Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

The case in which I was involved was the real thing. I had no doubt about it then, and I have no doubt about it now.

By Micah Mertes

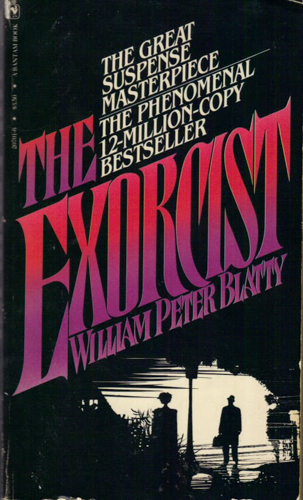

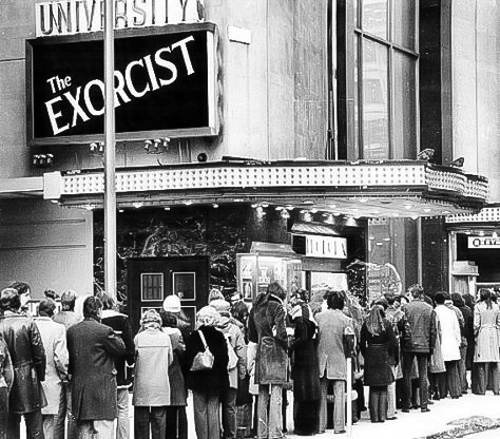

A little more than 50 years have passed since its release, but The Exorcist is still the most popular and acclaimed and (by consensus) scariest horror movie of all time.

It remains the ninth highest-grossing movie of any genre (adjusted for inflation). It was the first horror movie to be nominated for Best Picture. Its script, adapted by William Peter Blatty from his bestselling novel of the same name, won the Academy Award for best screenplay.

Many people who have read or seen The Exorcist know the book and movie were based on the account of a real incident: the exorcism of a 13-year-old boy in St. Louis. Few know that three Jesuits leading the exorcism had strong ties to Creighton. One was the brother of a Creighton University president. One was later a Creighton professor. The third later worked in Creighton's Alumni Relations division.

Here's the story of the real-life exorcism that inspired the movie and the Jesuits who led it.

* * *

A note about the sources: The primary source is a 29-page diary one of the Jesuits kept of the exorcism (a document that would later become integral to Blatty’s writing of the Exorcist novel and subsequent movie). The most prominent book about the case is Possessed: The True Story of an Exorcism by Thomas B. Allen, who reconstructed the events from the diary and interviews with surviving witnesses. See info on more sources at the end of the article.

* * *

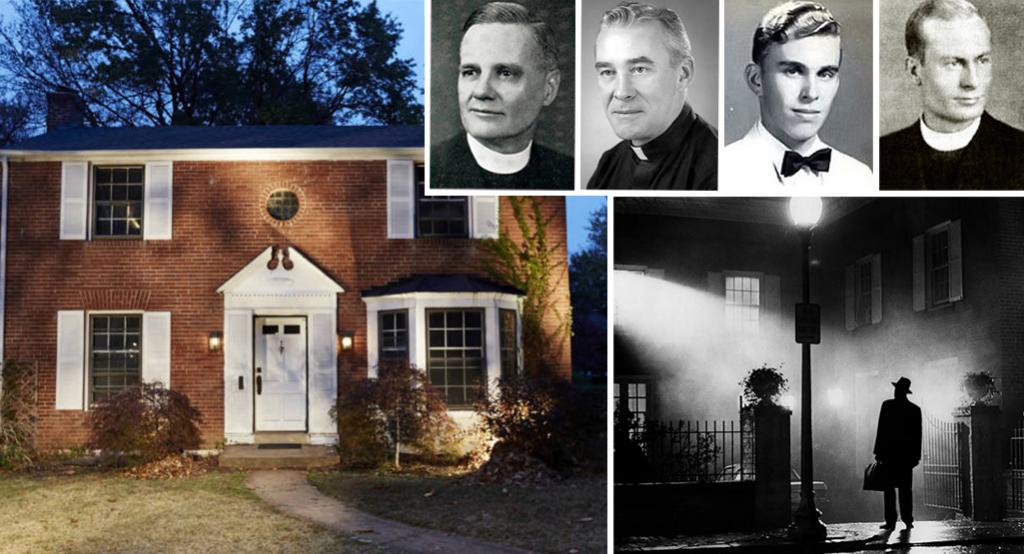

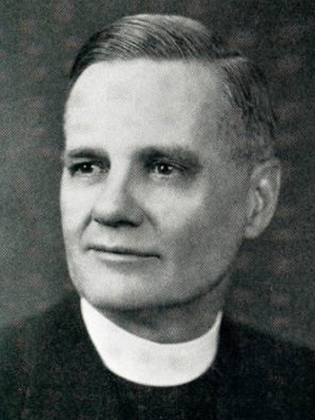

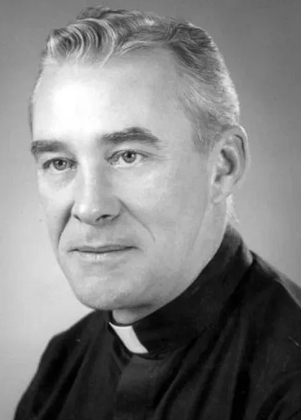

Father Bishop

Rev. Raymond Bishop, SJ, was a Creighton education department professor for over 20 years, from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s.

