in color.

* * *

Much like the old movie serials that influenced it, the Batman TV show usually ended on a cliffhanger. In the show’s first two seasons, ABC would run half-hour episodes every Wednesday and Thursday, ending the former episode on a moment of nail-biting suspense.

Each episode was bookended with a narrator either catching the audience up or teasing the next episode. The narration was as over-the-top and tongue-in-cheek as every other part of the show. Every syllable had two exclamation points.

Over time, each Tuesday episode would end with the narrator’s catchphrase, “Tune in tomorrow! Same Bat-time, same Bat-channel!”

Here, if you’re so inclined, are 22 minutes of Batman cliffhangers.

The show’s narrator was uncredited, referred to only as “Desmond Doomsday.” His secret identity? Former award-winning Creighton orator William Dozier.

Dozier said in an interview that he became the narrator by accident.

While cutting together Batman promotional reels for ABC, he filled in as makeshift narrator until they could hire someone. But when he showed the reels to ABC, the execs asked, “Who’s that narrator? We have to get him signed for series.”

After the Batman movie disappointed at the box office, Dozier saw that “Bat-mania” was on the wane. The series would last another two seasons, for a total of three, ending in 1968.

When the World-Herald interviewed him in 1968, on the heels of Batman’s cancellation, he shrugged it off:

“Well, we had a good three-year run. That’s not bad for what was essentially a novelty show. You’ve got to be realistic about such series. But I suspect that Batman will go on playing forever.”

He was correct. And then some.

Though short-lived in its original run, the series has continued playing in syndication all over the world for decades. And in 2014, Batman was finally released on home video after a long legal battle.

The 1966 series’ breadth of influence on the history of comic book culture is debatable, but its immediate impact can’t be denied, with the show’s success quickly kicking off a wave of other superhero TV shows and movies.

Dozier himself produced the Green Hornet series, which introduced most American audiences to Bruce Lee. (Dozier and Lee met after a martial arts tournament.) Dozier also made a pilot for an ill-fated Wonder Woman sitcom.

In the coming decades, the studios would make the first truly successful superhero movies, 1978’s Superman and 1989’s Batman. Though each were much different tonally from Dozier’s creation, one could credibly argue Batman (1966) crawled so these later films (and perhaps the whole superhero movie industrial complex) could fly.

After the rise and fall of Batman, Dozier gradually withdrew from show business. He became a book reviewer. He taught drama and public speaking at Mount St. Mary’s College in LA. He did continue to act in films and TV occasionally, but his producing days were behind him.

Despite his many fascinating experiences, Dozier chose never to write his memoirs. (“If I was truthful, I’d have to leave town,” he once said.) Dozier did, however, donate a huge collection of his papers to the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center, which contains a vast array of materials relating to Hollywood history.

The Dozier collection includes thousands of documents, including hundreds of correspondences that show just how at the dead center of things Dozier was. There are letters between Dozier and — to name just a few — Bruce Lee, Adam West, fellow Omaha natives Marlon Brando and Fred Astaire, Dick Clark, Rod Serling, Elmore Leonard, Steve McQueen, Warren Beatty, Ronald Reagan, Angela Lansbury, Henry Kissinger and Lucille Ball.

Among all those stars and world leaders, there’s one correspondence that stands out, from Carl M. Reinert, SJ, former president of Creighton University.

Dozier — who died in 1991 — never forgot his roots, continually returning to Omaha and even occasionally helping out with the Aksarben Ball. Even at the peak of his success, his Midwestern modesty won out.

Here’s Dozier with the final word:

“There’s a great deal of luck in show business. Luck in timing, luck in being able to get the right people at just the right time. You can think successfully, but if you don’t have a big sprinkling of luck, you are in big trouble in the entertainment business.”

* * *

Stories like this wouldn’t be possible without the help of the University Archives, the keeper of Creighton’s history. Please consider making a gift to the Archives and helping us preserve Creighton’s amazing story for generations to come.

* * *

Sources:

University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center

American Heritage Center Heritage Highlights

The Creightonian

Omaha World-Herald

Batman TV show turns 50, The Nation

Nationally Distinguished Nebraskans, E. A. Kral

William Dozier obituaries: Variety and the LA Times

Why we’re just now getting the 1960s Batman TV show on DVD, Wired magazine

Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon by Will Brooker

The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture by Glen Weldon