Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

We have 14,000 patients and more than 40,000 encounters annually. Many of those patients are older and have multiple medical problems, and the clinic becomes an ambulatory center that provides not just opportunities for dental care but for all health professions.

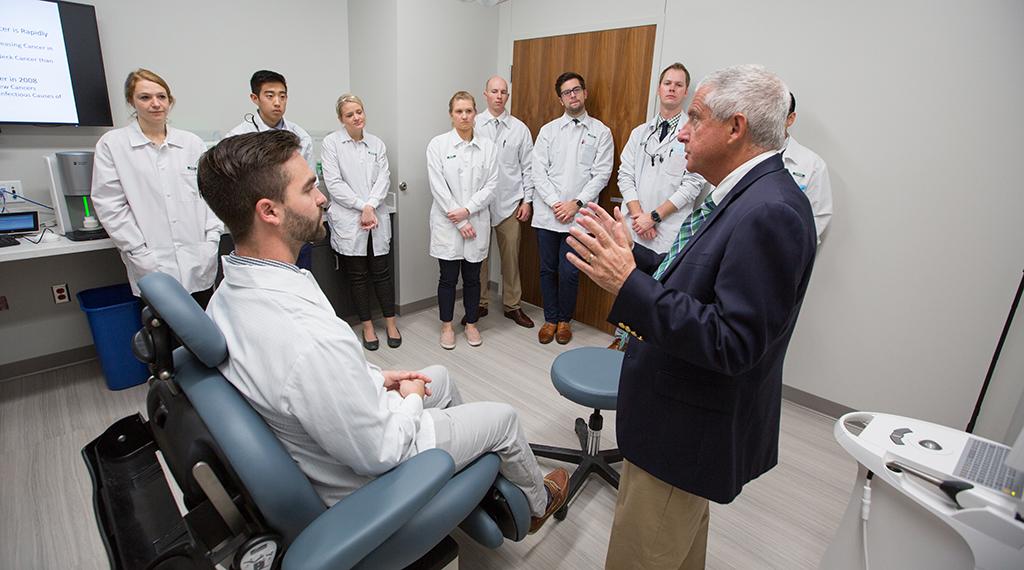

A physician walks into a dental school … The physician — head and neck cancer surgeon Thomas Dobleman, MD — is showing Creighton dental students how to spot malignancies from clavicle to cranium.

His mock patient — fourth-year dental student Robert Wollschlager, BS’14, MS’16 — sits in the exam chair.

Dobleman’s hands race around Wollschlager’s neck, face and jawline as the physician tells the class, “If you were doing an exam, you would feel the carotid, then the submandibular glands, the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle — that’s where the jugular vein is and where a lot of lymph nodes develop.”

Dobleman’s hands are still moving …

“Then we feel posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the trapezius, the supraclavicular area, then I’ll feel your thyroid, OK, swallow.”

Wollschlager swallows. Dobleman turns back to the class.

“What did that take? Eight seconds? If you guys can do that with your patients, you’re going to find head and neck cancers, skin cancers and lymphomas, and you’re going to save a lot of lives.”

Dobleman’s head and neck clinic for fourth-year dental students and medical students is one of the interprofessional education activities currently offered by the School of Dentistry. Spearheaded by Creighton’s Center for Interprofessional Practice, Education and Research (CIPER), the courses bring in health professionals of various disciplines to work together for the education of the students and the sake of the patients.

The curriculum is part of the University-wide effort to integrate collaborative care into all health professions.

What is collaborative care?

It’s a model that breaks down the silos, that brings everyone together, that draws upon all disciplines for the betterment of the patient. Studies, including one conducted at CHI Health Creighton University Medical Center–University Campus, have shown that the model lowers costs and improves outcomes for patients.

The idea is this: Collaborative care is the best way to treat the whole person (something Creighton knows a thing or two about).

For the School of Dentistry, this means expanding education and treatment far beyond the scope of the mouth.