But before then, he taught at St. Louis University. One day in the spring of 1949, he was approached by one of his students, who told him that her 13-year-old cousin — referred to by the Church with the identity-protecting aliases “Roland Doe” or “Robbie Mannheim” — was being tormented by violent supernatural attacks.

The attacks had begun, the student said, after Robbie’s beloved aunt died. His aunt Tillie was a spiritualist who taught Robbie how to use a Ouija board, and the family believed the trouble started when Robbie used the board to contact Tillie in the afterlife. (In the film, the possessed girl, Regan, also uses a Ouija board.)

By this point, Robbie’s family had already consulted physicians, psychiatrists and their Lutheran minister. They’d taken Robbie to get psychological and physical testing at the Georgetown University Hospital, but no ailments were revealed nor diagnoses made. The family had grown increasingly desperate.

Robbie’s cousin told Fr. Bishop that the strange episodes started a few months prior. Back in the boy’s Maryland home, Robbie and his family had reportedly heard scratching sounds in the walls and beneath the floorboards and seen heavy furniture moving on its own, objects flying across the room and a Crucifix on the wall that shook whenever Robbie was near.

One night, Robbie reportedly went into a trance-like state, and the word “Louis” appeared within a red rash on his ribs. Robbie’s mother took this as a sign that they needed to go to St. Louis and stay with family. While there, they would seek the help of the Church.

Fr. Bishop had no experience with exorcisms, hauntings, possessions or supernatural phenomena of any kind. But he didn’t want to turn away a family in need. He sought advice from St. Louis University President Paul Reinert, SJ, whose brother Carl Reinert, SJ, would become Creighton University President a short time later. Fr. Paul Reinert encouraged Fr. Bishop to bless the suburban St. Louis home where Robbie was staying.

Fr. Bishop later wrote in his diary that when he arrived to meet Robbie, the boy’s bed started shaking, but it stopped when Fr. Bishop sprinkled holy water and made the sign of the cross. Robbie’s body, Fr. Bishop recalled, was covered in scratches.

Father Bowdern

Fr. Bishop believed the boy was possessed by a demon and required an exorcism. He went back to SLU and asked for the assistance of his friend Rev. William Bowdern, SJ.

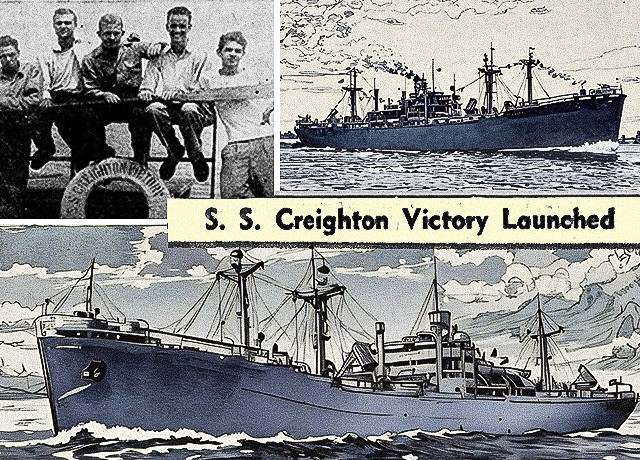

The then-52-year-old William Bowdern was the pastor of SLU’s St. Francis Xavier College Church. He was also the brother of Thomas Bowdern, SJ, who had been the president of Creighton University during the last few years of World War II.

Fr. William Bowdern had served as a chaplain overseas and witnessed all manner of horrors. But, like Bishop, he had no experience with exorcism. To proceed, the two Jesuits would follow “The Rite of Exorcism,” a ritual dating back to 1614.

The Rite was revised in 1999, one of the last reforms post-Vatican II. The new guidelines for exorcism say that "the person who claims to be possessed must be evaluated by doctors to rule out a mental or physical illness." Most reported cases do not require an exorcism because modern Catholic officials regard genuine demonic possession as an extremely rare phenomenon that is easily mistaken for natural mental disturbances.

But in 1949, the Church was still using the Rite. Bishop and Bowdern studied the procedure and were granted permission from the St. Louis Archbishop to perform a formal exorcism on Robbie Mannheim. Bowdern agreed to take the lead.

