Featured Testimonial About Creighton University

Creighton was the fertile ground where I could plant some real seed for who I wanted to be in the world.

Kyle Korver was an NBA rookie in 2004 living out his dream. Enjoying success, money, fame and adoration. He was 23, and he'd made it!

And yet ...

“I wasn't full, and I knew it,” Korver said. “And the only reason I knew it is because I had watched people at Creighton, when I had gone through my formative years — people who didn't have these things that I have, but they were more solid in who they were and what they were going to be about. They knew it is not what you are, it's who you are.”

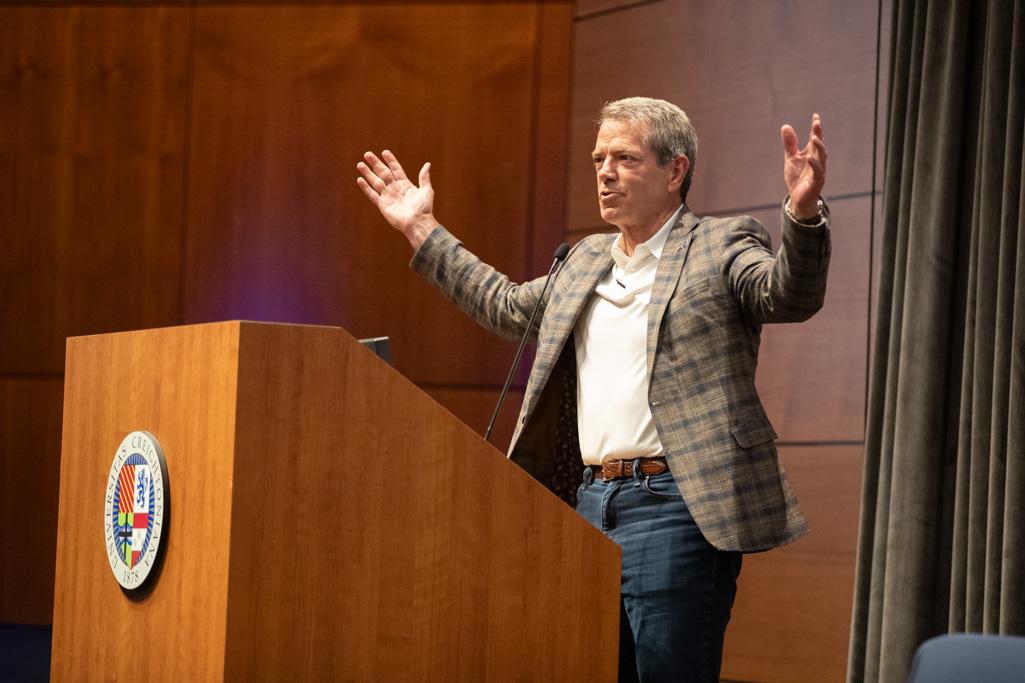

Korver, BA’03, reflected on his time at Creighton — when he starred as an All-American basketball player but also solidified his own set of foundational values that would guide him in life — at the 2024 Sport at the Service of Humanity Conference recently hosted at the Harper Center.

Korver is now an assistant general manager with the Atlanta Hawks after ending his 17-year NBA playing career in 2021. He’s one of the league’s best long-range shooters ever, ranking in the NBA’s top 10 in most career 3-pointers made and best career 3-point percentage. He’s also sixth on Creighton’s all-time scoring list.

But as emphasized by the pillars and themes of the Sport at the Service of Humanity Conference, Korver’s fulfillment and self-worth are not defined by his achievements on the court.

Basketball is part of Korver’s story — but it’s not THE story. At Creighton, Korver said, he began figuring that out.

“Creighton was the fertile ground where I could plant some real seed for who I wanted to be in the world,” Korver said. “Because really, when you leave your house and you leave your parents and you're off on your own, you’re kind of for the first time putting some seed down — like, 'This is who I'm going to try to be for the next few decades.’ And to have the leadership and the wisdom that comes along with the Jesuit heritage was so formational for me.”

To learn more about the three-day Sport at the Service of Humanity Conference, a series that originated at The Vatican in 2016, follow this link. To see additional photos from the conference, scroll down.

Highlights from Korver’s conversation

Korver discusses the intersection of faith and sports, and the ways athletic pursuits can expose flaws and inspire growth. The following questions and responses have been edited for clarity.

When did you recognize that your ambition to succeed as a basketball player wasn’t the only force driving you to be your best self?