“When it comes to different health professions learning together, the dental school offers a great opportunity for everyone to work in a clinical setting,” says Dean Mark Latta, DMD, MS. “We have 14,000 patients and up to 50,000 encounters annually. Many of those patients are older and have multiple medical problems, and the clinic becomes an ambulatory center that provides not just opportunities for dental care but for all health professions.”

Many of the dental school’s patients, Latta says, go to the dentist more than they go to the doctor. This puts dentists on the front line of health care, meaning they need to know how to look for more than oral disease. A patient who comes in with a toothache is also getting looked at for hypertension, diabetes and, as mentioned, head and neck cancers.

Creighton students aren’t just embracing this team-based approach, says Joseph Franco Jr., BA’80, DDS’84, assistant dean for clinics and chief dental officer. They’re helping drive it.

“We can learn from everybody, and we can certainly learn from our students,” Franco says. “As they treat patients, they’re letting us know where we have gaps and how to fill them.”

Even when those gaps aren’t strictly related to health care — let alone dentistry.

Dental students were the first to note that many patients were having trouble getting to the clinic. The dental school has since brought in a social worker to help patients address transportation needs and other issues. Franco says this has added a whole new level of care to the clinic.

There remain obstacles to such team-based care, of course.

For one, the insurance model hasn’t yet caught up to it. Providers, including dentists, are still often paid on a procedure-by-procedure basis. Collaborative care would be better matched with a value-based pay model, which reimburses providers for overall health outcomes.

Health care isn’t there yet. But if fee-for-service remains the norm for now, insurers are increasingly moving toward an outcomes-based future.

Other obstacles include ego, tradition, any and all other elements of inertia that can work against this type of sea change.

“There’s resistance in all professions because of the fear of losing control or losing status,” Latta says. “Team-based care might be perceived as being a flattening of a hierarchy, but the reality is each of the professions has a distinct and important role. What we’re trying to do is reorient our education to be patient-centered. And if you’re focusing on what’s best for the patient, hierarchy shouldn’t matter.”

One of the great things about being at a Jesuit school, Latta says, is that “when we face obstacles, our values help us keep our energy up and motivate us to put in the extra effort to make things work.”

The dental school already has plenty of working examples of what collaborative care looks like — for instance, Creighton pharmacy students offering medication therapy management on the clinic floor.

Assistant professor Kalin Johnson, PharmD’12, BSHS’12, serves as the dental school’s on-site pharmacist. She and her students work with patients to manage medications and with dentists to evaluate how those medications might affect treatment. Some meds, for example, have the side effect of dry mouth. Others prolong bleeding time.

“Dental pain might be the thing that gets patients into the clinic, but we’re going to be there to help with other needs they might have,” Johnson says. “There are a lot of opportunities here for all health professions to make an impact.”

That impact is cumulative — because when Creighton students work together for the good of the patient, they are, in fact, learning how to work together for the good of the patient.

That’s an essential skill they take with them wherever they go.

“We’re all learning what it takes for everyone to work together,” says resident assistant professor Teryn Sedillo, DDS’14.

Sedillo established an annual clinical training experience in which Creighton occupational therapy and dental students work on proper transfer and accommodation for patients with limited mobility. “The goal,” she says, “is to maximize the safety and comfort of the patient and provider.”

It all starts in class. It all starts with relationships.

In his head and neck clinic, Dobleman gives this advice: “Don’t just hang around other dentists.

“Likewise, I tell medical students, ‘Don’t just hang around other physicians.’ Make friends with other health professionals. That way you’ll grow together and learn together, and it’s going to be great for the patient. That’s what this is all about.”

Once he’s done serving as Dobleman’s mock patient, Wollschlager talks about how much he’s learned as a Creighton dental student.

“When I graduate, I’m going to know what to look for,” he says. “And it’s not just looking at teeth. It’s looking at everything, treating everything.”

Treating each part of the whole person — including (ideally) the smile on their face.