Father Halloran

This brings us to the third Creighton-connected Jesuit of the story, Rev. Walter Halloran, SJ, who would later help run the University’s Alumni Relations division in the 1980s.

In 1949, Fr. Halloran was a Jesuit scholastic studying history at St. Louis University. He was also Fr. Bowdern's driver.

One night, Bowdern asked Halloran to drive him and Fr. Bishop to a house in the suburbs. When they pulled up to the home, Bowdern leaned over to the front seat and said, “Come on in with us, Walt. I’ll be doing an exorcism. We might need your help.”

Shocked as he was, Halloran didn’t ask questions. He dutifully followed Bishop and Bowdern into that house as they began the first of 20 to 30 exorcism sessions over the next several weeks, taking place at that house, on the St. Louis University campus and at the Alexian Brothers Hospital. Robbie was cared for by physicians and family members throughout the ordeal.

An excerpt from Fr. Bishop’s diary: “March 18, 1949. The prayers of the exorcism were continued, and Robbie was seized violently, so he began to struggle with his pillow and the bed clothing. The contortions revealed physical strength beyond natural power. Robbie spit at the faces of those who prayed over him. He spit at the relics and at the priests' hands. He writhed under the sprinkling of Holy Water. He fought and screamed in a diabolical, high-pitched voice.”

One night, the word “HELL” reportedly appeared on the boy’s chest. (Witnesses claimed his hand had been nowhere near the word.) Another night, Robbie punched Halloran in the face and broke his nose.

The exorcism sessions would always begin in the evening and last well into the next morning. After each endless night, Robbie would return to normal as though coming out of a trance. He told the priests he had no memory of the exorcisms themselves. He would then typically sleep most of the day while the Jesuits returned to their teaching, studies or parish work.

Throughout the exorcism, the Archbishop and SLU president had instructed the Jesuits to be discrete and keep up appearances as though nothing out of the ordinary was happening. The exorcism continued for over a month, and the men were exhausted. Other Jesuits assisted throughout the sessions, but Bowdern and Bishop were the only constants.

‘This isn’t my territory.”

An interesting side note to the real-life exorcism story involves Frank Bubb, a scientist and mathematician at Washington University in St. Louis whom the family called upon to help Robbie around the time the exorcism was taking place.

Dr. Bubb, who had been a key figure in making the first atomic bomb for the Manhattan Project a few years prior, was fascinated by the paranormal and reportedly thought the objects moving around Robbie could be explained by electromagnetism.

According to a later interview with Fr. Halloran, Dr. Bubb came to the house where Robbie was staying, saw the furniture moving on its own, jotted down some notes and said, “This isn’t my territory,” before rushing out the door.

The Last Exorcism

By the evening of April 18, 1949, the Jesuits had been performing exorcisms on Robbie for over a month. This would end up being the last session. Bishop’s diary reports that during this final night, Robbie started speaking in a different male voice than usual, which said:

“Satan! Satan! I am St. Michael, and I command you, Satan, and the other evil spirits to leave the body in the name of Dominus, immediately. Now! NOW! NOW!"

Then Robbie woke up and told the Jesuits: “He’s gone.”

Robbie described a dream he had in which St. Michael the Archangel fought Satan and his demons to free him from their grip. And just like that, the exorcism was over.

The St. Louis Archdiocese issued a formal report on the incident. Copies of Bishop’s diary were filed away. The case was closed.

The Jesuits were told never to speak about the exorcism publicly, and most of them followed these instructions. But 40 other people also knew about Robbie’s ordeal, and few kept quiet.

‘Priest frees boy reported held in devil’s grip’

The national media caught wind of the story after the Lutheran minister who first helped Robbie’s family spoke of the incident at a parapsychology conference.

In August of 1949, the story made the front page of the Washington Post (as Robbie’s family lived in the D.C. area). The headline read, “Priest frees Mt. Rainier boy reported held in devil’s grip.”

In addition to the media coverage, the story became part of the local lore of St. Louis and the D.C. area.

Exorcist novelist and screenwriter William Peter Blatty learned of the tale in the spring of 1950 while attending Georgetown. His source was a professor named Eugene Gallagher, SJ, who told him about the case and the existence of Bishop’s diary.

(Later, at Creighton, Raymond Bishop would teach alongside another Jesuit professor named Eugene Gallagher. Creighton’s Fr. Gallagher was a beloved professor of education known for feeding, caring for and even training a group of campus squirrels. He was not the same Fr. Eugene Gallagher who told a Georgetown student named William Peter Blatty the story of Robbie’s exorcism, sparking an idea that led to a bestselling novel and the ninth biggest movie of all time.)

Years after graduating from Georgetown, Blatty was a successful writer, mostly of comedies like the Pink Panther movie A Shot in the Dark. He wasn’t a horror writer. Yet he couldn’t get the 1949 exorcism out of his head. He knew he had to write a novel and potentially even a movie about it.