“Obviously, it takes time to figure those things out. I think that's where being in a place like Creighton, being able to have experiences with people around you that can help process your moments to turn the moments into wisdom, that's what matters.

“Someone can't just tell you this and then you get it, and you start living. You need to have a space where you can figure things out on your own. Where you can run, and you can trip, and you can fall. Having a space and having people around you who can help you navigate those years is so important.

“There's a countless list of Jesuits and teachers and leaders and coaches who were legs under my table as I was trying to figure this out.”

As an elite athlete competing at the highest level, where do you build in time to think about inclusion, involvement, perhaps social commitment?

“My grandpa was a pastor who used to say to me all the time when I was young, ‘Kyle, you are blessed, but you're blessed to be a blessing.’ We are all blessed in so many ways, but the reality is, you don't get the full gift of the blessing until you use it for other people, with other people.

“That’s when life gets a little more fun. There's a time and place for a healthy ego to build and to go for things and to work for things. But then at some point, you realize life's not about you anymore. It's meant to be shared. These good things that you've work for, how do you pass it on to the next generation or to the people around you?”

At some point in your NBA career, you realized you could do more. Tell us about the essay you wrote for The Players Tribune in 2019.

“It was in that moment where it's like, ‘OK, I have tried my whole life to be a kind person, to treat people with respect, but I'm not sure I've actually tried to be helpful. What would that look like?’ And so, the whole purpose of that article is, you can't just tell people what to do anymore. You can't just create an argument that is better than theirs and win. But you can call out something in your own life, and you can be honest with yourself and recognize maybe you haven't always known it all or been aware. You can admit that and state how you're going to try to be better going forward and then try to walk that out. That is kind of the only thing that I have found that works.

“There's a line that I've held onto pretty tightly the last four or five years: The best criticism of the bad is the practice of the better.

“You can't just tell people they're wrong. You have to try to admit where you've been wrong and then walk out something different. If it is better, people are going to look at it and be like, ‘Oh, that's good. I think that's right.’ And then they jump on board and conversations happen. Things can start to shift.”

In athletics, there’s the will to win, the need to win. How do you keep that from overriding everything else?

“It is aligning what your true value is. You're going to make a certain set of decisions. And you can see yourself as, ‘I'm going to try to use my craft to leave the world a little better than I found it,’ — which, ironically, was the motto that James Naismith lived by when he created basketball. He didn't think about the trillions of dollars that were going to be tied to this game. His motto was, leave it a little better than when he found it.

“I think that's really the posture that I'm trying to bring to the work that I'm in. It's easy to just say, ‘Hey, I'm trying to win in life and build my own brand and take care of my family.’ Or, do you want to try to be a part of bigger stories? And it's hard to do because you don't always win right away. But ultimately the goal is to leave it a little bit better than you found it and try to participate in the really complicated and hard stories that are going on in this world.”

“Live like you play” is a central tenant for Sport at the Service of Humanity. What does that mean to you?

“I think when you're playing, you are putting your whole creative, playful, excited self into the mix. I've always felt that was when I was the best version of myself as a basketball player, when there wasn't the pressure to get it right. I love this game. I love competing. I love the bump and the grind. I love when things get hard. I like it when the ball goes in the basket. It’s really just letting your authentic, true self shine through.

“I know that we all come with warts and different things, but I do believe in the good of humanity. The most beautiful thing in all of humanity is when humans use their good strengths and their natural, authentic selves to honor and create for other people. When you watch humans lock arms with a pure posture towards the good work, it is amazing what we can do.”

***

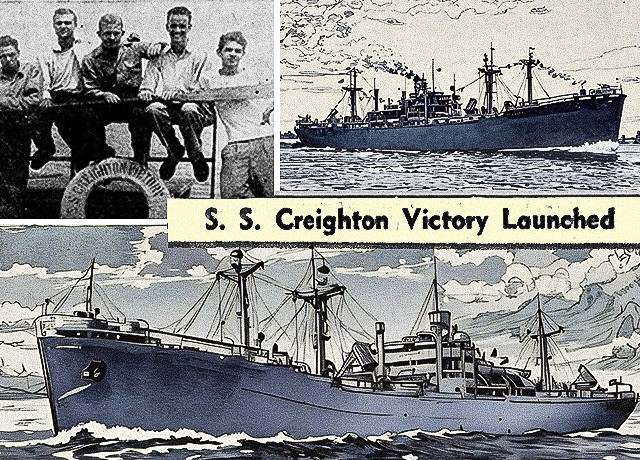

2024 Sport at the Service of Humanity Conference