Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

Women should be interested in world problems as well as men. The world is their world.

By Jon Nyatawa

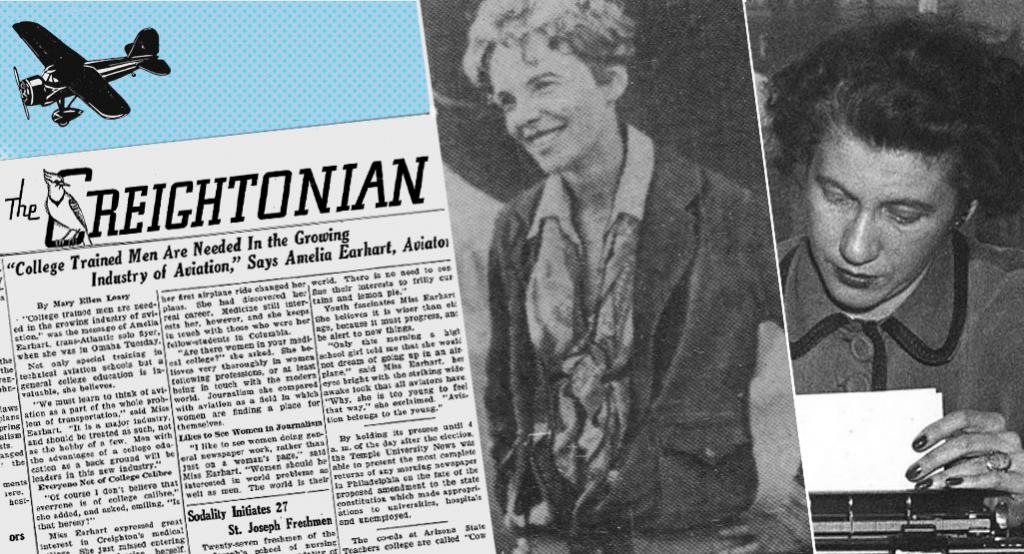

About a year after Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean, as her stardom and prestige soared to new heights, she landed in Omaha for a speaking trip. And Earhart shared a few moments with a Creightonian reporter.

It was Dec. 12, 1933. Ninety years ago.

Women’s rights were on the mind of Earhart, a staunch advocate for equality. So, when Earhart learned about the nearby university, she wondered aloud.

“Are there women in your medical college?” Earhart asked Creightonian reporter Mary Ellen Leary Sherry, BA’34.

In Sherry’s account for the Creightonian, she wrote that Earhart considered a college education to be “invaluable.” And after “Miss Earhart expressed great interest in Creighton’s medical college,” the record-setting aviator noted the importance of women “following professions, or at least being in touch with the modern world,” Sherry wrote.

Earhart, who disappeared during a flight in 1937, proved to be exceptional because she didn’t accept society’s boundaries for women. She flew faster, higher, further. And she believed all women could do the same, whether they dreamed of following her career path as a pilot or found their own calling as doctors, lawyers, inventors, educators … and journalists.

Perhaps a bit of Earhart’s ambition rubbed off on Sherry that day.

Or maybe Sherry was simply extraordinary, too, in her own way.

(For the record, the answer to Earhart’s question about Creighton was: “Yes!” The first female student in Creighton’s medical school, Kate Drake, enrolled 41 years earlier in 1892 – she was also the first woman admitted to any Jesuit university in the U.S. Additionally, Anna Marie Griffith, MD’1898, became the first woman to graduate from Creighton and complete all medical school training.)

From one trailblazer to another

In an extensive interview in 1990 with the Washington Press Club Foundation for its “Women in Journalism” project, Sherry never mentioned her brief encounter with Earhart.

But Earhart, at least on that 1933 day in Omaha, did seem impressed by Sherry’s pursuit of a journalism career. Earhart said in the Creightonian article that “women should be interested in world problems as well as men. The world is their world.”

Sherry very much lived that way. And she got her start at Creighton.

Sherry said in the 1990 interview that she “did not feel on the outside” at Creighton. She and the male journalism students had a shared interest – “it was fine,” she said. But still, she was the only woman in her journalism classes. She wrote for the Creightonian and helped produce the university yearbook, among other things.

She technically was enrolled at Duchesne College, an affiliate of Creighton. She said she walked “10 to 12” blocks down California Street each day to attend class. She worked late and sometimes missed dinner at home to assist with writing, editing and publishing.

“As women, we were expected to be growing up to get married and have children and run a household, and very few people expected us to be interested in talking about business or world affairs or things of that kind,” Sherry said in 1990.

Sherry was different, though. A pioneer. Her career accomplishments in journalism speak for themselves.

She began as a secretary, quickly earned her stripes and eventually wrote about social welfare, urban development and politics for the San Francisco News. The first year that Harvard University started accepting women to its Nieman Fellowship in 1946, Sherry was one of two who earned a spot. She was among the first women to ever cover the California statehouse. She authored the book “Phantom Politics.” She also wrote for Scripps-Howard News Service and The Economist in London.

In Sherry’s obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle, the newspaper reported that early in Sherry’s career, she was prohibited from joining the San Francisco Press Club and couldn’t attend the Capitol Press Association’s annual dinner at the governor’s mansion.

But she kept pushing and working until the barriers came down. Sherry died in 2008.

“I have to confess that I never thought of myself as a feminist,” Sherry said in 1990. “I never consciously thought, ‘I'm doing this for other women.’ I strongly felt, ‘I can do as well as any man. And I can use my head as well and I can work as hard as any man, and I'll show 'em.’ But looking at some stages, I thought, well, at least by doing it as well as any man, I showed that women can.”