While researching the book, Blatty contacted the exorcist himself, Fr. Bowdern. Bowdern told Blatty he couldn’t reveal the details because of his promise to the Archbishop, but he reportedly told Blatty, “I can assure you of one thing: The case in which I was involved was the real thing. I had no doubt about it then, and I have no doubt about it now.”

On Bowdern’s request, Blatty changed the fictional child in his book from a boy to a girl and moved the location entirely to the D.C. area (to protect Robbie’s identity). Published in 1971, The Exorcist stayed on the bestseller list for 54 weeks and led to the 1973 hit movie of the same name.

For the film’s shoot, a Georgetown Jesuit professor who had taught Blatty served as a technical advisor. Many accidents happened during the production, so many that the film’s director, William Friedkin, asked the Jesuit technical advisor to bless the set.

Upon its theatrical release — it came out the day after Christmas, of all days — The Exorcist was instantly notorious. Which, of course, meant people couldn’t stay away. Audiences lined up for blocks and waited for hours to see the movie.

As a ticket-selling gimmick that might have had some truth to it, the film’s marketing team got the media to report on audience members passing out from fright. At many showings of the film, nurses, physicians and ambulances waited in lobbies or outside theaters on standby.

With its unprecedented commercial and critical success, The Exorcist didn’t just inspire the next 50 years of horror movies; it also set the mold for the modern cultural conception of exorcism itself. Our idea of exorcism is inextricably linked to that film, which was itself inextricably linked to that 1949 incident, in which three Creighton-connected Jesuits tried to help a troubled boy.

‘He’s with God now.’

So what became of that boy and those Jesuits?

Fr. William Bowdern returned to his work as pastor of Xavier College Church at St. Louis University. He remained there for some time later. He never performed another exorcism. According to his nephew, he wouldn’t even talk about the incident with family members. Fr. Bowdern died in 1983 at the age of 86.

Shortly after the exorcism. Fr. Raymond Bishop started at Creighton University, where he worked as a professor of education for the next 20 years. He died in 1978 at the age of 72. His diary made the Robbie Mannheim exorcism one of the most extensively documented cases in modern times (and undoubtedly the most publicized).

Fr. Walter Halloran, the Jesuit scholastic who became the exorcist’s assistant, was ordained into the Society of Jesus in 1954. He would teach history and religion at various high schools and universities for years, later serving as a chaplain for a U.S. Army paratrooper unit in the Vietnam War. (He was awarded two Bronze Stars for his service.) He once told a reporter that he saw more evil in Vietnam than he did in Robbie Mannheim’s hospital bed.

Though Fr. Bowdern didn’t doubt that Robbie had experienced demonic possession, Fr. Halloran wasn’t so sure. Once asked to go on record saying whether he thought the boy was possessed, Halloran said, “No, I can’t go on record. I never made an absolute statement about the thing because I didn’t feel I was qualified.”

In the late 1980s, Fr. Halloran was named assistant director of alumni relations at Creighton University. He died in 2005, the last surviving member of the exorcism team.

And what of the boy, Robbie Mannheim? His true identity was revealed in 2021, about a year after his death at the age of 86. (We won’t reveal his full name here, but you can find it online easily enough. His real first name was Ron.)

Ron had no known recurrence of the phenomena that marked those months in 1949, and he went on to live a normal life. Better than normal, in fact.

He became a NASA engineer and patented space shuttle panels capable of withstanding extreme heat. His work made possible the Apollo space missions of the 1960s that led to the moon landing.

Other stray details about Ron — reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch — are apocryphal at best: that he lived in Omaha, that he named his first child Michael, after the archangel who saved him.

Shortly after Ron’s death, the New York Post interviewed his former companion, who remained anonymous. She said Ron spent his life terrified that his NASA colleagues would find out he was “the exorcist boy.”

“On Halloween, we always left the house because Ron figured someone would come to his residence and know where he lived and never let him have peace.”

His companion also revealed that Ron himself didn’t believe he was ever demonically possessed.

“He said he wasn’t possessed, that it was all concocted. He said, ‘I was just a bad boy.’”

In this same New York Post story, the woman said that shortly before Ron died, a Catholic priest showed up on their doorstep to perform last rites. She was baffled. No one had called the priest.

“I have no idea how the Father knew to come,” she said. “But he got Ron to heaven. Ron’s in heaven, and he’s with God now.”

Other sources:

SLU Legends and Lore: The 1949 St. Louis Exorcism

Exorcism Expose, St. Louis University

“The Haunted Boy” by Strange Magazine

The St. Louis Exorcism of 1949, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“The Real Story Behind The Exorcist: A Q&A with Henry Ansgar Kelly”

* * *

You can listen to our podcast episode about Creighton's connection to the exorcism here.